Approximately 6,520 individuals are serving sentences of life with parole, life without parole, or virtual life in Alabama’s prisons. Most will never get released from prison.

REPORT HIGHLIGHTS

PROFILES

Earlie Whitaker: His last conviction was in 1965. He’s been on parole 44 years.

A couple years ago, Appleseed received a letter from a family member of a 77-year-old man who was on parole in Alabama. Nothing unusual about that fact alone. Our criminal justice system’s embrace of extreme sentences and permanent punishment results in thousands of people in prison and on parole who are AARP eligible.

But Earlie Whitaker had not been in trouble since the Lyndon B. Johnson Administration. His conviction was in 1965. He earned parole in 1981. But because he’d been sentenced to life in prison, he remained on parole after 44 years of dutifully reporting, avoiding new convictions, and handing over $40 per month in parole supervision fees.

This seemed to us an inefficient use of resources. Someone at the Bureau of Pardons and Parole had to keep track of Mr. Whitaker. Someone else had to process his payments. And he had to abide by various controls over his movement, then part with a chunk of his Social Security check every month. Did we really need to deploy this much bureaucracy to ensure a senior citizen who had not committed a crime since before the first moon landing stayed out of trouble?

Probably not.

While Alabama has a mechanism for people who have done well on parole after a minimum of three years and paid all their court debt to receive a pardon, which ends parole supervision, somehow, despite decades of eligibility, Mr. Whitaker has not been pardoned.

And he has plenty of company. Through public records requests, we learned that 72 Alabamians, originally sentenced to life with parole, have been on parole more than 30 years. Nearly 400 have been on parole 15 years or more. Though not all of them must report monthly, most do.

Through correspondence with people incarcerated on life sentences, we learned of others who had been successful on parole for a decade or longer. Then, following arrest on charges that did not hold up in court, parole was revoked and they were back in Alabama’s overcrowded, dangerous prisons, now in their 50s and 60s.

Appleseed is enormously indebted to Earlie Whitaker and the hundreds of justice-involved people who write to us about their experiences. From these letters, along with subsequent conversations conducted during legal visits in prisons across the state, we developed an understanding of the vast, often detrimental, and at times downright absurd implications of a corrections system that incarcerates more than 6,500 people under sentences of life without parole, life with parole, or life-equivalent, plus another 1,100 life-sentenced individuals on parole, forever.

With this report, we share their stories, their struggles, and, thankfully, some of their successes, which prove that in many cases, lifetime correctional control is completely unnecessary.

Earlie Whitaker was convicted of a serious offense in 1965, attempted murder, after he shot a woman while stealing her car. He spent 16 years in prison for his crime. And that was enough, as he never reoffended. He learned from his mistake. And he deserves his life back before it’s too late.

Archie Hamlett: Permanent Parole. and now revocation, for a 1995 Marijuana Conviction

Hazel Green, Ala. – In 1995, Archie Hamlett was sentenced to spend the rest of his life in prison for a marijuana trafficking conviction. His life without parole sentence, imposed under Alabama’s Habitual Felony Offender Act, was mandatory because he had been convicted of nonviolent, property offenses at age 16.

Now 53, Mr. Hamlett would go on to serve more than 22 years in Donaldson Correctional Facility before a combination of changes to the law, extraordinary legal advocacy, and, finally, a parole grant in 2017 allowed him to walk free. Or so he thought.

His life since then had been marked by a steady series of achievements – earning a Commercial Drivers License, starting his trucking business, renovating a house, restoring vintage vehicles, and making plans to develop 17 acres of beautiful land he purchased in booming Madison County. “When I went to prison with life without parole, I engulfed myself in learning the law so I could find my way home,” Mr. Hamlett said.

A traffic stop on a cold night in January of 2025 interrupted this life. Madison County Sheriff’s deputies checked his record, learned of his history, and detained him. Experiencing nausea and suffering from a documented medical condition involving frequent urination, Mr. Hamlett requested access to his truck for a portable urinal. The deputies refused this request. He faced the choice of urinating on himself outside on a 35-degree night or discreetly relieving himself in the dark. Mr. Hamlett, who has an immaculate record of compliance with no violations, infractions, or arrests of any sort during more than seven years on parole, chose not to humiliate himself by urinating in his pants on a frigid night. For that decision, he was charged with public lewdness, a misdemeanor, and booked into the Madison County Jail. His arrest triggered additional involvement by the Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Parole.

