Under Pressure

How fines and fees hurt people, undermine public safety,

and drive Alabama’s racial wealth divide

Angela Dabney

Angela Dabney, 40, of Montgomery, is terrified of law enforcement. The single mother of three children, she has three outstanding Failure to Appear warrants for traffic tickets she cannot afford to pay. She says she has never been convicted of a felony or misdemeanor, but she does not have the money to pay her tickets or even afford to keep up with the payment plan she was assigned. Her driver’s license is suspended, and she cannot afford to get it back. Instead, she lives in fear that a chance encounter with law enforcement could upset the impossibly delicate balance of her life.

Dabney desperately wants a job. For a moment, she found one, packing goods for a moving company. But she was fired after a background check revealed her unpaid tickets and suspended license.

The only way Dabney can clear her record is to appear in court and hope that the judge understands her circumstances and either forgives her debt or works with her to create a payment plan she can afford. But if she turned herself in, she risks being locked up until a court date is set.

“I can’t afford to do that. I’m a single parent and I have to be at home with my kids,” she said. Instead, she hides. “[I] can’t get a job because of these tickets. I have to pay my bills or I’d be out on the street, so I take paying my bills over tickets. I’m sorry, it might not sound right, but it’s the truth.”

Jonathan Roberts

Jonathan Roberts acknowledges he’s made mistakes. The 25-year-old, who was living at Mobile’s Waterfront Rescue Mission at the time he was interviewed, became addicted to drugs when he was in his late teens. Over the years, he racked up an estimated $1,700 in court fines and fees – debt that nearly doubled, he said, due to his inability to pay on the schedule set by the state. He’s lost his driver’s license and, with it, his ability to work. On numerous occasions, he’s lost his liberty because of his inability to get to court for dates that keep being reset. He hasn’t quite lost hope – not yet.

“[E]very time I’ve missed a payment, they either put a 35% fee on it because I missed a payment, or they put me in jail. There was one time I spent two months in jail and only got $750 off,” Roberts said.

Sometimes, Roberts’ court date would be reset, forcing him to travel long distances from his then-home near Mississippi at a time when he had no driver’s license or money to help pay for gas, even when he could get a ride. Missed court dates led to Failure to Appear warrants that put him at risk of being dragged back to jail any time he came into contact with law enforcement.

“Say I was driving without a driver’s license. … So if I get pulled over, I get a [citation for] driving while suspended. It just racks ups, racks up, racks up and just gets higher and higher and higher. And before you know it you’re just in an overload of debt, and every time you get pulled over, every time you’re riding in a car with somebody, you’re just going to jail,” he said.

Mobile’s District Attorney Restitution Recovery Team (DART), which receives referrals for uncollected court debt and is empowered to collect a percentage off the top of anything it takes in, even came after Roberts while he was in a drug rehabilitation center trying to get his life back together.

“They’re threatening to put warrants on me because I can’t afford to pay while I’m in a rehabilitation center,” he said. “Every time I turn around, they got a warrant out because I can’t pay. Even if I pay like $5 or $10, they still take 35 percent of that, so you pay $10, you’re really only paying $6.50. They said it’s a one-time fee, but if you have a couple different cases in a couple different things, they just stack up.”

Sober for 14 months, Roberts is eager to get his life back on track. He tried community service when it was offered, but received only $50 off his debt for eight hours of labor – less than minimum wage. He wants to work, but despite training as a diesel engineer and a job offer from his father, who owns and operates tugboats, he can’t get an occupational license because his driver’s license is suspended.

“Without a driver’s license, you can’t get a boat license. I’m working on getting my captain’s license, and I’m at the bottom stage because of my court proceedings. And that’s where I’m stuck at right now,” he said.

“I know I messed up when I was young, but let’s try to move forward,” he continued. “Because if not, being in debt, it makes the bad side so much easier than the good side. And if you want to stay to the good side, you need a little help. Just a little. A pat on the shoulder, or just ‘We’re not gonna put you in jail this time because you can’t pay. But having to fear the police is not right, because of debt.”

