No money for a lawyer, no hope

After my direct appeal was affirmed by the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals and my conviction was upheld by the Alabama Supreme Court, I knew I was in real trouble. I had no money to hire a post-conviction lawyer, so I started going to the law library every chance I got to study and try to figure out a way to challenge my sentence. I began filing petitions to the court. But when you do this pro se (without a lawyer) the courts very rarely take your arguments seriously. I suppose that’s understandable when you’ve got a GED-educated guy like me trying to interpret complex laws that are intended to keep me locked up forever.

Denial after denial began to weigh me down as the months turned into years. My life philosophy became hoping for the best but expecting the worst. It didn’t help that throughout all of this disappointment, I was losing family members, one after another. I couldn’t even go to the funerals to give final good-byes.

Meanwhile, all types of violence by convicts and guards surrounded me. I witnessed several men stabbed to death, killed by people who I associated with at the time. Because of my association, I was put in some very dangerous and hairy situations. I knew that I needed to do something different or I was going to be killed myself.

Losing a father but finding a new way to live

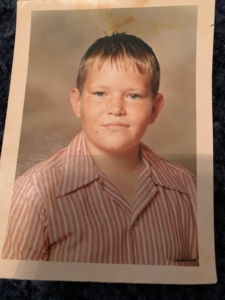

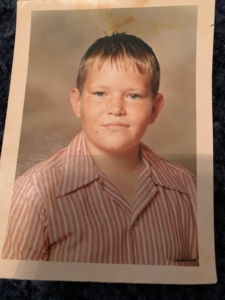

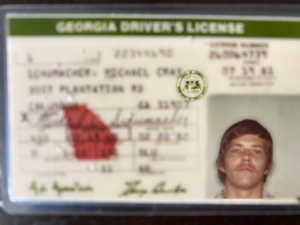

A young Michael Schumacher

My father and I were very close. After he passed away, I had a hard time dealing with the loss. I was ashamed of being such a disappointment to him. When I was young, my father wanted me to be a pilot. But I didn’t pay much consideration to my future then. I remember my dad being a heavy drinker and could be distant as a result, so as a confused teenager, I got into trouble in a reckless attempt to get his attention. Two of the offenses that contributed to me being sentenced as a habitual offender happened when I was just 17.

Even after my father was dead, I could still feel his presence and disappointment in me. I couldn’t shake this idea that even beyond the grave, he was still so ashamed of me. So, I made some changes and decided to engage in positive, productive pastimes. I enrolled in trade school and graduated with a plumbing certification. I earned my GED and became a tutor, trying to help other men get their GEDs. I went to a drug treatment program for 18 months. When I graduated, I worked as an Intern assisting staff in the daily operations of the program. Eventually, I functioned basically as an unofficial drug and alcohol counselor for ten years. (I was only a few course hours shy of earning an associates in substance abuse counseling when the program was discontinued for folks with life without parole sentences.)