On March 4, 2025, Mr. Hamlett appeared in front of a Pardons and Parole hearing officer and did not dispute that he urinated outside. Explaining what happened, he stated: “I wasn’t trying to be disrespectful. I had to use the bathroom. I have a medical problem and I had to use the bathroom bad. I had a medical urinal, but they wouldn’t let me use it. I used the bathroom outside.” The officer recommended 45 days of confinement. The Parole Board fully revoked his parole, sending him back to prison to serve out the full life term, unless he is granted parole again.

In May, a Madison County judge agreed to dismiss the public lewdness case, when Huntsville attorney Richard Jensen explained the circumstances and provided medical records. Archie Hamlett remains housed in Kilby Correctional Facility, an antiquated prison designed for 440 with a current population of more than 1,300.

Until his revocation, home was a spotlessly renovated three-bedroom house in Hazel Green with a cherry-red 1968 Cutlass in the driveway, one of many vintage finds from Mr. Hamlett’s backroads adventures. He used to scout the North Alabama countryside for old vehicles in need of rescue while running loads in his 26-foot box truck, Hamlett Logistics painted on the side. He even figured out how to make extra money by taking on “hotshot” jobs: “Everything I’m running is already late so they pay more.”

He was a business owner, homeowner, entrepreneur with a flawless record reporting to his parole officer and staying clear of any legal trouble. Since 2017, he had been required to report in-person once a month to his parole officer, then check in by phone every two weeks. He paid $40 per month in “supervision” fees, totaling more than $4,000 over the course of his parole. Yet, Mr. Hamlett was still not completely free, as the traffic stop and subsequent revocation proved.

All of this government control of his movements was based upon the fact that Mr. Hamlett was convicted of trafficking in marijuana in 1995 then sentenced to life imprisonment based on nonviolent offenses committed when he was a child. In some ways, Mr. Hamlett is fortunate, given that he was originally supposed to die in prison. Birmingham attorney Richard Storm represented Mr. Hamlett in post-conviction proceedings, securing a reduced sentence to life with parole by arguing this original sentence was “grossly disproportionate” to the nature of the crime and no longer mandatory. Mr. Storm then represented Mr. Hamlett before the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles, securing his release on parole at the first hearing, a rarity for someone serving a life sentence.

But Alabama’s justice system, which created mechanisms to remedy the most draconian excesses of the original 1977 Habitual Felony Offender Act, retains features that are grossly out-of-step with public safety. Few people better illustrate this reality than Mr. Hamlett, a business owner who remains under government supervision and surveillance based on a decades-old conviction for marijuana. Before his 2025 revocation, he was making plans to grow his business and longing for the day when he could freely run a truckload of auto parts up to Ohio, or even Canada, without jumping through a bunch of unnecessary hurdles.

Alabama’s Criminal Code does contain mechanisms to loosen the grip of parole supervision. However, parolees may not be reviewed for discharge until they have “satisfied all financial obligations owed to the court, including restitution.” Mr. Hamlett was ordered to pay $25,000 in restitution, an amount that grew to $34,000 because of automatic interest added when people cannot immediately pay the full amount upon release from incarceration. Although he complied with his monthly payments – until his revocation – he could not afford to quickly pay off that exorbitant amount while continuing to invest in his business and support himself.

His entrepreneurial spirit remains undeterred by the government’s grip on his freedom. He hopes to develop his land into a tiny home community for veterans or seniors. There is a pond where older folks could fish. Pine trees for shade. And all those vintage vehicles to remind them of their glory days. His next parole consideration date is March of 2026.

Steve Scott: At age 20 he walked away from a minimum-security prison in 1993. He’s still being punished for it.

Birmingham, AL – Anyone with a passing interest in our legal system has heard of cases that highlight the ways in which justice is in short supply for those charged with crimes. Countless examples exist of young people who were caught up in the system with cases that derailed the rest of their lives. There are ample examples of people who committed relatively minor offenses which resulted in disproportionately harsh sentences. Many involve poor people who were unable to afford an attorney and received inadequate legal counsel from their court appointed attorney. You would be hard pressed to find any single case that illustrates all of these issues in a more egregious way than that of Appleseed client, Steve Scott, who walked away from Frank Lee Youth Center at age 20 and will be punished for that offense for the rest of his life.

