By Eddie Burkhalter, Appleseed Researcher

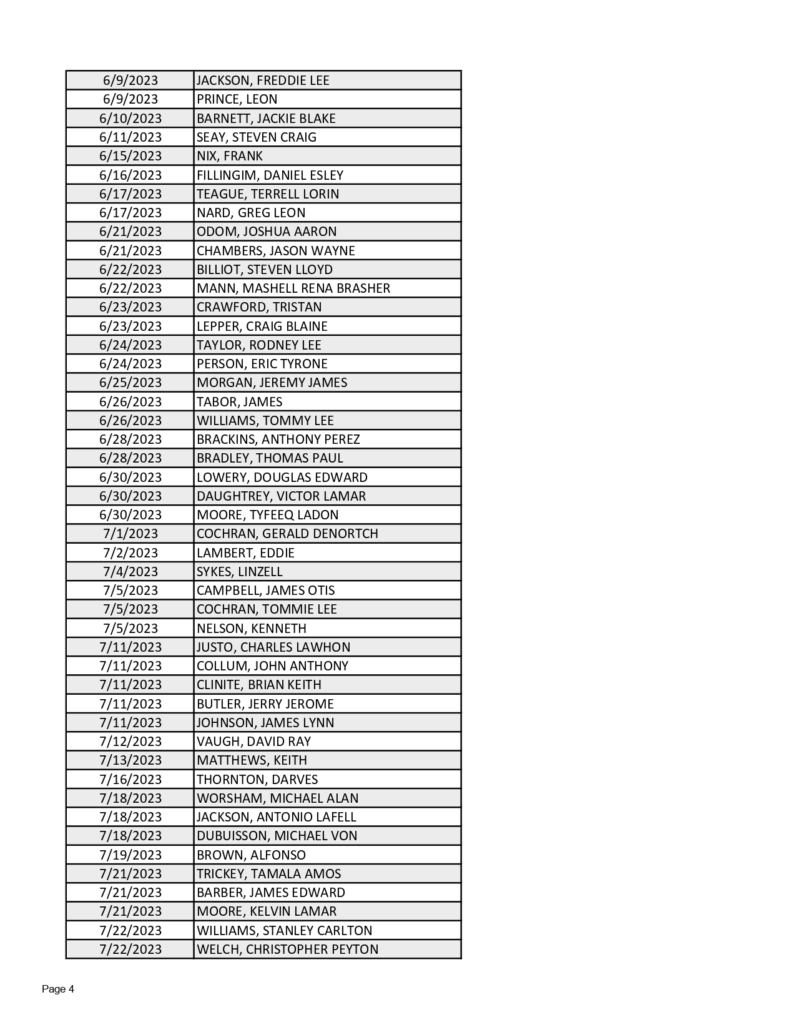

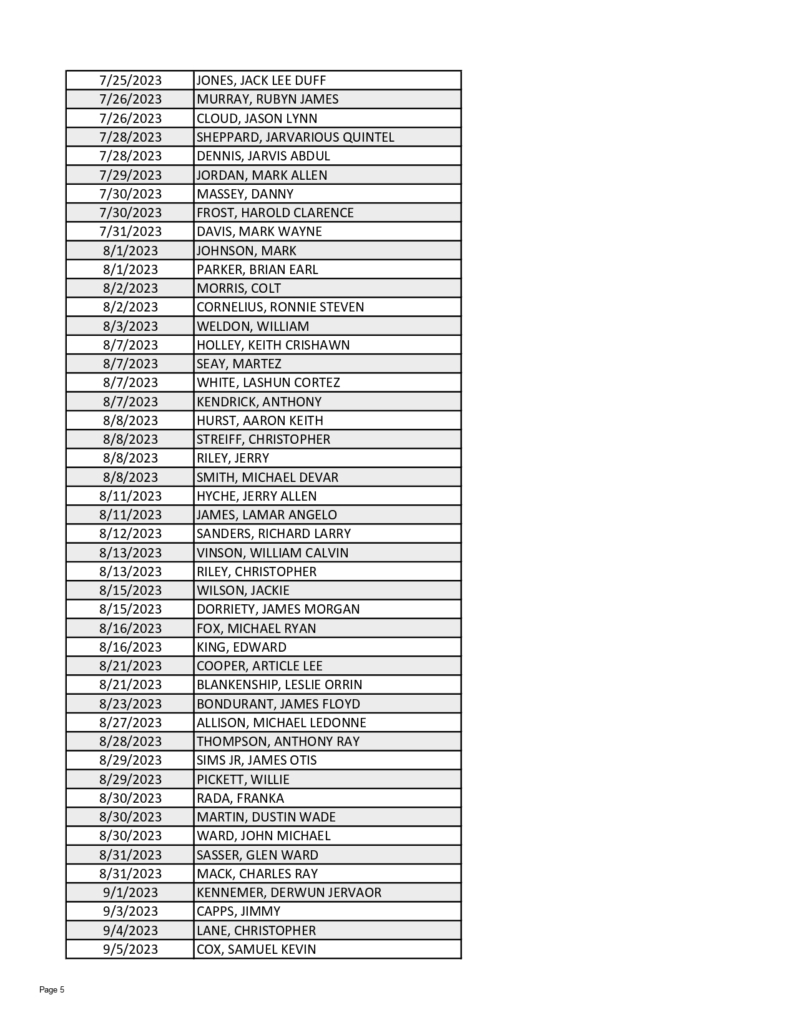

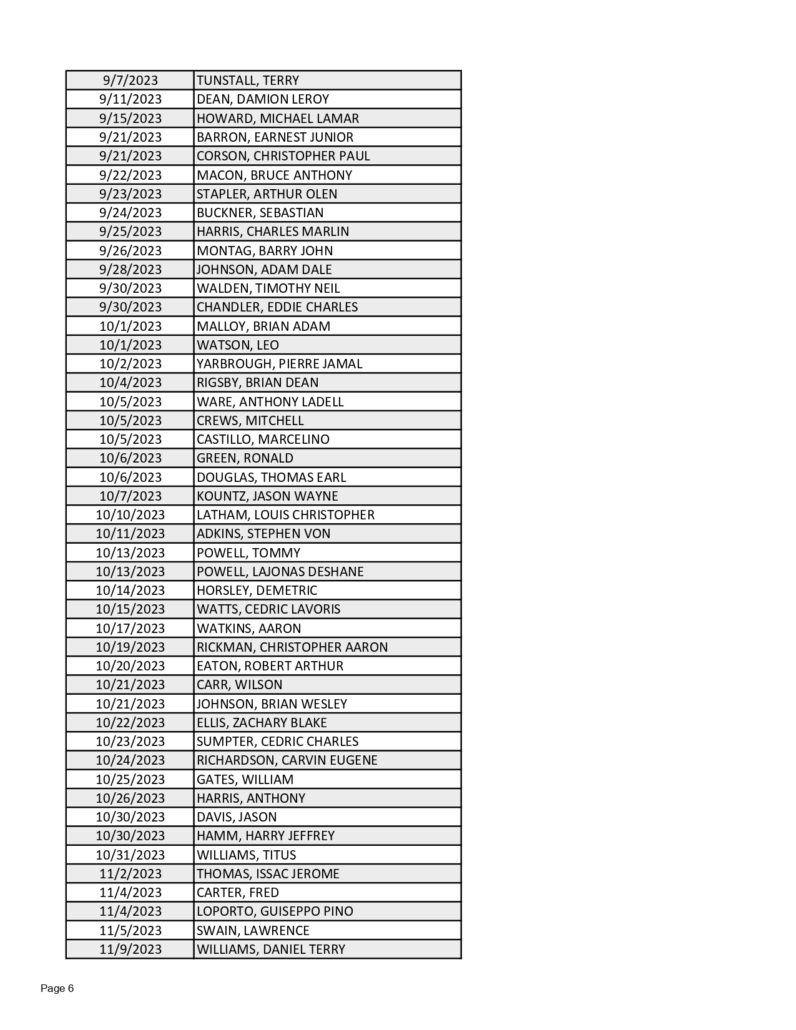

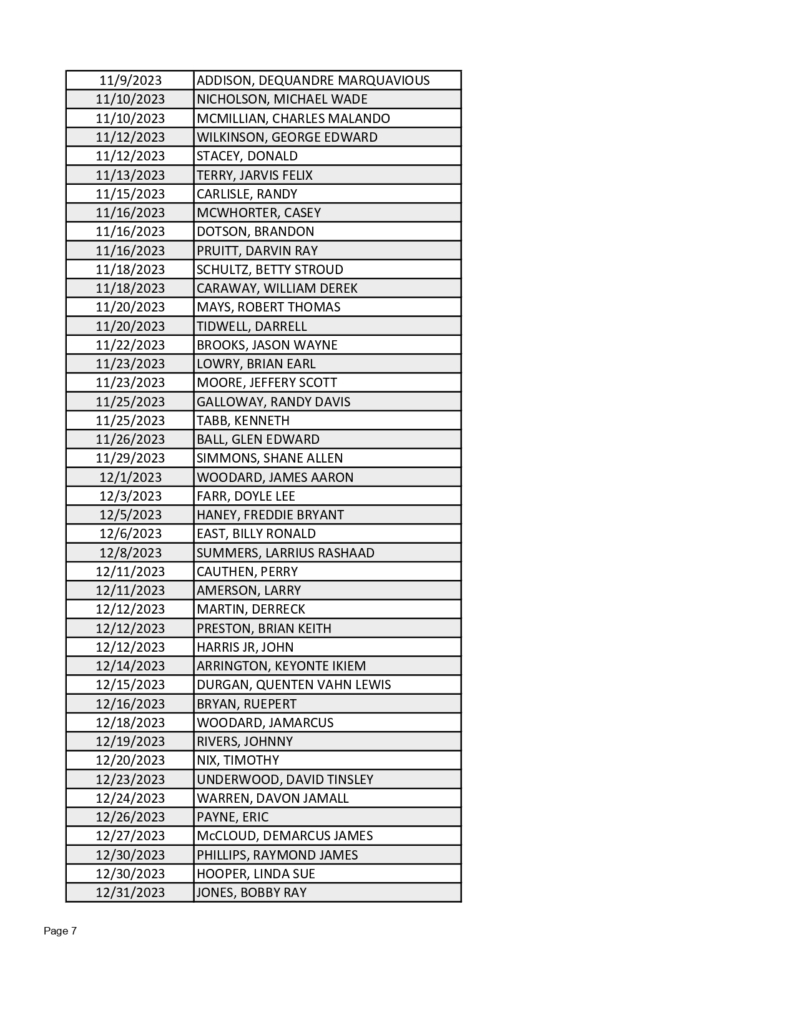

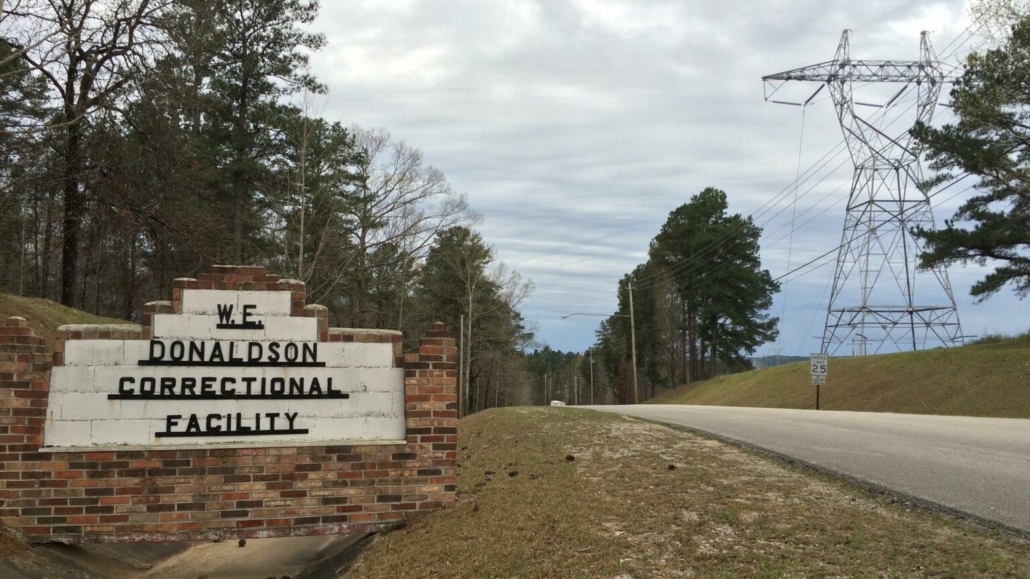

It was five years ago today that the U.S. Department of Justice released a report detailing violations of the U.S. Constitution’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment for incarcerated men in Alabama prisons, and since then more than 1,000 people have died in state prison custody.

The Alabama Legislature’s Joint Prison Oversight Committee meets today and is tasked with providing critical oversight of a department that for decades has been steeped in mismanagement, chaos, corruption, and violence.