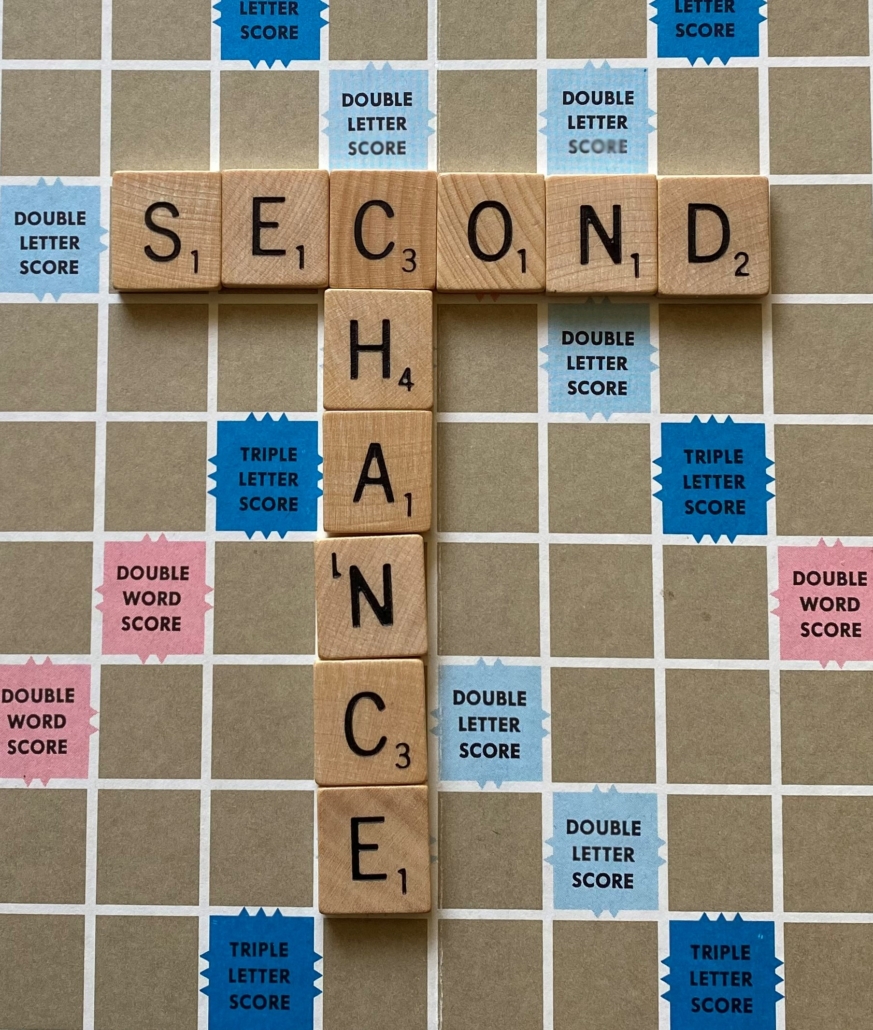

Moving into faith-based honor dorms was another important decision in my effort to improve my life. Those dorms were more clean and structured than the rest of the prison and offered a range of programming, unavailable elsewhere. There, you could find a constructive environment even while housed at one of the most dangerous prisons in Alabama. In prison, all you have is time with nothing to do, so the honor dorm classes helped in passing some long days. Classes got me out of the madness of the cell blocks or dorms. When I wasn’t in classes, I began playing Scrabble to pass the time and avoid the chaos. (I’m the reigning Scrabble champ in some of the correctional facilities.)

