On Dec. 4, 2019, the Governor’s Study Group on Criminal Justice Reform convened at the Alabama Statehouse to hear proposals from the public on how to address Alabama’s prison crisis. Appleseed Research Director Leah Nelson was among the 20 presenters, including families of the incarcerated, formerly incarcerated, advocates, academics, lawyers, direct service providers, and faith leaders who shared proposals. Below are Leah’s comments, based on Appleseed’s extensive research around prison diversion programs.

Montgomery, Alabama — My name is Leah Nelson. I’m research director at Alabama Appleseed. I have spent 2 years surveying and interviewing hundreds of people in drug courts and diversion programs.

What I learned is that these programs are too expensive for people who lack wealth to participate in them without making outrageous sacrifices. And they are not designed to accommodate the everyday realities of folks who have jobs, children, or other obligations they must attend to.

Appleseed’s Leah Nelson shares her research on Alabama’s two-tiered justice system with the study group.

How many people in this room could drop everything several times a week to drive to another county to leave a urine sample? How many could get most of a day off once every couple of weeks to spend hours in a courtroom waiting for our chance to speak with a judge? Now imagine doing that if you were a single mom, if you worked at a job that paid by the hour and had an unpredictable schedule, or if you didn’t have a car.

I’d like to tell you a little about two people who cannot be here today.

The first person is a man named Ryan, who is in drug court in Shelby County right this minute and who will go to work after he’s through.

Ryan exemplifies the shortcomings of the system as it currently exists. In 2017, he was convicted of unauthorized possession of a controlled substance and put on probation in Chilton County. In early 2019, he reoffended in Shelby County and was accepted into Shelby’s drug court, widely acknowledged to be one of the toughest in the state.

Ryan excelled in rehab and got his life back together, but he didn’t understand he was supposed to still be checking in with his probation officer in Chilton. He thought his supervision had been consolidated in Shelby. When he learned there was a warrant out for his arrest, he turned himself in. He sat in jail for 3 months while much of the work he had done to rebuild his life disintegrated. He’s out now, but he’s struggling. He earns $400 a week to support himself and his young son. Between drug tests, supervision fees, drug court fees, and fines, he pays about $700 a month. That’s almost half of his income.

The second person I’d like to tell you about is a woman named Amber.

Amber was released from Tutwiler into Madison County Community Corrections this fall. She was so relieved be get home and get back to supporting and caring for her two teenaged sons. She received job training and multiple certifications while she was in Tutwiler. She couldn’t wait to get to work.

And she had to work, because Community Corrections requires her to pay $290/month for electronic monitoring plus another $20/week for drug tests. She had to bring them the first installment within 24 hours of her release or she’d be taken straight back to prison.

Amber has been offered multiple jobs, only to show up for the first day of work and be told they didn’t need her after all because of her felony. Right now, she brings home about $250 per week from unskilled labor she found through a staffing agency which takes part of her paycheck. About a third of her monthly income goes toward electronic monitoring and drug tests alone. That’s unsustainable.

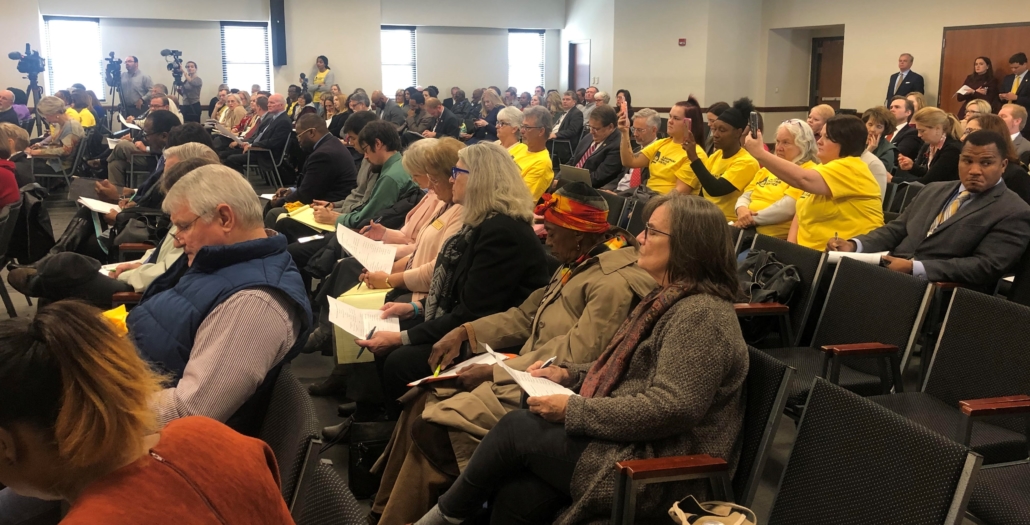

A packed room gathered to hear public proposals at the December 4 meeting of the Governor’s Study Group on Criminal Justice Reform.

She’s terrified of what going back to Tutwiler would mean for her family. When we spoke in late November, she wasn’t sure she’d still be home to spend Christmas with her boys.

Amber and Ryan are far from alone in struggling with the financial and operational obligations of diversion programs in Alabama. These programs have been described to the governor’s study group as unfunded, but that’s not accurate. The state doesn’t pay for them: instead, in most places, diversion programs are funded by the people who participate in them. And those payments are made at a terrible cost.

In 2018, Appleseed worked with partners to survey nearly 900 Alabamians about their experience with the courts. About 20% of the people we surveyed reported they were turned down for a diversion program like drug court because they could not afford it. About 15% had been kicked out of a diversion program because they were unable to keep up with payments.

In 2019, we followed up with a survey of a smaller group of people, all of whom had participated in some form of diversion program. Most of the people we surveyed were poor. 64% of them made less than $20K/year.

Most of them had been found indigent. Most of them had no idea how much the program would cost before they pled in. Yet they were still required to pay a median amount of $1500. Only one in 10 had ever had their payments reduced due to inability to pay.

Without that relief, two thirds gave up a basic necessity like food, rent, or car payments to keep up with their payments. More than a third took out a payday loan. And 30% admitted they had committed a crime to keep up with their payments.

Even so, 30% were forced to drop out because they couldn’t afford it or couldn’t keep up with the frequent drug tests and court appearances. The consequences were dire: One-fifth of people who were unable to complete their diversion program for structural or financial reasons found themselves incarcerated as a result. Our failure to make these programs workable for poor people is driving prison overcrowding.

Alabama can and must make diversion programs more accessible to poor people. To start with, judges should conduct individualized ability to pay determinations that take people’s financial realities into account.

Second, programs should be portable and easy to consolidate. As a rule, no one should be on more than one form of diversion or paying for supervision by multiple jurisdictions or entities. And folks should be able to serve their sentences where they live, not where they offended.

Finally, all diversion programs should track individuals’ progress and remain vigilant about how they can do better. If these programs are to serve their purpose of giving Alabamians who have made mistakes a second chance and keeping families and communities healthy and strong, they must account for the everyday realities of the people who participate in them.

There is a lot of promise in diversion, but these programs are not accessible to people who lack wealth. If we don’t take steps to correct this, Alabama will continue to have one form of justice for the rich and a very different one for the poor.

In January, 2019, Appleseed will release its full report on the two-tiered justice system created by prison diversion programs funded on the backs of participants.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!