Racial Justice

It’s Past Time to Reckon with Racial Justice in Alabama

Alabama is one of the poorest states in the nation. We have one of the highest rates of African Americans per capita. We also have one of America’s highest rates of incarceration.

These facts are not unrelated. For its entire 201-year history, Alabama has prioritized maintaining white supremacy over our well-being as a state. Prosperity means letting everyone prosper, but instead, we have been governed by a series of legal schemes that privilege the wellbeing of wealthy white landowners over everyone else.

Alabama makes consistent choices that prioritize punishment and deprivation over prosperity. The consequences of refusing to invest in education, healthcare, and equitably distributed infrastructure have been devastating for many communities.

But make no mistake: by design and in practice, those consequences are borne most brutally by Black Alabamians.

Since 2017, Appleseed’s staff has collected data and stories that demonstrate how Alabama laws that are race-neutral on their face are deployed in ways that disproportionately harm, traumatize and incarcerate Black people and bleed Black families of money and resources. We’ve shown that Alabama over-polices, and over-incarcerates Black Alabamians, who comprise about a quarter of the state population but more than half its jail and prison populations. And we’ve exposed policing for profit, through mechanisms like fines, fees, court costs, and civil asset forfeiture, extracts wealth from Black communities at staggering rates.

Our research and reporting has consistently uncovered law enforcement abusing their powers. We have repeatedly found that state laws and government actors disproportionately harm Black Alabamians. As conversations about structural racism, anti-Black violence, and the need to reimagine law enforcement take center stage, we will be re-sharing some of our research that illustrates the shape of these systems here in Alabama. And we will continue to fight for an Alabama where there is no room for doubt that Black Lives Matter.

Photography by Bernard Troncale and Stephen Poff

School Policing

As par t of our school-to-prison pipeline work, we published Hall Monitors with Handcuffs. This report showed that racial disparities in policing and punishment start early, often when school resource officers (SROs) are called on to deal with basic disciplinary issues in schools. Among other things, we revealed that African American children were more likely than their white peers to be referred to law enforcement in 32 Alabama school districts, often triggering a series of events that can lead to a criminal record with devastating lifelong consequences. We also showed that African American boys with disabilities were more likely than any other children to be referred to law enforcement in Alabama schools, with a disparity of 3.1 to 1.

t of our school-to-prison pipeline work, we published Hall Monitors with Handcuffs. This report showed that racial disparities in policing and punishment start early, often when school resource officers (SROs) are called on to deal with basic disciplinary issues in schools. Among other things, we revealed that African American children were more likely than their white peers to be referred to law enforcement in 32 Alabama school districts, often triggering a series of events that can lead to a criminal record with devastating lifelong consequences. We also showed that African American boys with disabilities were more likely than any other children to be referred to law enforcement in Alabama schools, with a disparity of 3.1 to 1.

“M” is an African American boy with ADHD and a traumatic brain injury who was repeatedly arrested at middle school for things like swearing and being loud in the halls. He and his mother shared their story. “The school…is where kids are being taught basically how to handle themselves in the real world,” M’s mother told us. “But now they can’t have this learning period of making mistakes and learning from those mistakes because you done added the criminal justice system in it, and now they have to learn it being locked up and took away from their parents and families.”

Drug Policy

In 2019, we documented the fiscal and human toll of Alabama’s War on Marijuana, which disproportionately harms Black Alabamians. Alabama’s marijuana laws are some of the harshest in the country. Even as over half of Americans live in states where marijuana is legal for recreational or medical use, Alabama law enforcement makes thousands of arrests for marijuana possession every year. From 2013-2018, more than 4,500 Alabamians received felony convictions for marijuana possession.

As is so often the case in Alabama, African Americans bore the brunt of this senseless public policy. Statewide, African Americans were over four times as likely as white people to be arrested for marijuana possession, even though the two groups use marijuana at roughly the same rate. The arrest disparity was more than 10 to 1 in seven jurisdictions, including Huntsville, Dothan, Gulf Shores, Pelham, Troy, Etowah County, and Decatur. In Huntsville, where the arrest disparity was a stunning 11.2 to 1, we found that the overwhelming majority of arrests occurred in locations where the plurality of residents are Black, demonstrating how the over-policing of Black neighborhoods can wreak havoc on Black lives.

Michael Brooks, 24, and his mother Sabrina Mass, of Mobile, Ala., told us what happened when Mobile police suspected Brooks was selling marijuana out of Mass’s home. Police repeatedly terrorized the family with early morning raids, pointing a gun at Brook’s head, handcuffing Mass in her bathrobe and refusing to let her cover her breasts, and once driving Mass’s toddler-aged granddaughters into a bedroom at gunpoint while they tore apart the house in search of marijuana. All they ever found was a few grams of the substance. “We’re actually paying the police to come violate families,” Mass said. “We’re paying you to come violate our house and our home and our families. Our money, out of our hard-working sweat. Now how stupid does that sound?”

