The worsening toll of Stage 4 cancer in an Alabama prison.

This is a follow up to our first story on Ronnie Peoples in Appleseed’s series “Cruel and Unusual” focusing on the people harmed by Alabama’s overreliance on excessive sentences, which trap people in deadly, dysfunctional prisons long after they have paid their debt.

By Eddie Burkhalter, Appleseed Researcher

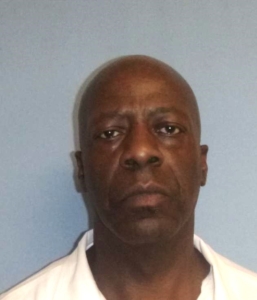

It’s been six months since Ronnie Peoples was diagnosed with stage 4 prostate cancer, and he worries – from deep inside St. Clair prison – that he still doesn’t know if the treatments are working, or if the cancer has spread more into his ribs and lungs, where doctors found it months ago.

Getting timely medical information on his condition while serving time in an Alabama prison is difficult, Peoples explained to Appleseed. One recent slip-up by a well-intentioned but overworked nurse in St. Clair resulted in a missed opportunity to get critical lab work needed, putting him another week behind in learning whether the cancer is receding or spreading, he said.

“You’ve got to have someone on the outside,” Peoples said, referring to a friend from out of state who called the Alabama Department of Corrections, which resulted in medical staff ordering that lab work be done at Brookwood Baptist Medical Center.

Ronnie Peoples

He received a second injection of a chemotherapy drug on October 10th, which treats his disease for three months, but the disease is taking a toll on him, both physically and mentally. “It’s been touch and go,” Mr. Peoples said when asked how he’s holding up. Pain is worsening, and he’s now suffering from shortness of breath. “I’m a fast walker. Now, I have to slow down. It’s hardest on stairs.”

Mr. Peoples is 68 and has served 32 years of a life without the possibility of parole sentence under the state’s Habitual Felony Offender Act (HFOA). He is among the growing number of very sick and older incarcerated people in Alabama with lengthy sentences and no clear pathway for release.

Mr. Peoples received his life without the possibility of parole sentence after a 1991 robbery at a beverage company conviction in Tuscaloosa County. No one was injured. His sentence was enhanced under the HFOA because of prior robbery convictions more than four decades ago in the 1970s, including in Ohio. Life without parole was the only available sentence at the time, but because of changes to Alabama sentencing laws, Mr. Peoples would have been eligible for a much shorter sentence if current laws applied to his case.

The day after Mr. Peoples had his lab work done he planned to return to the job he’s had for more than two decades, keeping track of the tools used in the welding classes in St. Clair prison’s trade school. He’s known Bradley Black, the welding instructor at St. Clair prison, since Mr. Black began working there in the early 2000s. “His church prays for me every night,” Mr. Peoples said.

In 2015, Mr. Black wrote a letter to a judge on Mr. People’s behalf. Mr. Peoples sought resentencing, but was unsuccessful despite support from people who knew he had been rehabilitated..

While speaking to Appleseed, Mr. Peoples said he was in pain, but that he couldn’t get his twice-daily pain medication dosage increased because the company that oversees healthcare in Alabama prisons, YesCare, has to approve all medication changes and medical procedures. The doctor at St. Clair prison told Mr. Peoples that he could ask for a dosage increase, but said “they’re going to deny you, and cuss me out,” Mr. Peoples said the doctor told him recently.

The Tennessee-based private equity-owned company YesCare was formerly known as Corizon Health, but in 2021 the company was split into two separate entities, according to a report published in October 2023 by the nonprofit Private Equity Stakeholder Project. YesCare retained much of the same staff as Corizon Health and the company’s prison contracts, while Tehum was saddled with the company’s debt. In February 2023, Tehum filed for bankruptcy. Thousands of lawsuits against Corizon Health in previous years alleged medical neglect and the deaths of incarcerated people, and the mounting debt from those lawsuits across the U.S. preceded the split, which allowed the company to continue operating as YesCare while leaving the debt with Tehum, the report details.

“Tehum, the bankrupt new company created in the maneuver, owes more than $82 million to over 1,000 creditors, including former patients who were injured or neglected, former employees who were hurt on the job, hospitals, doctors’ offices, cities and states,” The Marshall Project reported.

YesCare, meanwhile, got an enormous boost from the State of Alabama. The Alabama Department of Corrections in February 2023 approved a contract worth more than $1 billion with YesCare to provide healthcare in the state’s prisons.

The Private Equity Stakeholder Project report also details the company’s troubling past, and difficulty holding on to valuable contracts. “In the three years up to 2015, it lost contracts in Minnesota, Maine, Maryland, Tennessee, and Pennsylvania.” In late 2015, the company announced it would end its Florida contract early because the agreement was “too constraining,” the report states. “Patient deaths in the state had spiked to a 10-year high shortly after Corizon took over its prison healthcare services.”

The report notes that in subsequent years Corizon lost contracts with New York City and a $188.6 million contract with the state of Arizona “after allegations of serious medical neglect.” The contract’s “per inmate day” rate “created an almost irresistible incentive to deny care,” according to the director of the ACLU National Prison Project.

“In 2021, Corizon lost its contract with the Idaho Department of Correction, and also lost a $1.4 billion bid to provide healthcare services in Missouri, where it had provided prison healthcare since 1992,” the report reads.

As he awaits word as to whether his cancer has spread, Mr Peoples is also dealing with a loss of appetite caused by his treatments. “Sometimes when I smell the food I can’t eat it. It makes me nauseous,” Mr. People said.

The pain is constantly increasing, his appetite is waning and he often loses his breath, but Mr. Peoples said he’s still hopeful that he’ll be cured and some day be freed from prison.

He wants to be free again, to spend time with his sons and grandchildren and to work on the outside.

“First thing I’d need is my drivers license back,” Mr. Peoples said. “Got to have that if I want to work.”

But for now, Mr. Peoples waits for word on his cancer, and will go back to his work station at the prison’s trade school where Mr. Black has trusted him for more than two decades to take care of the tools that he carefully tracks.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!