By Eddie Burkhalter, Appleseed Researcher

More people died in Alabama prisons per capita than in any state in the nation in 2024, and at a rate that was nearly double those of the next highest state. In 2023 Alabama’s prison death total was even higher.

Alabama prison’s mortality rate in 2024 was 101.81 per 100,000 incarcerated people, when 277 people died inside our prisons. The next highest state was Georgia, where the prison death toll reached 65.29 deaths per 100,000, according to UCLA School of Law’s Behind the Bars Data Project, which collects such data nationwide.

Alabama’s prison deaths reached a record high in 2023, when 327 people died, which came to 122.7 deaths per 100,000. That was far higher than even the second highest state, Vermont, which saw 75.08 deaths per 100,000 that year.

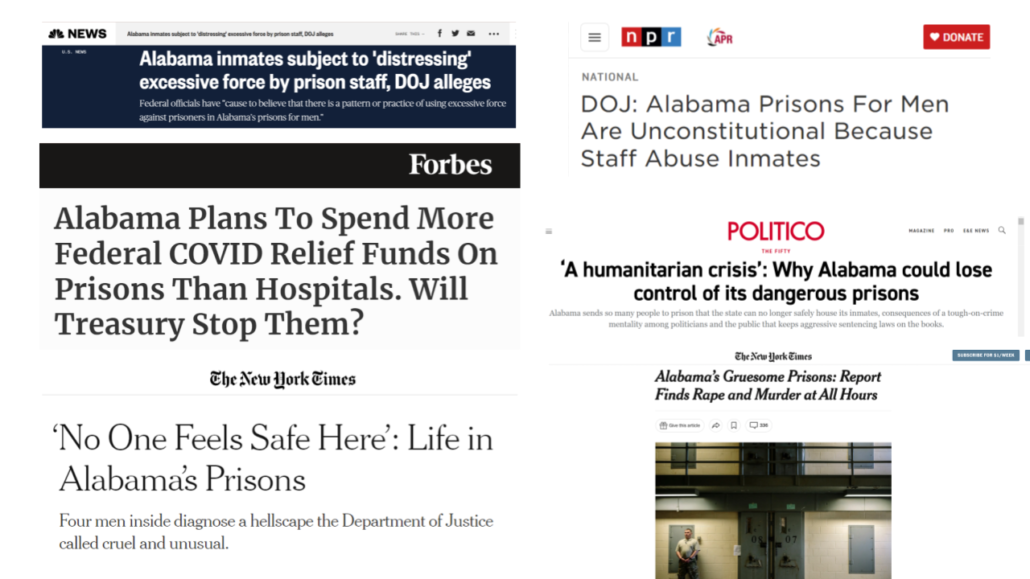

National and international reporting on the human rights crisis inside Alabama prisons has cast a shameful light on Alabama state government and its failure to remedy these problems after years of knowledge.

Alabama Appleseed’s own project to track and publish state prison deaths began in 2024 and the initial batch of data we have collected has been included in UCLA Law’s data. (Individual-level data on Alabama prison deaths in 2024 can be found by visiting UCLA Law’s Github site and navigating to the raw data for Alabama. The project will soon add Appleseed’s 2022 data to the site.)

Prior to UCLA Law’s project, journalists, researchers and the public were left with incomplete data, sporadically released by the federal government under the federal Deaths in Custody Reporting Act. Federal policy changes since 2019 have made that data less accurate, so Appleseed’s own research is helping shed light into the details of how so many people are dying inside Alabama prisons, which we hope will help lead to the systemic changes needed to save lives.

Database of Alabama prison deaths

Filmmakers with the documentary “The Alabama Solution”, which highlights the plights of incarcerated men in Alabama fighting against their unconstitutional mistreatment, also built a database of Alabama prison deaths, which include deaths that occurred during the years 2019-2024. The film is garnering worldwide attention and is helping spread awareness about Alabama’s broken prison system.

Those filmmakers also note issues in gathering detailed data on Alabama prison deaths, which include a large reduction in the number of autopsies for those who die inside Alabama prisons since May 2024. The Alabama Department of Corrections since then only seeks autopsies for “deaths resulting from unlawful, suspicious or unnatural causes” which leaves suspected overdose deaths and those who died from suspected natural causes and other unknown causes, without receiving full autopsies. Appleseed first reported this change in autopsy procedures in May 2024.

It’s critically important to the families of those who died in custody, and to the public, to understand why these deaths are occurring, and when they were preventable.

Aaron Littman, assistant professor of law at UCLA School of Law, deputy director of the UCLA Law Behind Bars Data Project and faculty director of the law school’s Prisoners’ Rights Clinic explained it this way: “There is a national crisis of failure to report and understand deaths in custody, and the importance of that really can’t be overstated,” Mr. Littman said. “These deaths are happening out of public view, and in institutions that have total control over people’s access to information, access to medical care, institutions that are often plagued by violence, and often access to illegal substances.”

Lack of transparency by ADOC

An additional barrier to the data remains a lack of transparency from ADOC around prison death reporting. A 2021 state law requires the department to publish a quarterly report containing statistical data on the number, manner, and cause of inmate deaths occurring in prisons “including the results of any autopsy provided to the department by a third party.” ADOC began including a section labeled “Final autopsy results” in those reports. However, without stating a reason, the department removed that section from the reports beginning with the last quarterly report in 2022, despite the reports still containing the phrase that “the final autopsy results reflect the opinion of the medical examiner conducting the autopsy of the final cause of death.”