Fines and Fees

In Alabama, illegal acts from traffic tickets and fishing violations to misdemeanors and felonies carry financial penalties such as fines, fees, and court costs. Because they are over-policed, over-charged, and over-incarcerated, Black Alabamians are more likely to owe fines and fees than their white peers. At the same time, historical factors such as slavery, convict labor, sharecropping, Jim Crow, lending discrimination, redlining, and schools that were segregated and underfunded by law before the late 1960s and by white flight after that, mean that Black Alabamians have far less wealth than their white peers.

In 2018, we surveyed 980 Alabamians about their experience with fines and fees. Findings in our report, Under Pressure, were stunning. Within the justice-involved population that was paying its own court debt, over 8 in 10 had given up a necessity like rent or medicine to pay what they owed; almost 4 in 10 admitted to committing a crime; and 44% used high-interest payday or title loans to cover their debt to the state.

Eight in 10 justice-involved survey takers had borrowed money from a friend or family member to cover their court debt. To learn more about this, we surveyed 101 people who were only paying court debt for others, usually a friend or family member, and this group was overwhelmingly composed of middle-aged Black women. While other people their age were saving money for retirement, investing in the wellbeing of their children and grandchildren, and paying down mortgages, these Black women were burdened with paying court debt for their loved ones — a shocking demonstration of how Alabama’s criminal punishment system bleeds wealth from families of color.

Angela Dabney, a 40-year-old African American woman from Montgomery, told us how fines and fees have led her to terrified of police. The single mother of three children, Dabney had outstanding warrants for traffic tickets because she could not afford to keep up with her payment plans. Her driver’s license was suspended, and she could not afford to get it back. She lived in fear that a chance encounter with law enforcement would land her in jail. She was afraid to go to court and request a new payment plan, because in all likelihood, she would be jailed. “I can’t afford to do that. I’m a single parent and I have to be at home with my kids,” she told us. “I can’t get a job because of these tickets. I have to pay my bills or I’d be out on the street. So I take paying my bills over tickets. I’m sorry, it might not sound right, but it’s the truth.”

Angela Dabney, a 40-year-old African American woman from Montgomery, told us how fines and fees have led her to terrified of police. The single mother of three children, Dabney had outstanding warrants for traffic tickets because she could not afford to keep up with her payment plans. Her driver’s license was suspended, and she could not afford to get it back. She lived in fear that a chance encounter with law enforcement would land her in jail. She was afraid to go to court and request a new payment plan, because in all likelihood, she would be jailed. “I can’t afford to do that. I’m a single parent and I have to be at home with my kids,” she told us. “I can’t get a job because of these tickets. I have to pay my bills or I’d be out on the street. So I take paying my bills over tickets. I’m sorry, it might not sound right, but it’s the truth.”

Policing for Profit

In 2018, we documented how Alabama’s profit-driven civil asset forfeiture scheme works in Forfeiting Your Rights. Civil asset forfeiture is a system by which the law enforcement seizes property it suspects was connected to crime. In practice, this means Alabamians can have cars taken if they are used to transport small amounts of illegal drugs, or cash taken if law enforcement finds it during an arrest. A criminal conviction is not required for the state to keep what it takes; indeed, criminal charges do not even have to be filed.

Because Black Alabamians are over-policed, they are disproportionately exposed to having their assets seized. This is exacerbated by the fact that Black Alabamians are less likely than their white peers to have bank accounts, meaning they are more likely to have their assets in cash, which is easier to take than money in a bank.

Our findings were disturbing. Because race is not routinely reported in civil cases, it was impossible to determine the racial breakdown of all individuals who were subject to forfeiture proceedings. However, in 64% of the cases where criminal charges were filed in association with the seizure of assets, the defendant was Black. This suggests that even when white people have their assets taken for reasons allegedly associated with criminal activity, they are less likely than Black people to be charged with a crime.

In Mobile, an African American man who had just cashed a $100,000 check from a worker’s compensation settlement had the proceeds seized. The money was still wrapped in bank tape and contained in a box along with correspondence from the attorney who had represented him. Police took the money anyway after finding illegal drugs and paraphernalia on the property. They also took the man’s TV, his fiancée’s sunglasses, purses and dresses, the couple’s couches and coffee table, and two paintings. Police held onto the items even after a court ordered them returned: only when the lawyer filed a motion to hold the police in contempt did the man and his fiancée get their property back.

Another Black man in Mobile had money, electronics, furniture and football memorabilia belonging to his cousin, a former University of Alabama football star, seized when police searched his home. Despite the fact that many of the items taken were gifts from the man’s cousin, police tried to keep them anyway.