Born in Montgomery, he never met his father, and his mother was unable to care for him as a child. He lived with his grandmother until she died when he was 8-years old, then he went to live with his aunt. Unsurprisingly, this lack of stability led Steve to struggle with behavioral issues from a young age. He was arrested for the first time at 11 years old and placed on juvenile probation. After repeatedly running away from his aunt’s home, he was committed to the Alabama Department of Youth Services (DYS). By the age of 16, he was sent to the DYS Mt. Meigs facility. When he was 17 years old, he ran away from Mt. Meigs and was charged with Escape 3rd Degree.

While out on bond for the escape charge, Mr. Scott’s low-level criminal behavior continued as he broke into two gas stations to steal beer and cigarettes. He was charged with burglary and theft then advised by his attorney to plead guilty to three felonies and accept a two-year prison sentence. While serving his sentence, at the age of 20, Mr. Scott walked away from an unsecured recreation area. He was apprehended the following morning and charged with first-degree escape, a Class B Felony.

Mr. Scott was appointed an attorney who warned him that he was facing a sentence of life without parole which could only be avoided if he plead guilty and accepted a life sentence which would leave him eligible for parole. Given that a life without parole sentence would have been illegal as a life sentence was the maximum possible under the law, the only charitable way to describe this attorney’s efforts here is gross incompetence. Charged with a crime involving no allegation of violence at only 20 years old with a relatively short criminal history, Mr. Scott should have been sentenced to far less than the statutory maximum possible sentence. Instead, on the advice of his attorney, Steve accepted the plea offer for the statutory maximum punishment of life in prison.

The hopeless nature of receiving a life sentence at the age of 20 could have led Mr. Scott to make further mistakes and fall into a life of violence and drugs inside prison. Instead, Mr. Scott somehow found direction. He stayed out of trouble and took classes to learn job skills. By 1997 at the age of 26, his institutional record led to a parole grant as soon as he became eligible. With a lack of formal education and felonies on his record, Mr. Scott’s career options were limited, but he set about learning how to paint and work construction. In 2000, his parole officer saw fit to place him on an annual reporting program and approved him to move to West Virginia where his mother and brother were living. After having limited contact with his mother growing up, he was finally able to build a relationship with her. Over the next eight years, he got married, had a child and found stability in his life for the first time. In 2008, Mr. Scott was told that the program was being discontinued and he would no longer be allowed to live out of state. His life turned upside down, he moved back to Alabama and attempted to start over.

From that point forward, Mr. Scott struggled to find consistent work. Despite his financial difficulties, he never resorted to crime after leaving prison. He reported consistently to parole for two decades, but as time went on and his financial struggles deepened, he failed to report in 2019 which led to him to be revoked to jail for 45 days. After he was released, he had lost his job and depression over his situation made finding another one difficult. In 2022, he once again did not have the money to pay his supervision fees and missed a monthly report to his parole officer. This time, due to a change in the law, Mr. Scott was automatically revoked to prison to resume serving his life sentence on the escape conviction from decades earlier.

He tried, and failed, to get a judge’s attention on his own:

“I, Steve Scott, #168598 am currently being held at Childersburg Work Release. Since being incarcerated I have completed SAP program and Life Skills at ATEF in Columbiana, Alabama. … I was out in the world for a total of 26 years on parole before the violation I am being held for now. I am asking that the Court reconsider my sentence and allow me to return to society to become a productive citizen and taxpayer.”

Despite having not committed a felony since 1992, Mr. Scott spent the next three years back in prison missing out on the things the rest of us take for granted. He lost his brother and was unable to attend the funeral. He missed three of his granddaughter’s birthdays. Somehow, he managed to avoid losing hope and focused on taking classes and working to prove he did not belong in prison. In January of 2025, Appleseed attorney Scott Fuqua represented Mr. Scott in front of the parole board. By a vote of 2-1, he was granted parole and regained his freedom. Today, he works hard at a truck-washing business and at trying to rebuild his life.

Tyrik Treadwell: A 65-year sentence for a 14-year-old honor student

Limestone Correctional Facility, Harvest, AL – Tyrik Treadwell’s incarceration can be traced to the basketball courts at a recreation center in Roanoke, Alabama. He was 14 and loved to shoot hoops. So did Charles Brown. At 29, Brown had already been convicted of two felonies, placed on probation, then had probation revoked after an attack on a woman. Following a short prison stint, he was back home and found his way to the rec center.

