By Carla Crowder, Executive Director

Carla.Crowder@alabamaappleseed.org

One year ago, Alvin Kennard stood in a Bessemer courtroom nervous and uncertain. Striped jailhouse scrubs swallowed his rail-thin, shivering frame. After 36 years in a sweltering, unairconditioned prison, the chilled air of Judge David Carpenter’s courtroom was a shock to his system.

What came next was a shock to the justice system. In 1983, Mr. Kennard had been sentenced to life without parole for a $50 robbery at a bakery. Judge Carpenter scrapped that and resentenced him to time served. A courtroom filled with Mr. Kennard’s friends and family erupted in hallelujahs. The television cameras started rolling. As his attorney, and a worrier by nature, I immediately started thinking about next steps: This 58-year-old man had been incarcerated nearly two-thirds of his life. How on earth was he going to adjust to the outside world?

Extremely well, it turned out. Alvin Kennard filed a tax return this year. He tithes at church. He hasn’t even been affected by Covid-19, other than limits on the family gatherings he loves.

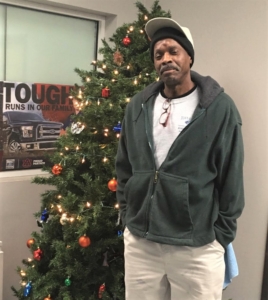

Alvin Kennard outside his home in Bessemer. August 28 marks the year anniversary of his freedom from a sentence of Life Without Parole for a $50 robbery. By Bernard Troncale

Mr. Kennard’s large, supportive family was critical to his successful re-entry. A room was ready in his brother’s home. A niece, who is a Bessemer businessowner, helped with transportation. Church connections helped him secure employment within six weeks at Town and Country Ford, where he works in the body shop buffing cars. Every so often, he calls me on his lunch break and lets me know things are still going just fine. During the holidays, he texted me photos of him at the staff holiday party, standing next to a huge inflatable polar bear. Imagine returning from Alabama’s hellish prisons to a world where holidays are filled with enormous glowing inflatables. Mr. Kennard embraces it all – with joy.

“It’s almost a year I’ve had my job,” he remarked recently. “It’s been a blessing, it’s been wonderful. It’s not about how much money I’m making, it’s about what God allowed me to do.”

He loves listening to the birds chatter in the mornings, wandering down to the creek of his childhood and watching turtles and snakes. He’s got a favorite meat-and-three restaurant, Kayla’s, that’s helped him put on much-needed weight.

Mr. Kennard at work over the holidays. He’s employed in the body shop at a Ford dealership in Bessemer.

All conversations with Alvin Kennard eventually lead toward God. No matter how hard I try to give him credit for how hard he worked, how much he suffered, how he deserves a good life, he invokes God and the conversation becomes a prayer.

I wish more Alabama legislators, judges, and prosecutors could pray with Mr. Kennard.

Until last year, he was labeled a “violent felon” based on his robbery conviction at age 22. Because of three minor non-violent convictions stemming from the same arrest at age 18, he was labeled a habitual offender. Based on the calls and mail that poured into Alabama Appleseed’s office following news of Mr. Kennard’s freedom, there is a world out there that does not see him as a violent felon. “A few month ago, I heard about you. My father was from Alabama, Bessemer, too,” wrote Elizabeth, from Spokane, Washington, who mailed him a little cash – “a gift, so that your days moving forward are hopeful, full of love and belonging.”

Elizabeth acknowledged something else about Mr. Kennard’s story: “I’m learning more about how horrible the police and jail systems are (& the laws, too). It’s not new … but the depth of the corrupt mission is being seen.”

At Appleseed, we’ve also gotten mail from those still stranded in prison honor dorms. Men in their 60s, 70s, one who is 86, sentenced to die in prison for the sins of their youth under Alabama’s draconian Habitual Felony Offender Law. They tell us about their kidney problems, their high blood pressure, their crack-cocaine addictions from the 1980s that led to convenience-store hold ups and courthouse decisions that they were forever beyond redemption. Except now, they are the prisons’ hospice workers, GED teachers, barbers, launderers, preachers, peacemakers, and clean-up crew. “The [whole] time I’ve been in, I’ve worked as a hall runner, shift office runner, infirmary runner and have seen so much brutal violence and had to clean up so much blood out of cells, off of walls and hallways and had to help pick up dead inmates or seem dead and get them to the infirmary,” wrote one man whose conviction dates back to the first Bush Presidency. “I’ve had so much prison blood on my hands, I see it in my sleep.”

Due to the limitations and complexities of Alabama criminal procedure, there is currently no clear vehicle for second chances for these old men in the honor dorms. Mr. Kennard is free only through extraordinary mercy and grace from Judge Carpenter and the Bessemer Cutoff District Attorney’s Office led by Lynneice Washington.

Mr. Kennard turns 60 this year. He will celebrate a full year of employment and get a week’s paid vacation. Most likely he’ll purchase a new suit or two. If there’s one thing I’ve learned about Mr. Kennard this year – beyond his faith and his work ethic – is that he is a sharp dresser, which makes it all the more unfortunate that the cameras were rolling on him while he wore faded jailhouse scrubs.

He is much more himself in his Sunday best.

Alvin Kennard rarely speaks of his freedom without acknowledging his faith in God. By Bernard Troncale