“I have never had a Caucasian client who has had a narcotics officer unscrew the TVs from their walls and take them out the front door and confiscate them,” a lawyer who litigates civil asset forfeitures told us. “However, it is a common occurrence with African American clients.”

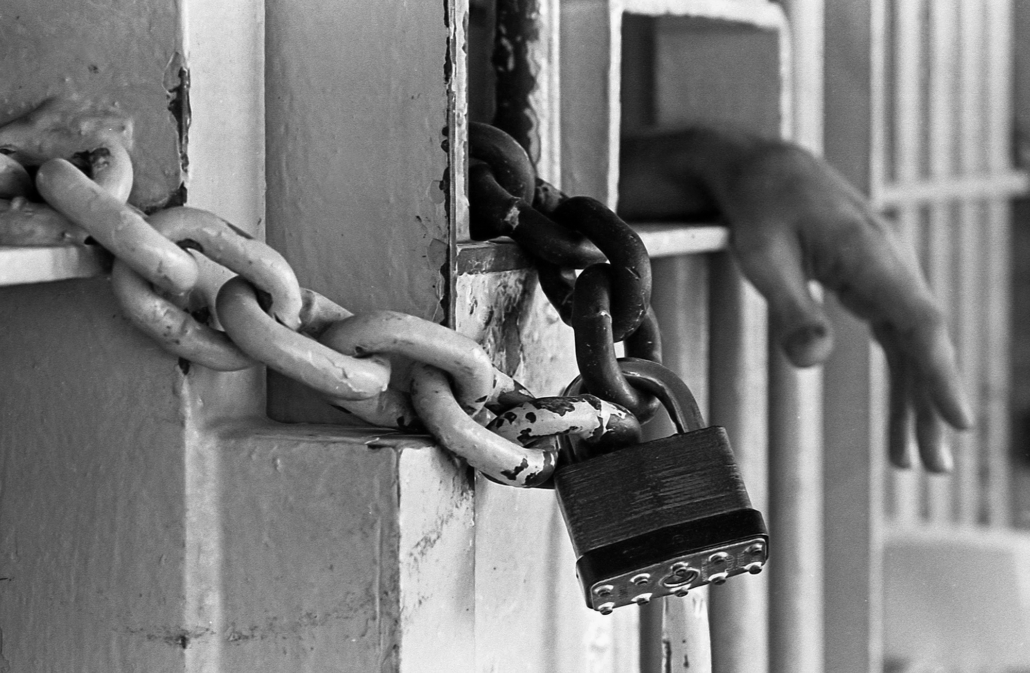

Over Incarceration

Alabama’s population is about a quarter Black, but more than half of the people in its prisons are Black. Over-incarceration results in Black men and women being disproportionately taken from families and communities, excluded from educational and job opportunities, and subjected to Alabama’s degrading and destructive prison system.

These disparities result from intentional choices by Alabama’s overwhelmingly white prosecutors, legislators, and judges. Alabama’s 41 elected district attorneys include only 3 Black district attorneys; the entire appellate court system is white. Alabama’s refusal to seriously invest in alternatives to incarceration, such as mental health and drug treatment, community corrections, diversion programs, and re-entry services, escalates the state’s reliance on prisons.

Pervasive corruption and mismanagement at the Alabama Department of Corrections means people incarcerated by the state are not safe, a fact that elected officials have known for years but refused to address, according to the U.S. Department of Justice. DOJ described Alabama prisons as “rife with violence, extortion, drugs, and weapons,” and in 2019 declared all men’s prisons in violation of the Constitution’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment.

Following that report, we developed resources highlighting the human rights crisis in Alabama’s prisons. Our DOJ report summary lays out how Alabama has failed to protect incarcerated people: high homicide rates, unchecked sexual abuse, drugs and contraband funneled in by correctional staff, and a staffing rate 65-70% short of what is needed for safety.

Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey’s proposed solution to the prison violence crisis is to invest $2.6 billion in three new mega prisons that will perpetuate the racial inequities that have dominated our corrections system for decades. Our prison policy brief explains why building new prisons will do nothing to solve old problems in Alabama.

Our work against Alabama’s Habitual Felony Offender Act resulted in release from prison for Alvin Kennard, a 59-year-old Bessemer man who spent 36 years in prison for a $50 robbery. Kennard, who is Black, now lives with his family and earns a living fixing cars at a Bessemer dealership. But hundreds of Alabamians are still serving sentences of life without parole for crimes in which there was no physical injury. Three-quarters of them are Black. “Prison is loaded with people like me,” said Mr. Kennard. “People who haven’t hurt anyone don’t deserve to be away all their life with no chance at parole. Many of them didn’t commit any violence. I’ve seen many men change in prison. If lawmakers would do away with the habitual offender act, many older people like me could get released.”