“He would tell me, ‘Come chill with me later on.’ We’d go by his house. I felt accepted by this person, to do what I wanted around them, versus going home and abiding by the rules,” Mr. Treadwell shared during a visit with Appleseed at Limestone Correctional Facility.

At home, Mr. Treadwell’s mother had high expectations. She made sure he was an honor roll student. Mr. Treadwell comes from a family of community leaders. His grandmother, Tammi Treadwell Holley, was a longtime town council member in Roanoke; his late grandfather a decorated Air Force veteran. And his great grandfather served in the Fire Department in the small East Alabama community. “My mother’s side is really strict,” Mr. Treadwell acknowledged.

More than a decade into a prison sentence that was unfathomable to his ninth grade self, shooting hoops and trying to impress older guys at the rec center, Mr. Treadwell wishes he had not rebelled against his mother’s strict rules. He knew he was vulnerable because his own father was in and out of his life, serving prison time. Charles Brown and his crowd, “They claimed to be inspiring. They were telling me things like, ‘You need to finish school,’ as they were handing me a beer.”

January 12, 2013, they set in motion events that delivered a young teenager with high hopes into the prison system. That’s when 14-year-old Tyrik, enamored with his new older friends, graduated from basketball and beer to be lured into a simmering feud among adults in the community. All had backgrounds in drugs and/or felony criminal records. Except, of course, Tyrik. Two young women, both adults, also came along. That night, Rodriguez Staples, 30, who had just been released on bond for a pending theft case, following drug convictions, suffered multiple gunshot wounds and died at a Traveler’s Inn. Tyrik and Brown were charged with capital murder.

Tyrik’s attorneys filed a motion with the trial court requesting he be tried under Alabama’s Youthful Offender Act, a special status granted at the court’s discretion in criminal proceedings where the accused was under 21 years of age at the time of the offense. If granted the court records would be sealed and the case would be handled separately from adult criminal proceedings. The motion was denied by the court nearly five years later, on the first day of his trial when he was 19 years old. The court allowed Tyrik’s grandmother, Tammi Holley, to sit with him at the defense table for support.

Tyrik was tried before an all-white jury in a county where 20% of residents are Black. The State relied on testimony from the two white women, Samantha Golden and Amber “Nikki” Elsea, both 19-years old, who were arrested in the victim’s car the morning after he was killed.

Ms. Golden and Ms. Elsea each gave a statement under oath to the Roanoke police on January 13, 2013 describing the events of January 12. Due to the long time between when those statements were given and when Ms. Golden was called to testify at Tyrik’s trial she had forgotten details and reviewed her sworn statement to refresh her memory. Her testimony was consistent with her statement. Ms. Elsea’s was not.

In Ms. Elsea’s statement given January 13, 2013 she stated Mr. Brown asked her to set up a meeting with Mr. Staples. She describes Mr. Brown bragging about shooting him and laughing as he mimicked the way Mr. Staples went limp after he shot him. At Tyrik’s trial, she gave markedly different testimony: Tyrik told her to set up the meeting, Tyrik told her he shot Mr. Staples three times in the back, and Tyrik mimicked and laughed about Mr. Staples going limp. Although the autopsy determined Staples was not shot in the back, and neither woman, nor any other witness, witnessed the actual shooting, the jury took only 13 minutes to find Tyrik guilty of murder. A review of the transcript and full circumstances of the offense makes clear that adults directed this crime.

The judge sentenced Tyrik to 65 years in prison, a sentence that ends in 2078. He will be nearly 80 years old. Limestone Correctional Facility, where he serves this sentence, is awash with the drugs that pervade Alabama’s prisons and the hardest part of Tyrik’s time there is when he runs across people he knows from Randolph County who get high and come around. It takes determination to avoid drugs and violence at Limestone. In the last 12 months, at least five people have been killed there. Limestone’s last warden was arrested on charges of possessing and manufacturing controlled substances. His predecessors were also fired for misconduct.

Earlier this year, Charles Brown died at age 40 while serving a 50-year sentence at Ventress Correctional Facility: He was in the Health Care Unit for evaluation of leg pain when he began having trouble breathing, according to the Department of Corrections. His death is under investigation.

Now 27, Tyrik is back to being the conscientious, diligent student he was before getting pulled into the world of Charles Brown, Rodriquez Staples and the Traveler’s Inn. He’s earned his GED and is working toward an Associate’s Degree. He’s thrown himself into two programs in particular, horticulture and restorative justice; horticulture allows him to create beauty and life amongst the grim walls and cell blocks in prison while restorative justice guides him toward accountability for the harm he caused. His disciplinary record in prison is immaculate, owed in part to being housed in a structured dorm with strict rules and program requirements.