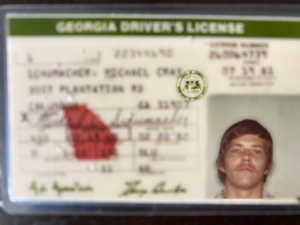

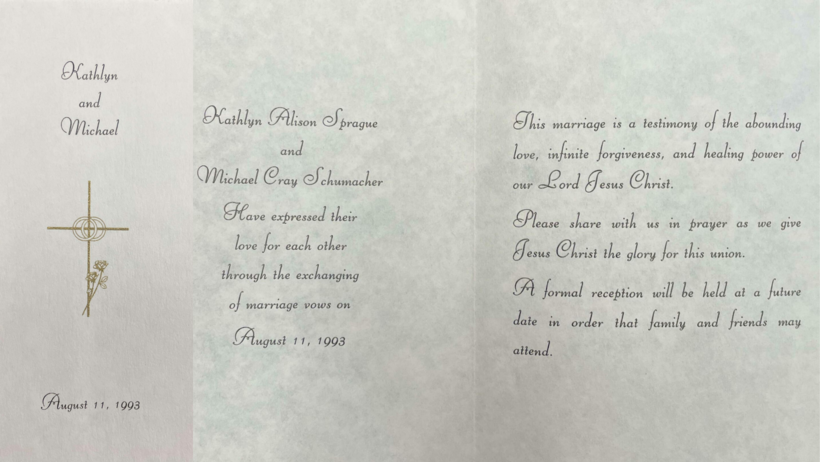

Michael’s 1983 Georgia license

Over the decades there were several people that I befriended who have hung in there with me. Usually prison pen-pals don’t last long for a number of reasons, but I have met many people who are still supportive even after my release and have been there for me over multiple decades. Gene, a retired engineer living in Texas, and I started writing in 1988. We are still friends today. I basically adopted him as a father figure. He always encouraged me to do the right things, and he helped me a great deal with my spiritual journey. In fact, he kept every letter I ever wrote him since the late 1980s and mailed them to me soon after I was released.

Then there’s Nancy, a lawyer in North Carolina. She and I have been writing since 2006 and have developed a lifelong friendship. Nancy always encouraged me to look for the positive in each day even while housed in a maximum security prison. She always told me to believe that somehow one day I would be released. I am eternally grateful for her enduring presence, encouragement, and support.

There are countless others all across the continental U.S. who have supported me endlessly with abundant generosity. (A good friend of mine from Idaho even mailed me a computer the other day!) They all stuck it out with me, year after year, and kept me stable as I came to terms with the reality that I would spend the rest of my life in prison.

“It was only a stamp and I had nothing better to do at the time.”

Michael and Carla on release day April 9, 2021 outside of Holman Prison.

Over the years, I heard that the Legislature was going to change the Habitual Felony Offender Act (HFOA), but nothing happened to help me. It wasn’t long before I didn’t even want to hear the rumors of reforms anymore and would tune out the conversations. I would never say anything negative to guys when they talked about speculative revisions to the HFOA because I knew they were just trying to hold on to the belief that one day the laws would change and they might get out and not die in prison. I used to be the same way.

One evening when I was watching the news, I saw a story about a man who was getting out of prison in Alabama after serving over 36 years for robbery on an LWOP sentence. The guy lived in the dorm next to me. We didn’t know each other, but I was sure happy for him. They mentioned the lawyer’s name who represented him so I wrote it down. From what I gathered, his crime was just like mine. So I figured I would write the attorney a letter and see if she could give me any help or advice. I really didn’t think I would get a reply, but it was only a stamp and I had nothing better to do at the time. Her name was Carla Crowder, and she worked at Alabama Appleseed Center for Law & Justice.

I did get a reply, and that surprised me. But the letter stated that it would be some months before she could look at my case and determine if anything could be done to maybe assist me in my quest. This made me think the worst, that this was a brush-off type of deal and that I’d never hear from her again. At the time, I didn’t have a high regard for attorneys.

After a few months, I was contacted by the attorney again. She was asking questions about my case and different details about how long I had been incarcerated and if I was sentenced as a habitual offender. She even sent me a stamped envelope to ensure that I wrote her back. I sure found that interesting.

Out of the blue, I was transferred to Holman Correctional Facility. (It’s common to be shuffled from one max security prison to another about every decade for no apparent reason.) Once I got there and saw how dysfunctional things were, I thought I would end up being killed there. I thought the House of Pain was bad, but it didn’t have anything on Holman! I was placed in the most violent dorm there, and I couldn’t believe the conditions. Even the guards were afraid to come into the dorms, and when they did have to come in to count, they did not come alone. Luckily for me, I had befriended some of the gangsters that were running the prison years prior, so I wasn’t treated as a “scrub.” Daily, someone was being stabbed or beat up. During my first three weeks, two men were killed in my dorm.

Things at Holman only got worse after I slipped and fell on a wet floor and had to be flown on a helicopter to a trauma center due to a broken rib and punctured lung. The guards thought I had been jumped. Coincidentally two hours later, four men were stabbed in my dorm and had to be taken by helicopter to the same trauma center where I was. I don’t think I ever convinced the guards that I simply fell. Accidents are anomalies in ADOC where intentional infliction of violence is the norm.