The DOJ issued a second report in July 2020 detailing widespread use of excessive force, including deadly force, by corrections officers against incarcerated people, and in December 2020 the DOJ sued the state and the Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC). The trial, which will be closely watched across the nation, is set for November, but could be pushed back.

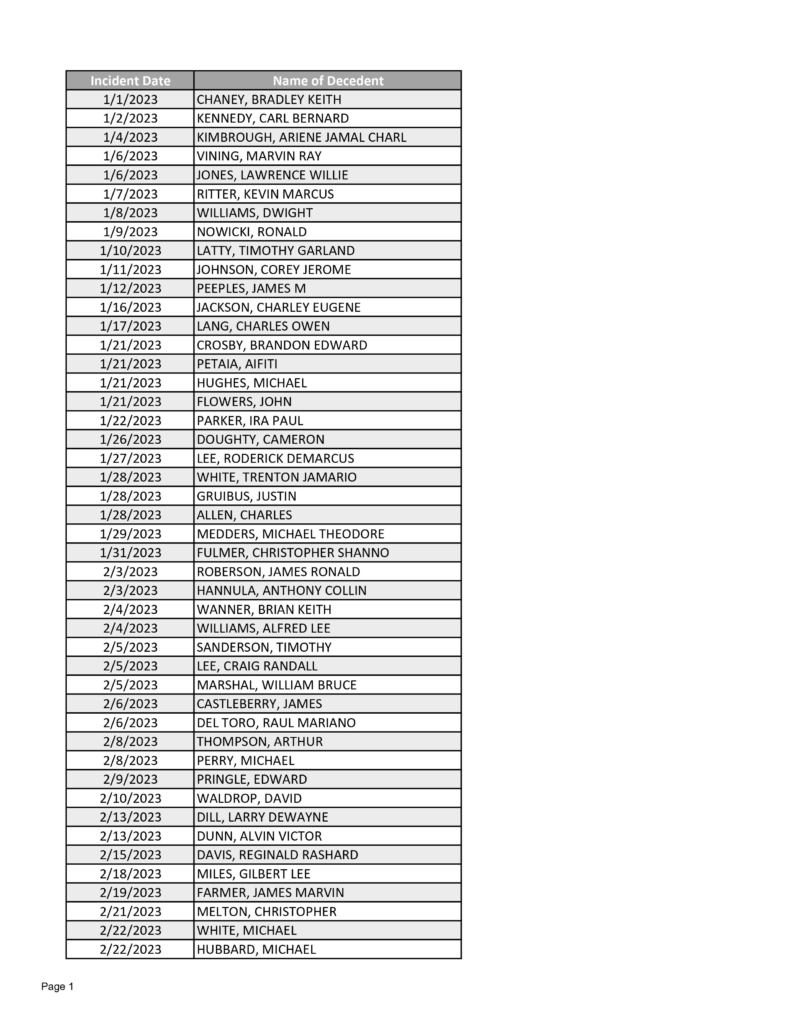

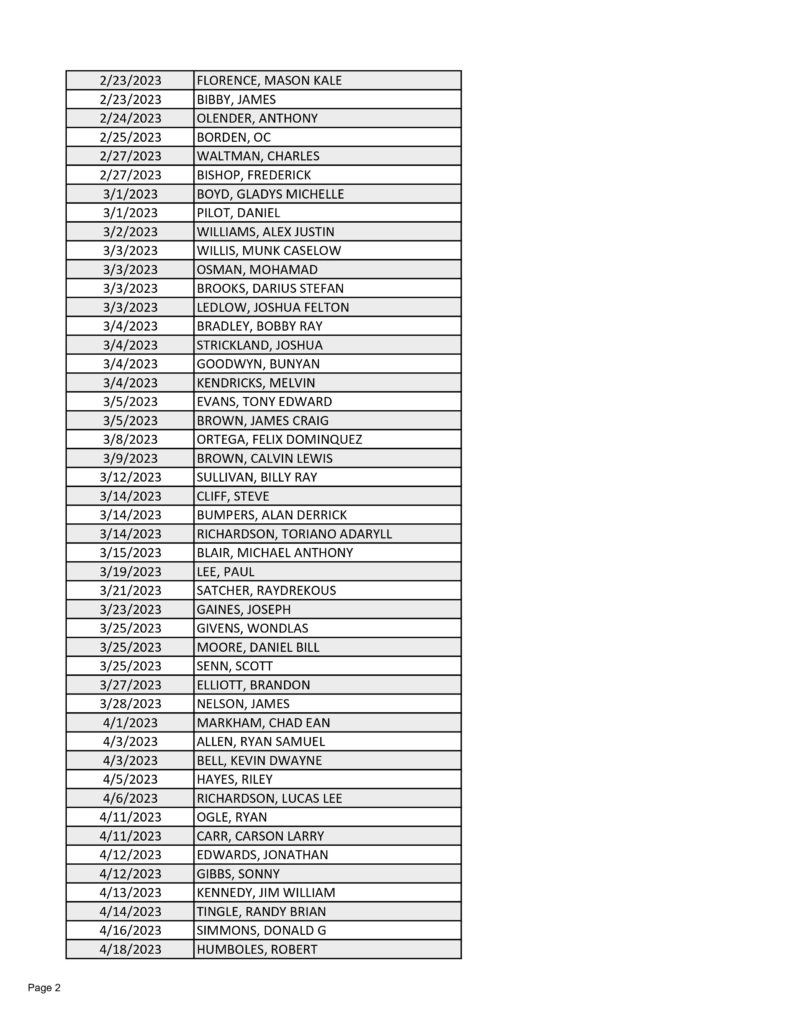

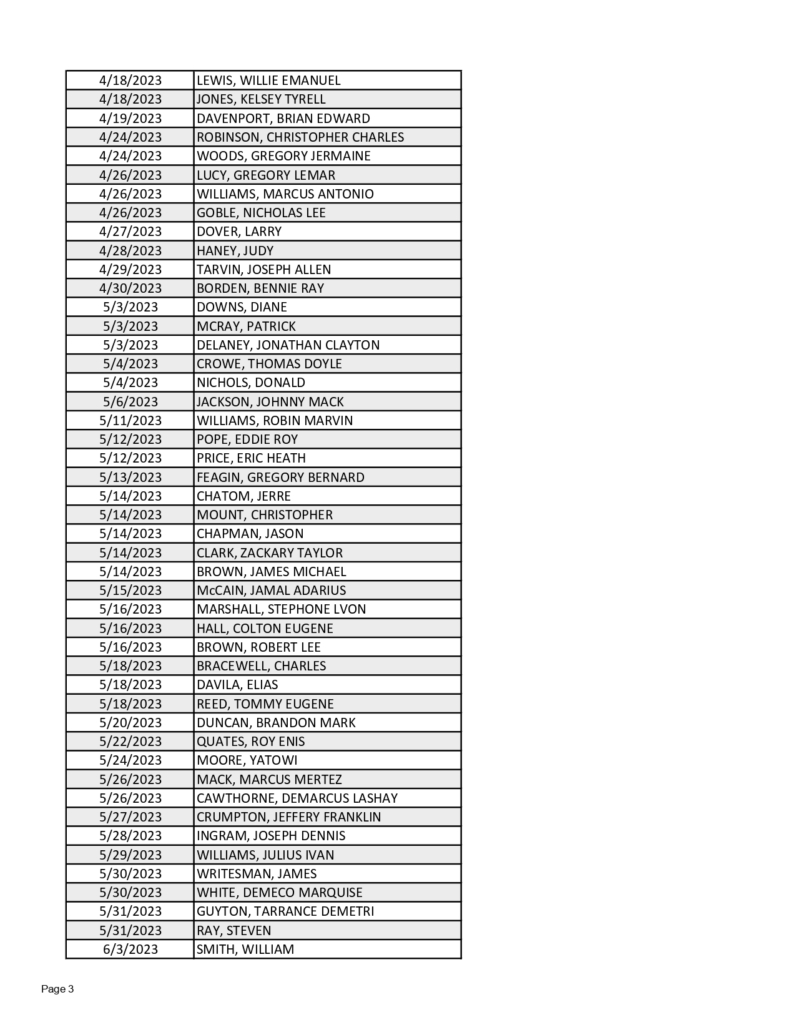

Throughout the last five years, state officials have provided major pay increases to prison guards, increased the ADOC’s budget by 48%, and signed a medical care contract for $1 billion. ADOC officers confiscate hundreds of weapons, even guns, along with enormous amounts of drugs on a regular basis. But nothing seems to stop the carnage. Alabama prisons have a death rate five times the national average, and 2023 saw record loss of life, with 325 incarcerated people dying in state prisons.