His mother, Tonya Treadwell, is once again proud of her smart, determined son. “It has been incredibly painful to see him in this situation, and I am doing everything I can to support him and advocate for his future. Tyrik is a bright and caring young man who made mistakes early in life, but I truly believe he deserves a second chance. While in prison, he has been working hard to better himself through having a perfect 4.0 GPA at J.F. Ingram State Technical College with multiple certificates and awards.”

Next January, he will be eligible for work release, and is hoping to be approved so he can apply what he’s learned in prison to employment in a community setting. In 2028, he will be eligible for parole for the first time, at age 30. By then, he will have spent more than half his life behind bars.

John Ray Sr. A Life Sentence for Drug Cases Nearly Turned into a Death Sentence for This Veteran. Then A Devoted Son Intervened.

Birmingham, AL – John Ray, Sr. entered prison as a Navy veteran convicted of a nonviolent drug offense, trafficking in methamphetamines. In 2006, he was sentenced to life with parole eligibility. When he came up for parole, like so many Alabamians with parole-eligible life sentences, he was denied.

Birmingham, AL – John Ray, Sr. entered prison as a Navy veteran convicted of a nonviolent drug offense, trafficking in methamphetamines. In 2006, he was sentenced to life with parole eligibility. When he came up for parole, like so many Alabamians with parole-eligible life sentences, he was denied.

“I didn’t want to live any more for a part of my time there,” Mr. Ray said. “I just felt like I was never going to get out. They kept setting me off and setting me off.” He would barely survive the five years awaiting another parole hearing. If not for his son, he probably would not have survived.

Over the course of 19 years in the Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC), Mr. Ray suffered a broken jaw, broken femur, fractured shoulder, and numerous head injuries as a result of assaults. The head trauma caused him to develop a seizure disorder that made continued incarceration in prisons that are riddled with drugs even more dangerous; correctional staff mistook his seizures for the side-effects of drug use and treated him with additional punishment rather than medical care.

Mr. Ray’s most ardent advocate has always been his son, John Ray Jr., who goes by J.C. Ray. A 29-year-old husband and father who lives in Auburn, J.C. spent the last few years of his father’s incarceration caring for his own young family and desperately trying to keep his father alive. The initial parole denial was devastating, as his father’s precarious health only got worse.

“My dad was in the hospital for 11 days, 7 of those on a ventilator, and this evening around 5 p.m. he was taken back to Bullock and placed in a dorm. My dad was severely beaten up by inmates and guards, this was the reason he was taken to the hospital,” J.C. explained in a March, 2024 email, one of numerous emails he sent to ADOC staff, pleading for someone to help his father. Another 2024 email: “My dad is only 11 months from parole and his family dearly wants him to come home. He has a 4 year old grandson he has never got to meet. Over the past 8 to 10 years my dad has had 3 broken jaws, broken ribs, a hernia that was the size of a cantaloupe, a broken femur that a guard at Bullock did to him about a year and a half ago, and now him being on and off a ventilator and put right back into prison population. All of these times he was taken from the prison to an outside hospital. I am willing to share any information I have. He is in severe danger and needs help.”

His concerns were not unfounded. Since 2022, 19 people have died from drug overdoses at Bullock County Correctional Facility. During a single week in April, three incarcerated men, all younger than 50, were found dead in their cells. There were 125 recorded assaults at the prison in fiscal 2024, according to the ADOC monthly statistical report for September 2024.

Through it all, J.C. continued to visit his father and urge him to participate in ADOC’s most intensive drug treatment program, known as “Crime Bill,” which took a full year to complete. Eventually, the younger Mr. Ray contacted Alabama Appleseed, who provided parole representation for his father. Finally, Mr. Ray Sr. was granted parole and released from prison on June 16.

His ordeal, from hardworking veteran to someone who barely survived a life sentence for drug crimes then returned home with major health problems, illustrates Alabama’s dangerously broken criminal punishment bureaucracy. While Mr. Ray completed every drug treatment program offered while he was in prison, access to treatment should not have come with regular beatings and a lifetime of related health struggles.

