Economic Justice

Alabama criminalizes poverty. We all pay the price.

Poverty is not a crime. But in Alabama, people who lack access to wealth rarely experience equal justice under law.

Alabama has long been one of the poorest states in the nation. Currently, more than 800,000 Alabamians live below the poverty line.

The causes of Alabama poverty are complex and include historical factors like a state constitution that restricts fair and equitable taxation. But present-day choices worsen and further entrench poverty in Alabama, diverting people away from the workforce and into an endless spiral of punishment. Specifically, the decision to bypass taxes and rely on court fines and fees in minor traffic offenses and criminal cases to fund essential state functions creates devastating consequences for people who cannot afford those costs.

Since 2017, Appleseed has documented the ways in which Alabama’s two-tiered criminal legal system means that people with access to wealth fare far better than those who lack it. Our findings are staggering.

In Alabama, access to money can mean the difference between participating in a diversion program, such a drug court, and having your conviction set aside or pleading guilty to a felony and living with a stain on your record that will never wash away.

It can mean the difference between having the freedom to drive and having your driver’s license suspended.

It can mean the difference between being allowed to vote and being barred from fully participating in the democratic process.

It can mean the difference between freedom and incarceration.

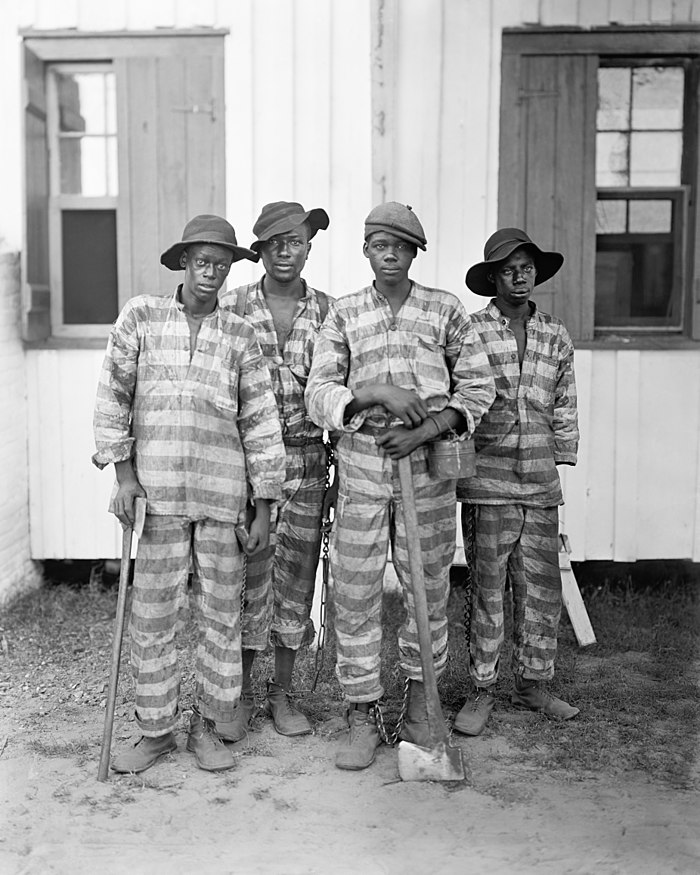

The historical reasons for Alabama’s racial wealth gap are well known. More than a century of enslavement, followed by another of sharecropping, convict leasing in which Black people convicted of vague offenses such as vagrancy were forced to work in coal mines, legally enforced segregation, and other mechanisms of de jure white supremacy mean that Black families here have historically lacked equal opportunities to accumulate wealth. This brutal past birthed a present filled with lesser, though still pernicious, obstacles to economic advancement for Black Alabamians. These include regressive taxation, segregated and unequal schools, lending discrimination, income inequality, and a criminal punishment system that disproportionately polices and incarcerates Black Alabamians and also strips Black families of wealth via the invisible tax of fines, fees, and court costs mean that Alabama’s racial wealth divide continues to gape.

Alabama is one of the poorest states in the nation. It also has one of America’s highest rates of incarceration. Alabama Appleseed uses original research and reporting to connect the dots between these two realities so we can thoughtfully tackle policies that reinforce our poverty to prison pipeline.

