By Leah Nelson, Appleseed Researcher

WOODLAND, Ala. (March 30, 2019) Teresa Almond is terrified. Though more than 13 months have passed since the day the Randolph County Drug Task Force upended her life with a flashbang grenade and a raid on her home, the 49-year-old grandmother still spends at least part of most days sitting beneath the shelter of a relative’s carport, clutching a firearm and waiting fearfully for the deputies to come back.

Across the street is the house where she and her husband Greg Almond raised their children, where they celebrated holidays and birthdays and weekends with grandchildren, from 1991 until January 31, 2018. That day, after a sheriff’s deputy said he smelled marijuana at the house, the drug task force broke down the Almonds’ door, detonated a flashbang grenade, forced the couple to the floor at gunpoint, and tore through the house.

The task force found about $50 worth of marijuana and a single pill of Lunesta, a prescription sleep aid, that was outside of the bottle bearing Greg’s name and showing it was his prescription.

On this pretext, task force members handcuffed the Almonds and booked them into the Randolph County jail. They were charged with possession of marijuana in the second degree, a misdemeanor, and with felony possession of a controlled substance because the Lunesta pill was not in its original packaging.

Greg’s family watched from their home across the street as officers remained at the house till past dark that night, carting out tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of belongings: Greg’s sizable gun collection, a chainsaw, a weed eater, antique guitars, a coin collection, Teresa’s wedding rings, and about $8,000 in cash the Almonds kept in safes in the back of the house. The doors were left unsecured; the Almonds’ dog escaped. Greg and Teresa, neither of whom had ever been arrested before, spent the night in jail.

Drug task forces undertake raids like this one with some frequency in Alabama. They are joint operations of county, municipal, state, and sometimes federal law enforcement agencies. They often work off tips from confidential informants and seek to surprise drug manufacturers and shut down illegal activity. Sometimes, they take property and assets as evidence.

They are also permitted to seize items under a process called civil asset forfeiture, which enables the state to take and keep cash, vehicles, valuables, and even real property if they are able to prove to the “reasonable satisfaction” of a judge that it is the fruit of, or was used to facilitate, illegal activity.

Civil asset forfeiture can be enormously profitable for the state. Historically, Alabama has not tracked or made public income from forfeitures, though this will change if prosecutors follow through on a recent promise to create a public database. But in 2018, the Alabama Appleseed Center for Law and Justice and the Southern Poverty Law Center examined about 70 percent of civil asset forfeiture cases filed in 2015, in a first-of-its-kind effort to quantify the results of this practice. The resulting report showed that Alabama raked in nearly $2.2 million in 827 disposed cases in 2015. That same year, courts awarded law enforcement agencies 406 weapons, 119 vehicles, 95 electronic items and 274 miscellaneous items, including gambling devices, digital scales, power tools, houses, and mobile homes.

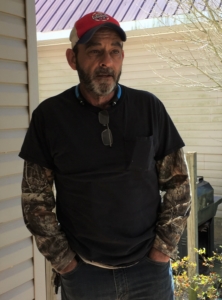

Greg Almond looks over the remains of his home after the raid.

In 18 percent of 2015 cases where criminal charges were filed, the charge was simple possession of marijuana and/or paraphernalia, crimes that by definition do not enrich the people who commit them. Possession of marijuana in the second degree was the only charge against the Almonds that stuck after a grand jury rejected the notion that possession of Lunesta for which Greg had a valid prescription constituted a felony.

The Almonds say their adult son, who was living with them at the time, told law enforcement that the marijuana was his and that his parents did not know it was in the house. But the prosecutor declined to drop the charges. The Almonds expect to go to trial in Randolph County Circuit Court soon.

In the meantime, they have filed a federal lawsuit alleging civil rights violations by the county, the county commission, and several sheriff’s deputies. Among other things, the suit alleges that the sheriff did not even follow proper procedure for undertaking a civil asset forfeiture. Under current law, the state must file a civil suit and make a showing that there is a meaningful connection between the assets seized and criminal activity, and a judge must agree that that is so. But according to the Almonds’ lawsuit, Randolph County law enforcement never filed such a suit. They simply kept the Almonds’ things, depositing the cash they’d taken into the general fund of the Randolph County Commission. The suit also alleges the task force failed to correctly log many of the items they took, including about half the cash, half the guns, and other items and valuables. The task force simply took them. And now the Almonds have nothing.