Felony Disenfranchisement

Based on the most recently available data, more than 286,000 Alabamians have had their voting rights stripped away because of past felony convictions. This number accounts for almost 8% of the state’s entire voting-age population and 15% of the Black voting-age population.

For years, there was no consistent statewide policy for determining who was eligible to have their voting rights reinstated after completing sentences; Alabama law stated only that no person with a felony conviction for a crime of “moral turpitude” could get their voting rights back. Counties were left to determine for themselves what constituted moral turpitude, leading to dramatically disparate consequences for the same crime from county to county.

Appleseed has encountered many Black Alabamians whose voting rights were stripped from them because of low-level drug offenses or court debt. In Tuscaloosa, we met a 75-year-old woman named Mary Thomas who received her first felony conviction in connection with the possession of a small amount of marijuana in 2011. Thomas, who told us “from the day they said Black folks could vote, I been voting,” lost her right to the ballot. She was unable to vote for Barack Obama during his second run for office. Thomas’s rights were restored due to a 2017 change in law that defined “moral turpitude” crimes and excluded possession of marijuana from that list. Appleseed staffers helped her register in 2018.

Appleseed has encountered many Black Alabamians whose voting rights were stripped from them because of low-level drug offenses or court debt. In Tuscaloosa, we met a 75-year-old woman named Mary Thomas who received her first felony conviction in connection with the possession of a small amount of marijuana in 2011. Thomas, who told us “from the day they said Black folks could vote, I been voting,” lost her right to the ballot. She was unable to vote for Barack Obama during his second run for office. Thomas’s rights were restored due to a 2017 change in law that defined “moral turpitude” crimes and excluded possession of marijuana from that list. Appleseed staffers helped her register in 2018.

But tens of thousands of Alabamians are still barred from voting because the 2017 law states that people convicted of most moral turpitude crimes can only vote again once they have paid all their fines and fees – an insurmountable barrier for many. Almost 56% of the people we surveyed about fines and fees in 2018 were not registered to vote due to a criminal conviction. Some of them may have been newly eligible under the 2017 change in law, but seven in 10 had not heard of the change because the state made no effort to notify people that their rights had been restored.

Alabama’s Failure to Collect Data on Race

Alabama’s willful ignorance about the damage our laws, policies, and practices inflict on residents, and particularly residents of color, is a story unto itself.

The government refuses to maintain data on the race of individuals stopped by police, so it is impossible to prove the magnitude of what most residents of color intuitively know: that Black people are more likely to be pulled over by police. Being stopped by police is a disruptive, frightening, and humiliating experience at best. At worst, it is a path to fines, fees, criminal charges, and incarceration.

Alabama does not require municipal courts to participate in its publicly available case management database, meaning that hundreds of thousands of data points about low-level offenses like violations and misdemeanors which could tell us who is detained by municipal law enforcement and what happens to them are difficult, if not impossible, to come by.

Alabama declines to maintain demographic information about individuals from whom property is seized and forfeited to the state, meaning that if no criminal charges are filed against an individual whose property is taken on suspicion of illegal activity, we have no way of knowing that person’s race — even as we know that asset seizure is a common byproduct of the types of traffic stops and searches to which we know communities of color are disproportionately subject.

Alabama declines to maintain demographic information about individuals from whom property is seized and forfeited to the state, meaning that if no criminal charges are filed against an individual whose property is taken on suspicion of illegal activity, we have no way of knowing that person’s race — even as we know that asset seizure is a common byproduct of the types of traffic stops and searches to which we know communities of color are disproportionately subject.

The state also chooses not to collect demographic information about participants in diversion programs like drug courts, pretrial diversion, and court referral that can help low-level offenders avoid criminal convictions and incarceration. Though flawed and too expensive, these programs are the best shot many individuals have at a clean slate. It is crucial to ensure they are accessible to all Alabamians regardless of race. Alabama Appleseed’s own data collection in 2018 and 2019 suggests that African Americans are underrepresented in diversion programs. Data about the racial breakdown of participants in Community Corrections, the one diversion program that does collect demographic information, points in the same direction. In 2018, the population of Community Corrections programs statewide was about 41% Black, more than 10 percentage points lower than the percentage of the state prison population of the same race. Community Corrections participants enjoy a measure of liberty denied the rest of the prison population. And African Americans, who are already overrepresented in Alabama’s correctional system, are again disproportionately held in the most miserable, dangerous, and punitive form of custody, Alabama’s notorious and unconstitutionally cruel and unusual prisons.

Sign up here to join our network of advocates across Alabama.

Support the work of Alabama Appleseed by donating today!