While still a teenager, Mr. Ray joined the Navy Reserves right after high school, then transitioned to active duty and was assigned to the U.S.S. George Washington, an aircraft carrier. After four years in the U.S. Navy, he returned home to Alabama and fell into drug use. In 1999, he was convicted of Criminal Possession of a Forged Instrument and Possession of a Controlled Substance, both low-level felonies. He served five years in prison. Upon release, he secured employment installing telephone poles. The work was grueling and drug use was rampant among his co-workers. By 2006, he was using again and convicted of this third felony, which resulted in a life sentence under Alabama’s Habitual Felony Offender Act. “I used to do a lot of bad stuff, but I am not the same person,” Mr. Ray explained during a legal visit with us at Bullock County Correctional Facility in preparation for his parole hearing.

Since earning parole, Mr. Ray has settled into transitional housing at Three Hots and a Cot, a Birmingham-area nonprofit that serves veterans. Given his injuries, taking care of his health is a priority. Fortunately, he was accepted into the Birmingham Reentry Alliance. Case manager Stacey Fuller, a veteran herself who overcame substance use disorder, helps him access an array of services in the Birmingham area, provides the transportation he needs to access care and the encouragement he deserves to overcome years of abusive conditions. “This has been awesome because I’m in here with a bunch of vets and we’ve all got something in common,” Mr. Ray said.

“I’ve rarely seen someone so motivated to be successful,” Stacey remarked, as she ticked off a list of VA-provided programs that Mr. Ray is engaged with. “He’s got such an innate sweetness and a desire to do everything he needs to do to overcome his past.” During the last years of his incarceration, he experienced seizures every two to three days. Since his release from the stresses of prison, his seizures have declined.

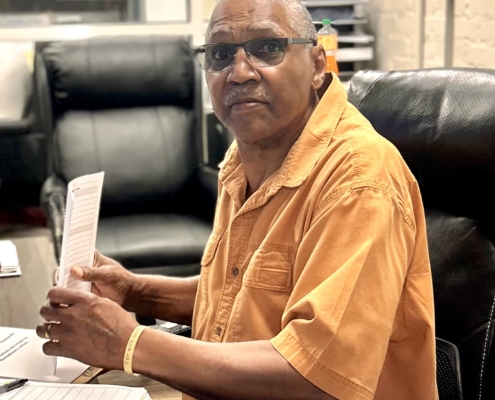

Bennie Haggins saves lives and heals the wounds of addiction. For 33 years, the State considered him a felon in need of supervision.

Birmingham, AL – Bennie Haggins gets emotional when he talks about his longtime Alcoholics Anonymous sponsor who passed away years ago, a man whom he said helped save him from a life of addiction. Even after his death, Mr. Haggins continued going to recovery meetings, because that’s what his sponsor would have wanted. “I made a promise that when he died I’d try and help as many people as I can. I’ve been clean for 27 years. I’ve helped a lot of people get clean and stay clean, too,” Mr. Haggins said.

Birmingham, AL – Bennie Haggins gets emotional when he talks about his longtime Alcoholics Anonymous sponsor who passed away years ago, a man whom he said helped save him from a life of addiction. Even after his death, Mr. Haggins continued going to recovery meetings, because that’s what his sponsor would have wanted. “I made a promise that when he died I’d try and help as many people as I can. I’ve been clean for 27 years. I’ve helped a lot of people get clean and stay clean, too,” Mr. Haggins said.

After a decade in prison, Mr. Haggins was released on parole on June 3, 1991. Now 71, he remained on parole 33 years before finally earning a pardon on October 8, 2025. Only about 30 living Alabamians spent longer on parole than Mr, Haggins, parole records show.

The state maintained control over his movements, despite his decades of selfless, live-saving work. These days, Mr. Haggins works at the Downtown Jimmie Hale Mission, which houses “warming stations” open to the unhoused on freezing nights. Knowing there are so many people whose struggle with mental illness or addiction prevents them from seeking shelter, Mr. Haggins drives the Mission van and seeks out anyone he can save. Countless unhoused Alabamians have lost consciousness on the streets in danger of dying from hypothermia only to be awoken by headlights and Mr. Haggins’ helping hand. Perryn Carroll, executive director at Jimmie Hale, had nothing but praise for his dedication. “He tells me, “don’t you worry, Ms. Perryn, I’ll find them all and bring them in.”’