Callie Johnson

Callie Johnson doesn’t have any outstanding legal debt. But it’s not herself she’s worried about – it’s her adult children. Johnson, 55, of Montgomery, estimates she’s spent over $2,000 dollars helping two sons and two daughters pay off court debt over the years.

Callie Johnson doesn’t have any outstanding legal debt. But it’s not herself she’s worried about – it’s her adult children. Johnson, 55, of Montgomery, estimates she’s spent over $2,000 dollars helping two sons and two daughters pay off court debt over the years.

One of her sons died in 2016 at the age of 27. He was intellectually disabled and suffered from seizures and serious mental illness. More times than Johnson can remember, he was arrested and jailed for criminal mischief after restaurants or other business establishments called the police because they did not like having him on their premises.

“Every time, criminal mischief – but how? He was just sitting over there,” she said. “And I know if they tell him to move – and a lot of them don’t understand. When you have those mentally challenged people, if you holler at them, oh my goodness, that just sets them off, and they don’t understand. Every police officer needs to have a degree in psychology.”

Few police officers have a background in psychology. Nor do many jail officials, who would worry Johnson to death by housing her disabled son with the general population instead of in a medical cell. No judge in her memory dismissed charges against him, even after she brought attention to his multiple disabilities and difficulty following directions or understanding why his behavior might be considered objectionable. So over and over, she bailed him out and helped pay off debt.

Another son also struggled. His car was old and conspicuous, and the same police officers pulled him over again and again, ticketing him for driving without a license or insurance. He once spent about two months in Montgomery City Jail due to unpaid tickets. At 36, he just got his license reinstated after more than a decade without one.

Two of Johnson’s daughters also have substantial debt to pay off from tickets for driving with suspended licenses or without insurance. One of them is on a payment plan. The other is afraid to go to court – she has three children, and cannot afford to go to jail, pay her tickets, or buy insurance.

Johnson struggles to keep herself insured. She has a job, but between rent and other necessities, and keeping her struggling children afloat, she can only afford insurance off and on. Describing her children’s situation – and her own – she said, “You have to have insurance to get a tag. … But they don’t go back and finish paying because they don’t have the money. They just need to get transportation. So it’s all a Catch-22.”

Betty Lou Wilson

Betty Lou Wilson sees no end in sight. The 62-year-old Montgomery woman, who completed her sentence almost a decade ago, owes the state several thousand dollars in court costs, fines, and fees.

Wilson works as a housekeeper at a Montgomery office supply manufacturer. She has no vehicle. Her driver’s license is suspended, and she cannot afford to get it reinstated. She pays $100 a week to stay with a friend, who charges another $30 a week to drive her to and from work.

For five years after her release from prison 2009, Wilson paid $40 a month to a probation officer who told her he didn’t care where her money came from just so long as she got it to him on time. When she was out of work, she covered probation and other costs with high-interest loans from payday lenders, who raided her checking account as soon as she deposited any money.

Wilson doesn’t use banks anymore. Instead, she pays $5.00 a month for a Wal-Mart card. She swipes it once a week to get the cash she needs for living expenses, at a price of $2.75 a swipe, because she cannot afford to get to a Wal-Mart to swipe it for free. The day she was interviewed for this report, she had $22.00 on hand to get through the five days until a court date where a judge would ask her why she was behind on paying her court debt.

“I don’t have anything. Nothing.” Wilson said. “I did every day of my time. I walked all my probation down. … If we set up a payment plan, what can I pay you? I can’t pay you anything because I don’t have anything.”

“What can I do?” she said. “You can’t get blood from a turnip.”

Rhonda Faye Mitchell

Rhonda Faye Mitchell did everything right after getting out of prison. She found a place to stay, she landed a salaried position as a housekeeper at a Montgomery church, and she set out to put her life back together.