Low prison staffing levels were flagged in that first DOJ report as being a catalyst of the violence, yet from December 2017 until Sept. 30, 2020, the state showed an increase of just 25 officers over nearly two years, which was less than 1.5 percent of a judge’s order to add 2,000 correctional officers by February 2022, and the staffing problem has only worsened. ADOC’s quarterly reports show total security staffing fell from 2,102 in December 2021 to 1,763 by September 2023, even after massive recruiting efforts, pay raises and incentives.

And many officers are part of the problem. Between 2018 and the end of 2023, ADOC fired 366 Corrections staff, and more quit before being terminated. During those years 134 ADOC officers and staff were charged with work-related crimes, Appleseed discovered through a records request, with charges ranging from promoting prison contraband to murder.

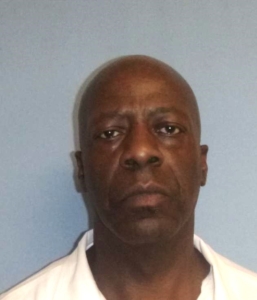

In a recent case, ADOC Sgt. Demarcus Sanders in July 2023 was charged with murder in the death of Rubyn James Murray, 38, beaten to death at the hands of two other incarcerated men, directed to do so by Sanders, court records allege. Those two incarcerated men are also charged with murder. “The defendant confessed to the offense,” an ADOC investigator wrote of Sanders in a deposition.

One of the last men to die in Alabama prisons was 39-year-old Samuel Ward, who was stabbed to death on March 27 by another incarcerated man at Limestone Correctional Facility. It was the fifth homicide at that prison since May 2021, and the second during the month of March.

Gov Kay Ivey and supporters of her plan to build new prisons have said those buildings are the answer to Alabama’s deadly prison crisis, and while lawmakers have secured the money to build the first $1.08 billion prison – in part with $400 in federal COVID-relief funds, and potentially $100 million from state education funds, money for a second planned prison hasn’t been found.

Immediately, after the 2019 report was released, Ivey began promising an “Alabama solution” to the problem. “Over the coming months, my Administration will be working closely with DOJ to ensure that our mutual concerns are addressed and that we remain steadfast in our commitment to public safety, making certain that this Alabama problem has an Alabama solution,” Ivey said at the time.

Asked what the most significant accomplishments to address the prison crisis to date have been, and about the lack of funding for the second planned prison, Gov. Kay Ivey’s office declined to provide a response, and instead sent portions of Ivey’s most recent state of the state speech.

“The Alabama Department of Corrections certainly remains a key focus of our state’s public safety efforts. I will be frank: Running a corrections system is a hard job, and I know everyone has an opinion on how they can do it better. There is no one more capable to lead that effort here in Alabama than Commissioner John Hamm,” Ivey said in her February speech.

“Prisons around the country and on every level – federal, state and local – are experiencing challenges. But we remain committed to doing everything in our power to make improvements where we can in our state system.

“We are moving forward in our mission to build two new facilities. At the same time, we are working to stop contraband coming into our existing facilities, and we are doubling down on our staff recruitment efforts and seeing record graduating classes of officers because of it,” Ivey’s speech reads.

New buildings alone won’t solve the culture of violence and death inside Alabama’s prisons, which is exactly what the Department of Justice told the state in the 2019 report: “While new facilities might cure some of these physical plant issues, it is important to note that new facilities alone will not resolve the contributing factors to the overall unconstitutional condition of ADOC prisons, such as understaffing, culture, management deficiencies, corruption, policies, training, non-existent investigations, violence, illicit drugs, and sexual abuse.”

While no ADOC official attended the Legislature’s Joint Prison Oversight Committee meeting in December, family members of those who’ve died in state custody did, and spoke of the brutal ways in which their loved ones’ lives ended.