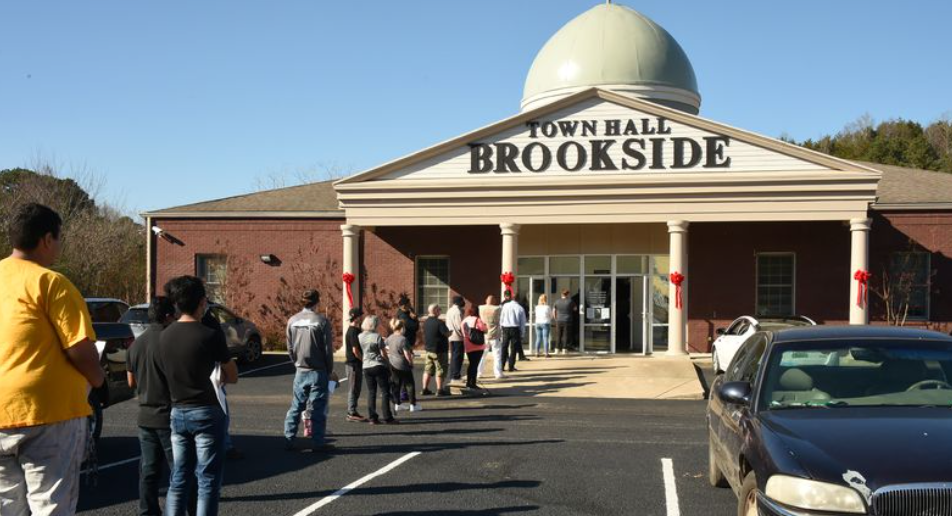

“A black hole.” That’s what Jefferson County District Attorney Danny Carr called Brookside, Ala. (pop. 1,253), in the story that exposed it as likely the worst speed trap in America.

“Garbage.” That was the word Jefferson County Circuit Judge Shanta Owens used to describe the credibility of Brookside police officers before dismissing a cluster of traffic cases in which they were the sole witnesses.

Brookside’s reputation as a national poster child for policing for profit is well earned. In 2022, AL.com broke the story of how the city’s aggressive policing tactics, which included the use of unmarked vehicles and officers who operated well outside of the city’s police jurisdiction and used pseudonyms to make it impossible for motorists to identify who ticketed them, resulted in a 640% increase in revenue from fines and forfeitures between 2018 and 2020. Arrests skyrocketed during those years, and the city became notorious for the long lines and abusive practices at its municipal court. By 2020, fines and forfeitures comprised 49% of the municipal budget.

Meanwhile, hundreds of motorists reported being ticketed on made-up charges like driving in the left lane, which is not illegal in Alabama. Some of the abusive policing was especially harmful to Black motorists. People were even stranded on the side of the road after Brookside police had their vehicles towed by Jett’s Towing, a small company that made a fortune on its dealings with the town. Together with the city, Jett’s faces a lawsuit alleging RICO (racketeering) and other violations.

The kinds of abusive policing practices uncovered in Brookside bubble to the surface on a regular basis in Alabama. In 2017, the south Alabama hamlet of Castleberry, (pop. 550) made headlines after it quintupled its police force, opened a municipal court, equipped its new hires with military-style fatigues and unmarked cars, and began aggressively policing the road into and out of town. Between fines, fees, forfeitures, and towing fees, Castleberry doubled its revenue in a single year and soon found itself facing litigation alleging illegal policing practices and civil rights violations. A few years before that, the Shelby County town of Harpersville made national headlines for running a debtor’s prison, with police and a private probation company collaborating to squeeze money out of poor motorists or jail them when they could not pay.

As far back as 1975, the police department of Fruithurst, (pop. 250), a notorious speed trap on the Georgia-Alabama border, met its maker at the hands of then-Attorney General Bill Baxley, who took the rare step of opening an office in the town and offering to defend drivers ticketed by Fruithurst police. A week after Baxley’s impromptu office opened, Fruithurst disbanded its police department.

Alabama’s current attorney general has not seen fit to comment on the situation in Brookside, but Baxley is still at it: Along with legendary Jefferson County civil rights lawyer Bill Dawson, he is counsel on one of more than a dozen lawsuits filed against the tiny town since AL.com began its groundbreaking coverage.

Aggressive reporting on Brookside netted positive results for all Alabamians, not just those named in lawsuits. In 2022, amid bipartisan calls for accountability and reform, state lawmakers swiftly passed two pieces of legislation aimed at deterring predatory police practices. One caps at 10% the percent of a municipality’s revenue that can come from traffic fines. The other requires municipalities to provide information about revenue from tickets, along with data about their budgets and certain expenditures, to a statewide database.