The lack of transparency surrounding these deaths is all the more alarming given ADOC and the state’s legal battle over the unconstitutional treatment of incarcerated men. The U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division in 2019 released its first report detailing the out-of-control prisons for men in Alabama, The federal government in December 2020 sued the state and ADOC alleging widespread use of force, corruption, rampant drugs and contraband, and the inability of ADOC to keep men safe from sexual and physical violence and death.

During President Donald Trump’s second term there has been a mass exodus of staffers from the DOJ’s Civil Rights Division, which is investigating and prosecuting Alabama’s case, leaving concern that the DOJ’s case could be jeopardized. All parties in the lawsuit are currently in mediation, according to court records. An October 3, 2025, filing from the judge in the case states that “Despite the Government shutdown, the parties are ORDERED to continue their ongoing mediation efforts, including attending the mediation scheduled next week before Judge Ott. Signed by Judge R David Proctor on 10/03/2025.”

UCLA Law’s prison death data is a valuable resource but the data has limitations, however. Not all states report prison deaths publicly or to the federal government, and there were discrepancies between some state’s own records and what the states sent to the federal government. That’s a problem Appleseed’s own research into these deaths discovered, so we compared data from several state and federal agencies, as well as news accounts and deaths collected by advocates, to get a fuller picture of who is dying and why.

An “awfully low” number of people in drug treatment

Appleseed thus far has finalized its death records for the years 2023 and 2022, and is working to collect data that will eventually cover the decade between 2014 and 2024. The picture already emerging is one of uncontrolled overdose deaths, unchecked violence and large numbers of deaths caused by illnesses in younger people, pointing to the possibility of substandard medical care.

Drugs are prevalent inside Alabama’s prisons, and are the major driving factor in violence and death throughout the state’s 14 major prisons. Alabama prison’s overdose mortality rate in 2023 was 20 times higher than the national average across all state prisons in 2019, the last year for which the federal government has made that data available. Illicit drugs are most often brought in and sold by Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) staff themselves, as publicized arrests and interviews with incarcerated people show, and while ADOC has made increasing efforts in recent months to catch and charge these employees, drugs and the overdose deaths persist.

Despite the prevalence of drugs inside Alabama’s prisons, very few incarcerated people are receiving medically-assisted drug treatment while incarcerated. Members of Alabama Legislature’s Oversight Commission on Alabama Opioid Settlement Funds met in October and applauded the state’s more than 30 percent drop in drug overdoses.

During that October meeting lawmakers on the commission heard from ADOC’s Deborah Crook, Deputy Commissioner of Health Services, who spoke on the department’s use of opioid settlement funds to launch the department’s Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) program in 2024, to provide evidence-based addiction treatment inside the state’s prisons.

“Financially, we haven’t used all of the money allocated,” Crook told the commission. ADOC has served 500 incarcerated people in the MAT program and at the time had 256 people in treatment.

Crook was asked by a Commission member Sen. Larry Stutts. R-Tuscumbia, what percentage of Alabama’s incarcerated population has a substance abuse disorder, and while she didn’t have Alabama-specific data, she said that nationally the figure is approximately 60 percent of incarcerated people in state prisons.

Sen. Stutts noted the low percentage of incarcerated people receiving treatment, saying that if even half of the state’s then-just more than 21,000 incarcerated people were battling addiction “and only 250 are in a treatment program…that just seems like an awfully low number.”

ADOC Commissioner John Hamm told the commission member that MAT treatment is “voluntary” and that the department is working to drive more into treatment. Crook said that while the number of participants in MAT was low, thousands more were in other non-medication assisted treatment programs. While this may be true, the waiting list for those other drug treatment programs can be months long, and the programs themselves are lacking, according to Appleseed’s discussions with incarcerated people and their families.

The prevalence of drugs inside Alabama’s prisons is also driving large numbers of assaults and homicides.

In 2023 there were 14 homicides in Alabama prisons, which translates to 67 per 100,000 incarcerated people. The UCLA data doesn’t show causes of death for the second highest death rate state that year, but does for Tennessee, the third highest, a state that saw 6 homicides in 2023, translating to 24 per 100,000.

ADOC hasn’t yet completed death investigations for all who died in 2024, but so far the data shows there were at least 12 homicides that year, double that of homicides in Tennessee prisons last year.

Families left behind to grieve

Deandre Roney died June 9, 2024, after being stabbed at Donaldson Prison.

These failures are not confined behind prison walls. They impact the families left behind, like the Roneys from Birmingham. Deandre Roney’s family begged ADOC to keep him safe. Just five months before his scheduled release date of Nov. 6, 2024, Mr. Roney was stabbed in his back and in his head at Donaldson Prison by a makeshift knife and died June 9 at UAB Hospital. Chante Roney, Deandre’s sister, told Appleseed last year that the day before he was attacked he asked officers to move him to another dorm because a man had been chasing him with a knife.

“He was reaching out, uneasy. He didn’t feel safe. He felt like something was going to happen before he made it home by November, and they failed him. They really failed him,” Ms. Roney said.

Mr. Roney was one of four men killed in Alabama prisons during the month of June last year.

“We were saving money up for him to come home, to buy him clothes, because he’s been gone all these years,” Ms. Roney said. “He was coming home the first week of November, His birthday was at the end of November, and he didn’t even make it.” Instead of using that money to help her brother make a life outside of prison, the family used it to bury him.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!