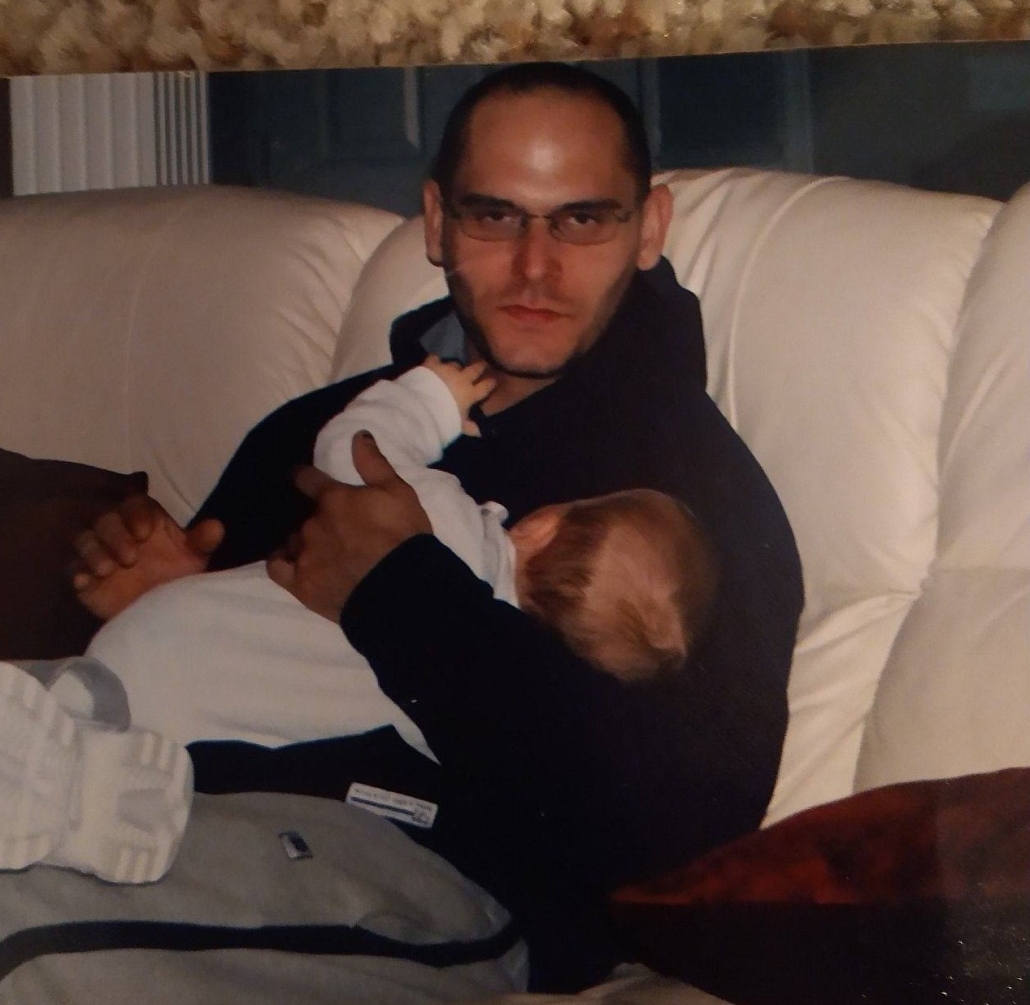

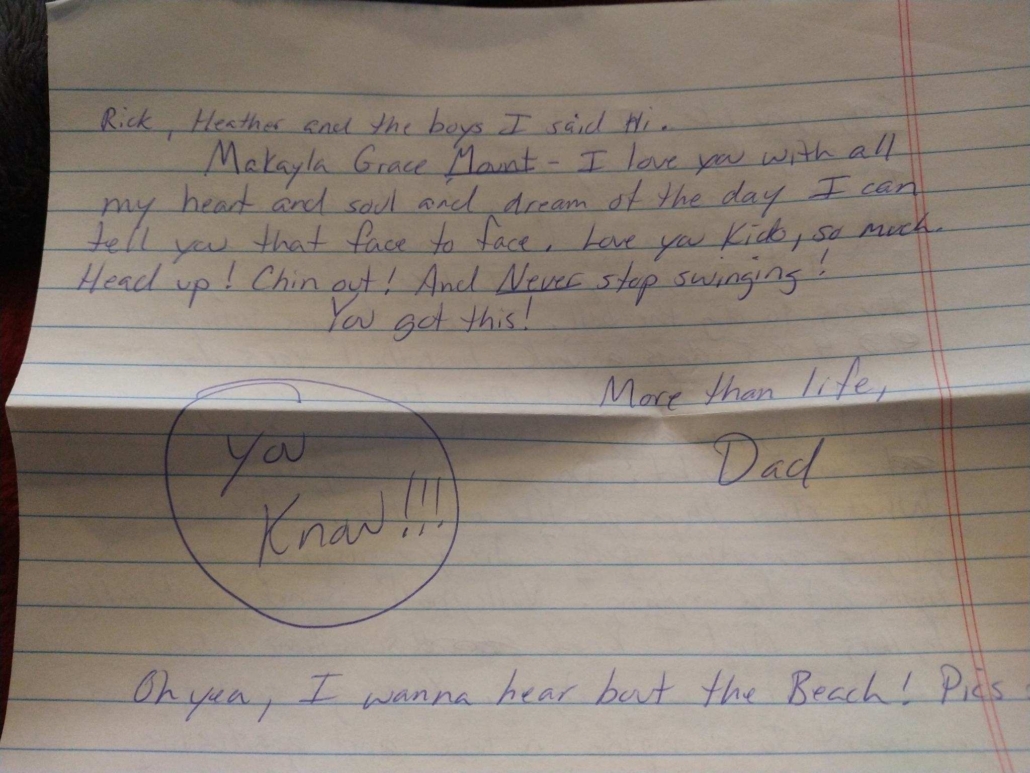

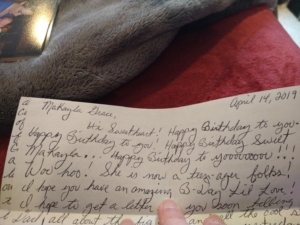

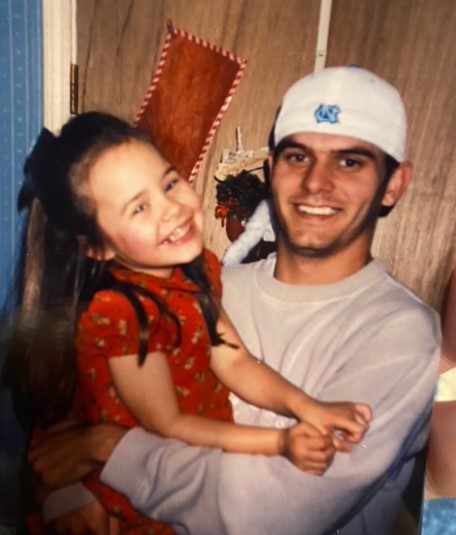

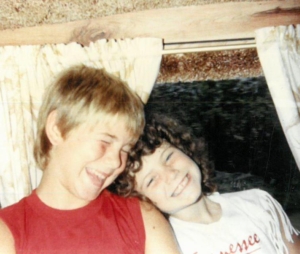

“When you see your dad for the first time in 10 years and half of his face is almost gone because he was beaten, it does something to you,”17-year-old MaKayla Mount told lawmakers at that December meeting carrying her father’s urn with her in the State House that day. Christopher Mount was beaten and strangled to death inside a protective custody cell at Easterling Correctional Facility on Mother Day 2023.

“My son was raped in February of this year and it took them over a month to get him moved,” one mother told the lawmakers at that meeting.

Appleseed’s Executive Director, Carla Crowder, described for lawmakers at that December meeting how ADOC repeatedly failed to hold accountable the 38-year-old suspect in the kidnapping, rape and torture of 22-year-old Daniel Williams, who died at a hospital on Nov. 9. The suspect was involved in nine instances of sex assault, rape, and stabbing since 2017 in ADOC while incarcerated, yet there is no documentation that the department disciplined the man or placed him in segregation.

“His classification summary showed a five-year clear record of institutional violence, which resulted in a perfect score of zero in risk assessment conducted in October, and a total score low enough for him to be placed in medium security in an open bay dorm. The psych associates signed off on this and the warden signed off on this,” Crowder said at the meeting.

These kinds of attacks are precisely what DOJ identified five years ago: “The combination of ADOC’s overcrowding and understaffing results in prisons that are inadequately supervised, with inappropriate and unsafe housing designations, creating an environment rife with violence, extortion, drugs, and weapons. Prisoner-on-prisoner homicide and sexual abuse are common. Prisoners who are seriously injured or stabbed must find their way to security staff elsewhere in the facility or bang on the door of the dormitory to gain the attention of correctional officers. Prisoners have been tied up for days by other prisoners while unnoticed by security staff.”

The report was signed by since-retired U.S. Attorneys Louis Franklin Sr., Jay Town and Richard Moore, all Trump appointees.

Alabama prisons in January were at 168 percent capacity, and held 20,469 people in combined prisons designed for 12,115. In the five years since, the state’s prison population has remained the same. At the time of the release of the DOJ’s 2019 report, Alabama prisons held just one less incarcerated person than were being housed in January, 2024.