As I recovered from my fall, most of Holman was condemned and ordered to be shut down. They had to keep some of the prison open because it’s where Death Row is located. In addition to the inmates on the Row, they let 150 people stay, those of us considered a “low security” risk. Even though I was condemned to die in prison and had nothing to lose should I get into trouble to try to escape, I was nearing 60 and my health was declining. My COPD had gotten so bad, it prevented me from even walking to the chow hall for my meals. It was clear to anyone who’d been around me in the previous two decades that I was no real danger to anyone.

As I recovered from my fall, most of Holman was condemned and ordered to be shut down. They had to keep some of the prison open because it’s where Death Row is located. In addition to the inmates on the Row, they let 150 people stay, those of us considered a “low security” risk. Even though I was condemned to die in prison and had nothing to lose should I get into trouble to try to escape, I was nearing 60 and my health was declining. My COPD had gotten so bad, it prevented me from even walking to the chow hall for my meals. It was clear to anyone who’d been around me in the previous two decades that I was no real danger to anyone.

I continued to correspond with Carla Crowder Appleseed and another attorney at Appleseed, Alex LaGanke. They could not come see me due to pandemic restrictions, but they talked with me on the phone pretty regularly and informed me that they were working on filing a petition on my behalf. I was glad this was happening, but after so many denials in the courts, I was not as excited as some would be; I just didn’t believe anything was going to come of it.

I remember Carla asking me to get her a copy of my institutional record so she could finish my application to Shepherd’s Fold transitional center for people reentering society after prison. I came close to ignoring the request, sincerely believing the odds of getting out were infantesimal. But I had come to respect her and didn’t want to disappoint, so I went ahead and put the request in to my classification specialist. He informed me that I had LWOP, and there was no way that any transitional home was going to accept me … because I was never getting out of prison.

As I recovered from my fall, most of Holman was condemned and ordered to be shut down. They had to keep some of the prison open because it’s where Death Row is located. In addition to the inmates on the Row, they let 150 people stay, those of us considered a “low security” risk. Even though I was condemned to die in prison and had nothing to lose should I get into trouble to try to escape, I was nearing 60 and my health was declining. My COPD had gotten so bad, it prevented me from even walking to the chow hall for my meals. It was clear to anyone who’d been around me in the previous two decades that I was no real danger to anyone.

As I recovered from my fall, most of Holman was condemned and ordered to be shut down. They had to keep some of the prison open because it’s where Death Row is located. In addition to the inmates on the Row, they let 150 people stay, those of us considered a “low security” risk. Even though I was condemned to die in prison and had nothing to lose should I get into trouble to try to escape, I was nearing 60 and my health was declining. My COPD had gotten so bad, it prevented me from even walking to the chow hall for my meals. It was clear to anyone who’d been around me in the previous two decades that I was no real danger to anyone.

that was lifted from my shoulders! Once again God was good to me, Kathlyn forgave me for not being totally truthful and has vowed to stand by me until the end. I’ve never been so richly blessed in my entire life, I love her so much! I did ask her for her hand in marriage and she said she would be honored to become my wife. Can you believe it? We are officially engaged and are planning to be married here at the prison in July. It just amazes me how everything is turning out. You have always said God is working in my life and I have believed this but now it’s showing and I’m bursting with joy and happiness and last but not least thankfulness.”

that was lifted from my shoulders! Once again God was good to me, Kathlyn forgave me for not being totally truthful and has vowed to stand by me until the end. I’ve never been so richly blessed in my entire life, I love her so much! I did ask her for her hand in marriage and she said she would be honored to become my wife. Can you believe it? We are officially engaged and are planning to be married here at the prison in July. It just amazes me how everything is turning out. You have always said God is working in my life and I have believed this but now it’s showing and I’m bursting with joy and happiness and last but not least thankfulness.”