Brookside’s former police chief, Mike Jones, resigned shortly after AL.com’s stories began rolling in. He kept his badge though – and in May 2022 he was arrested in Covington County for impersonating a police officer after he flashed his badge during a traffic stop where a deputy claims he was going 78 mph in a 55 mph zone.

Just days before Jones’ arrest, another former Brookside police officer was arrested on charges of first degree rape. And Officer Mike Savelle, Jones’ second-in-command, had been arrested in Hoover, Ala. on charges of public intoxication and harassment three years earlier. Savelle retained his position in Brookside despite the charges, only resigning after the 2022 stories of abusive policing broke.

“I can’t stand a dirty cop,” Covington County Sheriff Turman told AL.com. “I can stand a thief better than a dirty cop. All they do is take people’s rights. I can’t stand them.”

Fines and Fees

In Alabama, convictions for unlawful acts ranging from traffic tickets and fishing violations to misdemeanors and felonies carry financial penalties such as fines, fees, and court costs. These legal financial obligations are a burden to everyone who incurs them, but people who lack access to wealth suffer disproportionately.

In Alabama, convictions for unlawful acts ranging from traffic tickets and fishing violations to misdemeanors and felonies carry financial penalties such as fines, fees, and court costs. These legal financial obligations are a burden to everyone who incurs them, but people who lack access to wealth suffer disproportionately.

In 2018, we surveyed 980 Alabamians about their experience with fines and fees. Our findings were stunning. More than eight in ten justice-involved survey-takers had given up a necessity like rent or medicine to pay what they owed. Almost four in ten admitted to committing a crime to cover their debt to the state.

Jonathan Roberts, a 25-year-old man who was living at Mobile’s Waterfront Rescue Mission at the time he was interviewed, shared that the state’s practice of assessing additional penalties against people who cannot afford to keep up with payments has at times left him feeling hopeless.

“I know I messed up when I was young, but let’s try to move forward,” he said. “Because if not, being in debt, it makes the bad side so much easier than the good side. And if you want to stay on the good side, you need a little help. Just a little. A pat on the shoulder, or just, ‘We’re not gonna put you in jail this time because you can’t pay.’ But having to fear the police is not right, because of debt.”

Second Chances – for Some

Low-level offenders in Alabama are frequently offered the opportunity to get a clean slate or serve their sentences outside of prison walls by participating in diversion programs. In 2020, we documented how structural and financial obstacles make these programs difficult to access for people who lack wealth.

Low-level offenders in Alabama are frequently offered the opportunity to get a clean slate or serve their sentences outside of prison walls by participating in diversion programs. In 2020, we documented how structural and financial obstacles make these programs difficult to access for people who lack wealth.

We surveyed 1,011 justice-involved Alabamians, asking those who were involved with diversion how those programs affected their daily lives. Most of our survey-takers were poor: 55% of them made less than $14,999 a year. Yet the median amount they reported paying for diversion was $1,600 – more than 10% of their total income. Only one in ten had ever been offered a reduced fee or fee waiver based on their inability to pay.

Even making those desperate choices, some people couldn’t afford the price of a “second chance.” One in five had been turned down for a diversion program because they could not afford it, and about the same proportion had been kicked out of a diversion program because they could not keep up with payments.

Kiasha Hughes, a young mother from Tuscaloosa, was offered an opportunity to participate in the district attorney’s Second Chance Diversion Program after her arrest for possession of marijuana. Successful completion of the program would have led to a clean record and a chance to start fresh. But Hughes, who was pregnant with her second child and still working a third-shift job so she could look after her little girl during the day, realized she would never be able to meet the program’s time-consuming demands or pay the $1,000 fee plus fees for drug testing. Instead, more than two years after her arrest, she pleaded guilty to misdemeanor possession of marijuana. She received a year of probation and a bill for $1,440 in court costs.

Driver’s Licenses

Alabama suspends drivers’ licenses for four reasons that have nothing to do with road safety: failure to pay traffic tickets, failure to appear at hearings about those unpaid tickets, drug offenses including unauthorized possession, and failure to pay child support.

The collateral consequences of losing a license are staggeringly disproportionate to the offenses that prompt suspension. An Appleseed survey of Alabamians whose licenses were suspended in connection with unpaid tickets found that:

Appleseed has spoken with countless Alabamians who lost opportunities after their licenses were suspended because they couldn’t afford to stay current on their traffic debt. In Montgomery, we met Angela Dabney, a single mother of three who lost her license in connection with unpaid traffic debt. Dabney, 40, was overjoyed when she got a job packing goods for a moving company. But she was fired after a background check revealed her unpaid tickets and suspended license.

