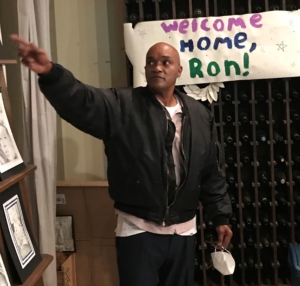

My name is Ronald McKeithen, and I am overwhelmed with joy and gratitude to be joining the staff of Alabama Appleseed as a Re-entry Coordinator and Advocate. Alabama Appleseed has added a new component to their mission: to save the lives of people who’ve been incarcerated for decades under the Habitual Offender Act are serving a slow, agonizing death sentence of life without the possibility of parole. My contribution to Appleseed’s mission is to make our clients’ transition back into society as graceful as the whole staff at Appleseed has made mine.

One year ago today, I walked out of Donaldson prison after being locked away for 37 years for a conviction received when I was a teenager. I was given a mandatory life without parole sentence in 1984. The criminal justice system in Alabama decided I was not worthy of ever living outside the prison walls. The system got it wrong, and every day I am living proof of that fact.

One year ago today, I walked out of Donaldson prison after being locked away for 37 years for a conviction received when I was a teenager. I was given a mandatory life without parole sentence in 1984. The criminal justice system in Alabama decided I was not worthy of ever living outside the prison walls. The system got it wrong, and every day I am living proof of that fact.

My background is different from most people who go to work for a legal nonprofit. I grew up with three siblings in Titusville, one of many impoverished communities in Birmingham, where thoughts of college careers were not seriously entertained over a dinner conversation. We were poor. We always lived in dilapidated housing. Sometimes I was hungry. The welfare checks and food stamps were never enough for a house of five. But like most young kids, I wasn’t aware of our struggles. Not fully, anyway.

Despite a childhood in poverty, with an alcoholic mother and an absent father, I always loved to learn. I loved school. I dreamed of being a UAB student. As a child living on the southside of Birmingham, I watched as the university grew around us until we had to move. This is why I receive such a thrill these days when I’m asked to speak to a UAB class full of students or on a panel at AEIVA (Abroms-Engel Institute for the Visual Arts) or be a witness in a mock trial. I’ve also had the extreme pleasure of speaking at Samford University twice, as well as Homewood High School. I’ve met amazing kids who will no doubt change the world.

I have always been curious about people, about life. As a child, my curiosity had me wandering all over Birmingham, roaming areas a Black child did not belong. But as an explorer, the risks were worth it. I will never forget the time I came across a hidden paradise that was right down the street. There were large crabs and crawfish, frogs with legs so large, sand that was too white to be in my ‘hood, and seashells that I’d only seen on Gilligan’s Island. To anyone else, it was a ditch. But to a seven-year-old me, it was a sanctuary. My beach. My coast. Wine bottles and all. And the most amazing thing that I learned about that ditch was how a heavy rain would create a flood of water that clears out the old and leaves new treasures.

I was reminded of that ditch during a visit to Panama City Beach a few months ago. My first time ever seeing the ocean. I had never dug my toes into sand so deep, nor seen a body of water so vast. So blue. I felt as if I were standing before God. As a kid, playing in the ditch, my imagination could never have prepared me for such a sight. For such a marvelous wonder. For the real thing. Nor could 37 years of preparation, of planning, of imagining my freedom, of how it would feel, look or taste, come close to what my eyes have seen.

I have been standing before that vast ocean in a daze since I stepped through those prison gates. I am in awe of the changes, the advancements. Birmingham has grown into a beautiful city. The opportunities before me seem endless.

This is why I love my job at Alabama Appleseed. It is my responsibility to reveal these endless opportunities to our clients – men who have been denied the simple pleasures of life for decades, pleasures that so many take for granted. This new world can be frightening to some and very confusing for others. Operating a cell phone or an ATM could feel like disarming a time bomb. The mental and emotional adjustment from living in a cell for decades to all of a sudden witnessing a universe of wonder and so much change can be very overwhelming. Believe me. I know. Which is what makes this job so ideal and rewarding.

Prison convinced me that I didn’t have the luxury of being unproductive. That I couldn’t just sit around and wait for the laws to change. Nor allow the lawmakers in Montgomery to continuously build up my hopes with bills that never pass. So I paved my own way, educated myself, and tried the best I could to prepare myself for a life in a new, foreign world, just in case I ever got a second chance. Incredibly, I got that second chance.

Despite the belief that an ex-convict who has lived in prison longer than in the free world could never make it as a free man, here I am one year later, thriving. No tickets. No criminal activity. Just a lot of making up for lost time, trying to remember what freedom was like from when I was 19-years-old. So much of everyday living has seemed like a first to me, from experiencing the sensation of rustling leaves to having my own bedroom, bathroom and TV. There also have been a lot of true firsts: I got a driver’s license, worked three jobs, paid rent, operated computers, caught the bus, bought a car, pumped gas (eventually got the hang of it); I was featured in art galleries, and I was the featured artist in art shows. I’ve been on the news and radio; spoken before legislators; featured on criminal justice panels; spoken professionally to non-profits, various committees, universities, and church groups; have been filmed by the NFL; and currently spend two days a week with at-risk kids in alternative school, reminding them that they are more than the worst things they’ve ever done.

There are no words strong enough to thank the many people who have stood beside me from day one. They have been pivotal in my obtaining the most incredible job and an opportunity to work with the most compassionate people I’ve ever met. If everyone released from prison were blessed to have a support team as mine, recidivism would become a non-issue. I’m also grateful that the Community Foundation of Greater Birmingham believes in me enough to support my role at Appleseed.

I can only hope my actions speak louder than any conviction and sentence ever will.