Mitchell, 43, earns about $1,200 a month as housekeeper at a church near the halfway house she currently calls home – but she can’t cash her paycheck. Without a driver’s license or other valid ID, she can’t open a bank account or even use a check-cashing service. It’s a good thing she can walk to work, because it could be a long time before she’s able to retrieve her license.

Mitchell was preparing to take her test and pay her reinstatement fee, when a state worker told her that there was a bench warrant out for her arrest for failure to appear on a ticket she received sometime between 1999 and 2002, which resulted in the suspension of the Tennessee license she held at the time. Mitchell tried to find out more, but without her Tennessee driver’s license number, which she does not remember, she can’t even learn what exactly she owes or what sentence she faces for this long-ago violation. Her only option is to go to court in Brookside, Ala., the tiny Jefferson County town from which she was told the warrant issued.

The problem is that if she went to court in Brookside, she would be arrested and jailed because of the outstanding warrant. The same fate would await her if she tried to get the felon ID which the state of Alabama issues to qualifying individuals after their release from incarceration. Until she resolves things, Mitchell, who owes about $600 in restitution plus $40 per month in probation fees, will keep walking to work.

“I wanted to be able to go ahead and just – what is it that I need to pay, what is it that I need to do?” she said.

“[W]hat I’m facing now is not really being able to go handle it myself for fear of being locked back up in a county [jail],” she said. “I just got this new job. I cannot afford to not be at work.”

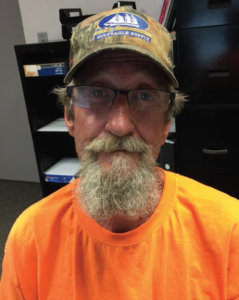

Robert Stanley

Robert Stanley was six months out of prison and doing well. He had a job in construction. He had a life. Following the conventions of small-town life in rural Alabama, he waved to police officers when he saw them.

Then he got caught up in a roadblock. Police ran his name and found he had an outstanding warrant for failing to appear at a court date regarding his failure to pay court debt.

Stanley, 31, hadn’t known about the court date, and in any case, he was locked up in prison at the time it took place. It would have been impossible for him to attend.

None of that mattered to the police who arrested him and took him to jail. “They said it wasn’t their problem,” he said.

On top of the debt, Stanley was assessed a $750 “DA fee” for his failure to pay. He doesn’t know what a DA fee is, but he does know “I stayed in jail two weeks and had to pay that before I could get released. I had to borrow it from in jail, I had to get my family to work on it,” he said.

Paying them back when he got out was a problem too. “I was working, but I didn’t have no employment after that because I had missed two weeks,” he said. “I just kind of lost hope. I said screw it, you can’t win for losing. Even if you’re trying to do right.” He relapsed and was soon facing additional drug charges in another county.

He returned to prison and completed two eight-week drug rehab courses, hoping those would fulfill an element of his plea agreement that required him to enroll in residential rehabilitation upon release. Stanley’s four months in Alabama Department of Corrections-certified rehabilitation did not count toward his plea agreement, though, so off to residential treatment he went. He owes close to $10,000 in court debt. Some of those payments are officially on hold while he completes treatment; he’s accumulating interest and penalties on others. He expects to owe $300 a month in fines, court costs, and reporting fees once he starts paying again.

“It’s hard to get back going,” he said. “It’s so much pressure on a person.”

Teon Smith

Teon Smith, 41, thought she was doing the best thing for her family when she took out $50,000 in loans to go back to school at a private, for-profit college in Montgomery. A single mother of five, she thought an associate degree in business would help her get the kind of job she needed to support her children, who range in age from 5 to 15.

Smith has signed up with temp services, registered at career centers, applied, interviewed – and been turned down because most professional jobs require a valid driver’s license. Smith doesn’t have one because of $1,400 in traffic tickets in two counties.

She tried. She gave up necessities, but her monthly grocery bills run $150 to $200. She took out a $300 payday loan to try to stay current on the payment plans, but she fell behind in Elmore County. After that, the judge told her she needed to pay in full or not at all. Since Smith doesn’t have $1,400 dollars, her license is suspended.