Civil Asset Forfeiture

Civil asset forfeiture is a system by which the law enforcement seizes property it suspects was connected to crime. Though it was sold to the public as a way of taking ill-gotten gains from drug kingpins, our research shows that much of the time, it’s used to take small amounts from vulnerable people.

Civil asset forfeiture is a system by which the law enforcement seizes property it suspects was connected to crime. Though it was sold to the public as a way of taking ill-gotten gains from drug kingpins, our research shows that much of the time, it’s used to take small amounts from vulnerable people.

In 2018, we examined 1,110 cases in 14 counties, representing 70% of the 1,591 civil asset forfeiture cases filed in Alabama in 2015. The median amount taken was less than $1400. It costs more than that to hire a lawyer to fight to get the money back from the state. As a result, many people from whom small amounts are seized never contest the seizures in court.

Since our report was published, Alabama has passed two reforms intended to rein in abusive practices. In 2019, the lawmakers voted to require law enforcement agencies to create a public database showing what they were taking via forfeiture. In 2021, they passed a law that among other things set thresholds for the value of property that could be taken via civil forfeiture. Cash worth less than $250 and vehicles worth less than $5,000 can no longer be civilly forfeited.

But those thresholds would not have helped Mary Thomas, a 75-year-old woman who was convicted of a felony after a confidential informant told police that she was a recreational cannabis user. The police raid traumatized Thomas, who remembered police rifling through the pockets of the housecoat where she kept spending money and taking everything they found.

Thomas experienced that as theft, but what had in fact happened was a civil seizure. Police claimed the $378 they took was connected to illegal activity. Thomas was not aware she could contest the seizure – and even if she had known, it would have cost her more to retain a lawyer to fight the state than the $378 that was in question.

In the end, the state kept her paycheck without ever lifting a finger to demonstrate the cash it seized was in any way connected to criminal activity. Thomas never saw that money again.

Felony Disenfranchisement

Based on the most recently available data, more than 286,000 Alabamians are being denied the right to vote because of past felony convictions. This number accounts for almost eight percent of the state’s entire voting-age population and 15 percent of the Black voting-age population.

Based on the most recently available data, more than 286,000 Alabamians are being denied the right to vote because of past felony convictions. This number accounts for almost eight percent of the state’s entire voting-age population and 15 percent of the Black voting-age population.

For years, there was no consistent statewide policy for determining who was eligible to have their voting rights reinstated after completing sentences. Instead, Alabama law stated only that no person with a felony conviction for a crime of “moral turpitude” could get their voting rights back. Counties were left to determine for themselves what constituted moral turpitude, leading to dramatically disparate consequences for the same crime from county to county.

That changed in 2017, when a new law finally defined “moral turpitude” crimes, ending the patchwork system where the same offense could lead to wildly divergent outcomes depending on the county in which it occurred. But that same 2017 law stated that people convicted of most moral turpitude crimes could only vote again once they pay all their fines and fees – an insurmountable barrier for many.

Robert Peoples of Mobile is one of them. More than two decades ago, Peoples was convicted of a felony after writing and signing checks that did not belong to him. He was sentenced to 12 years in an Alabama prison. When he finally made it out of state supervision, he left Alabama to find work and build a life elsewhere, but home always called him back. When he returned in 2012, one of the first things he did was fill out a voter registration form at the local DMV.

A voter card arrived in the mail — but it was followed by a letter from the Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles. The letter stated that Peoples could not vote until he paid about $300 in fines, fees, court costs and restitution that lingered from his decades-old conviction. He lives paycheck to paycheck and doesn’t know when he will be able to pay it off. He doesn’t know that he ever will.

Alabama’s Racial Wealth Gap

Economic injustice and racial injustice share some common features, but they are not identical phenomena. Many people of color experience discrimination and disparate treatment or outcomes regardless of their financial status, and many people who lack access to wealth struggle with structural obstacles regardless of the color of their skin.

Economic status is not and should not be used as a stand-in for race, and race is not and should not be used as a stand-in for economic status.

In Alabama, racial and economic injustices amplify each other. Over the centuries, white Alabamians have had greater opportunities to accumulate and hold on to wealth, while also avoiding race-based discrimination that continues to impact their Black peers. This adds up to a double advantage for white Alabamians, who as a result are only half as likely to live in poverty as their Black neighbors. If we are to truly achieve equity and justice for all, Alabama must recognize and dismantle both these forms of injustice.