Todd Brown, an attorney representing the county, the county commission, and all but two of the individuals named as defendants, declined to comment, citing ongoing litigation.

From the Almonds’ perspective, the task force’s timing could not have been worse. At the time, the Almonds’ primary source of income was Almond Memorial Monument Company, a family-owned tombstone-engraving business that Greg inherited from his father and operated with their son. To save for retirement, the Almonds also operated chicken houses, feeding and sheltering birds until they were ready for slaughter and processing. Teresa sometimes cleaned houses to earn extra money as well.

In 2017, the poultry producer with whom the Almonds were contracting told them they could not house any more birds until they made some changes to their chicken houses. Money was tight that year, as Greg sought to earn extra from his monument business to re-invest in the chicken houses. The Almonds lived on land that had been in Greg’s family since 1901, but had mortgaged a portion of their property, including their house, to start up the chicken farm. They were due to sign paperwork restructuring their loans on Feb. 1, 2018, at 10 A.M.

They missed that deadline because they were in jail. The night the Almonds were locked up, Greg’s sister was 30 miles away staying with their mother, who had been hospitalized. She bonded Greg and Teresa out the next day, and they rushed to the bank. They got there too late, and once the deadline passed, the opportunity to restructure fell through. They lost their house, and much of Greg’s family land.

The raid and the loss of the $8,000 had an outsize effect on the Almonds’ financial circumstances. It interrupted the careful flow of resources that kept their small business afloat and undermined their options for renewed consideration for loan restructuring after they missed the bank deadline because they were in jail.

The raid had other repercussions. The Almonds’ arrest was big news in their rural community, where lawns are punctuated by “Back the Blue” signs indicating residents’ support for law enforcement. When the Almonds went to jail, rumors started that they operated a meth lab, that they were drug dealers or manufacturers or worse. Greg’s mugshot appeared on the sheriff’s Facebook page. People whispered, and business dwindled. Greg’s reputation as a businessman, carefully cultivated over decades and attested to in older posts on the Almond Monument Memorials Facebook page, evaporated.

Greg, who between the monument business and chicken houses used to work 16-hour days, found work as a handyman. His boss treats him well, but he is lucky if he brings home $95 a day. “If somebody came up to me right now and said, ‘Here, here’s $15,000, so you can start your business back up,’ I couldn’t because my shop is full of our furniture. That’s the only place I had to put it,” he said. “I’m in worse shape than when I was 17 years old because at that point, I didn’t have bad credit, I just didn’t really have no credit. Now with this, I have poor credit, and I might have a little more than I did when I was 17, but not much. And now at 50, I have bad knees, I can’t get out there and get it like I used to.”

Greg stayed in their house until the bank forced him out. Teresa came back once, saw the piles of toys and Christmas decorations and mason jars of home-canned vegetables the task force had strewn around her home, and never returned. Since May 2018, the closest thing the Almonds have had to a home is a storage shed the size of a vacation camper-trailer that they previously used to store catfish feed and fishing rods.

Christmas gifts and toys left behind after the task force raid

Greg insulated the shed, but the Almonds have no running water or indoor plumbing. They cook over an open fire outside their front door and keep food cool in a portable cooler. A small solar panel provides enough electricity to power their television and a floor lamp at night, but they do not have enough power to run an air conditioner. For Christmas, Greg’s boss gave them a wood-burning stove to supplement the propane heater they had been using. Some mornings, Greg wakes up to indoor temperatures in the low 50s.

Teresa, who is restless and fearful and speaks so quietly it’s hard to hear her at times, rarely stays in the shed. “I’m not right. I have not been right since the day it happened,” she said.

“That was my home. I raised all my babies in there. And my grandbabies. If my grandbabies would have been there that day, they would have hurt my grandbabies,” she continued. “I have nowhere to bring my babies to spend time with them. Cause this is not a atmosphere that I want my grandbabies in, and them remembering that we lived in a shack because of cops.”

Greg Almond, a Randolph County man who owned an engraving business, chicken houses, and several acres of land, before law enforcement raided his home and seized tens of thousands of dollars in property, discusses his family’s plight.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!