“They don’t care. You get a ticket, you go to court, if you don’t, you go to jail. And then if you can’t pay it … they don’t even try to work with you,” she said.

To try to pay the bills, Smith works at retail job for $10.00 an hour, but some weeks she doesn’t even get 12 hours there. She’s terrified every time she gets in the car to drive to work, but the alternative is worse.

“We run out of food, for real. … I have four boys and they can eat,” Smith said. “If I had a cow, I’d be happy, because they drink milk like that in my house. Two gallons don’t last a week.”

Terrence Truitt

Terrence Truitt’s teenaged twins are always hungry. But the 38-year-old Montgomery man doesn’t always have the cash he needs to feed them. To keep food on the table, he fishes.

Truitt knows from experience that he won’t catch much at local pay-to-fish ponds. So when he needs food, he fishes where he knows he’ll get what he needs, even if that means fishing on public land where it is forbidden. On several occasions, encounters with game wardens have resulted in significant fines: $200 if he pays right away; $600 when he’s forced to go to court. Between court costs associated with his fishing violations, traffic tickets, and debt from a conviction for possession of marijuana, Truitt says he owes more than $5,000.

In the past, Truitt has been jailed for his inability to pay. His probation for the marijuana conviction was extended to two years because he couldn’t pay off all he owed before then. He’s borrowed from family and friends, accepted charity, and taken out predatory loans in order to pay off court fines and fees. He’s been jailed for failure to pay. He pays what he can, when he can – but always by mail, because he’s afraid that appearing in court will result in his incarceration on failure to appear or failure to pay warrants.

Truitt, who was homeless but had recently found a steady job when he was interviewed in June 2018, says his main concerns are finding enough food for his children and scraping together money to pay his court debt.

“It’s kind of hard from time to time,” he said. “I be trying to feed their mouths the best I can without getting into trouble. So I just do the fishing.”

Terry

Terry pays $275 a week for the Huntsville motel room he shares with his three adult children and two school-aged grandchildren. They’d like to move out and find a place where the children and their mother, was seven months pregnant at the time Terry was interviewed, would have stability and enough space, but there’s nothing affordable within walking distance of Terry’s job.

Terry, 57, doesn’t have a car. Even if he did, it would be risky to get on the road because his driver’s license is suspended, and he can’t afford the fee to get it back. Between back child support payments and a 20-year-old criminal justice debt that he estimates has increased by about $400 since he incurred it two decades about, Terry, who makes $12 an hour, owes the state about $3,000.

The three adults living with him, ranging from ages 21 to 27, are in similar straits. At the time he was interviewed, Terry was helping one of his daughters pay the state $75 a month on a fine she received for driving without insurance. Her license was suspended after she missed a court date, so he was also putting money aside for the $150 she’d need to get it back.

A wounded veteran, Terry is eligible for housing assistance from the U.S. Department of Veterans’ Affairs. He has refused it because his adult children would not be allowed to live with him. For a while, he and his family lived in a home in Ardmore, within walking distance of a job where he made $16 an hour. But his supervisor, who was friendly with the landlord, moved in uninvited and started making unwanted sexual advances on Terry’s pregnant daughter.

Terry kicked him out, and two days later, the whole family was evicted. “They locked my daughter out and throwed all of her stuff away,” Terry said. “My granddaughter and grandson lost everything that they had – clothes, toys.”

The family moved into a motel room, where the four adults and two children have just two double beds between them. They get food assistance from a local food pantry, but “just don’t have a lot to cook with out there – we’ve got one skillet,” said Terry. They have no vehicle. Last school year, the children missed so much school that their mother feared they’d be taken from her.

“All I want to do – I want to live peacefully, and I’d like to have a place to live. But there again, I have to take care of my grandkids and my daughters. They’ve made their mistakes, but they shouldn’t have to keep paying for them,” Terry said. “I pray for them every day. All I want is for them to be all right. All I want is a home to where they don’t have to worry where they’re going to go.”