And yet, Mr. Haggins remained on parole, handing over $40 monthly for state “supervision” based on the 1983 conviction. “I was high and drunk,” Mr. Haggins said of the convenience store robbery 41 years ago that ultimately sent him to prison on a life sentence, a sentence enhanced through the Habitual Felony Offender Act. No one was injured in the robbery that netted him just a few dollars, he said. Previous criminal cases against Mr. Haggins are so old that Alabama’s online court database doesn’t contain documents connected to those charges. Such documents detail what he was alleged to have done and the outcome of each case. Online court records instead only show entries that note his charges. Those entries show he was charged with first-degree robbery in 1983. He had a grand larceny charge in 1977, a separate burglary and grand larceny charge that same year, and another grand larceny charge in 1978. He was charged with theft of property two years later.

Mr. Haggins described his life back then as mired in drugs, surrounded by people who he thought were friends, but who he now knows were not. He’d come to learn he had to distance himself from them if he were to remain drug free and out of prison.

Since his release, Mr. Haggins had just one misstep, early on in his parole, when he failed to check in with his parole officer. That resulted in 90 days of incarceration. Otherwise, his record shows just three minor traffic tickets. “I went to meetings. I got a sponsor. I had to change my life because I didn’t want to go back to my previous normal. I didn’t want to go back to prison, so I just started and kept going,” Mr. Haggins said.

Initially, Mr. Haggins worked at Sterilite Corporation in Birmingham, and remained there until his retirement in 2012. Not content to sit at home, he volunteered at the Salvation Army in Birmingham, where he found he had a gift for working with people who, like him, struggled with addiction. He could speak to them about their problems from a place of understanding and experience, and it made all the difference for them. Eventually, he joined the Salvation Army’s Emergency Disaster Services team that sent him to areas impacted by weather events and natural disasters. “The most important thing was to see the faces of the people when they realized that people cared about them,” Mr. Haggins said.

He spent a decade working at the Salvation Army before taking a job at the Jimmie Hale Mission in 2022 as an intake coordinator, where he continues to help people in need, especially those scooped up on frigid nights. “I always tell them about my life. I’ve found that the more that I say about me, the more you open up about you,” Mr. Haggins said. “They said, if you can do it I can do it too.”

Mr. Haggins wanted a pardon to free him from the need to check in with his parole officer each month, pay $40 monthly in parole fees to the state and restrict his travel without first getting trips approved, but first he had to rectify a case in California that happened when he was in his 20s. An attorney looked into the matter and discovered that a judge in California had signed an order many years ago clearing Mr. Haggins in that matter, but the order was never filed, Mr. Haggins said. It’s since been cleared up, he said. For those who cannot afford access to an attorney, clearing up old matters like that would be next to impossible, almost guaranteeing no likelihood of a pardon.

The process for applying for a pardon in Alabama can be difficult to navigate as well. Mr. Haggins had help, and thought his application had been sent to the proper place and was awaiting Gov. Kay Ivey’s signature for final approval, but the Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles told Appleseed there was no pardon application for him on file. Mr. Haggins worked to rectify his application.

On Oct. 8, 2025, represented by Appleseed attorney Scott Fuqua and supported by Ms. Carroll, Mr. Haggins was finally granted his pardon. He was overwhelmed. “When I look back, I destroyed my whole life, but God blessed me with the opportunity to get it back. I took full advantage of it and tried to help as many people as I could help, and I haven’t stopped.”

REPORT RECOMMENDATIONS

1 Code of Alabama § 15-22-36 (providing authority to grant pardons and remit fines and fees to the Board of Pardons and Paroles.)

2 Executive Budget Office, State General Fund, FY2026 Spreadsheet as Passed Final Act, at https://budget.alabama.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/HB186-Spreadsheet-as-Passed-Final-Act-2025-251.pdf

3 Id.

4 Beth Shelburne, Blood Money: Alabama Department of Corrections pays to settle lawsuits alleging excessive force, Alabama Reflector, May 19, 2025. (“The cost of defending lawsuits against individual officers and larger, class-action cases against the entire department has pushed ADOC’s legal spending over $57 million since 2020. In the last five years, the department has spent over $17 million on the legal defense of accused officers and lawsuit settlements, along with over $39 million litigating a handful of complex cases against ADOC, including a lawsuit filed by the U.S. Department of Justice over prison conditions.”)

5 See SB 60, Sponsored by Sen. Greg Albritton

5 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/smd23003.pdf, 2023, page 8, noting that Medicaid does allow federal funds to pay for qualifying inpatient stays in facilities such as hospitals, nursing homes, and psychiatric residential treatment facilities for durations longer than 24 hours.