State leaders promised to find an Alabama Solution to the “deeply humiliating” federal findings. But 698 incarcerated people have since died in state prisons, a new $1 billion prison will not open until 2026, and the federal trial is scheduled for next year.

By Eddie Burkhalter and Carla Crowder

This week marks the fourth anniversary of the U.S. Department of Justice report detailing such horrific and widespread violence, death, and sexual abuse inside Alabama’s prisons for men that state officials were forced into account for “severe, systemic,” constitutional violations meticulously documented in the 56-page report signed by all three Alabama U.S. Attorneys.

“This problem has been kicked down the road for the last time,” Gov. Kay Ivey said in a statement, six weeks after the report’s release. “Over the coming months, my Administration will be working closely with DOJ to ensure that our mutual concerns are addressed and that we remain steadfast in our commitment to public safety, making certain that this Alabama problem has an Alabama solution.”

Those concerns were not addressed. The DOJ issued a second report in July 2020 detailing widespread use of excessive force, including deadly force, by corrections officers against incarcerated people. And in December 2020, the federal government sued the state and the Department of Corrections in a case that is scheduled for trial in less than 18 months. At that time, DOJ lawyers will attempt to prove that the state “fails to provide adequate protection from prisoner-on-prisoner violence and prisoner-on-prisoner sexual abuse, fails to provide safe and sanitary conditions, and subjects prisoners to excessive force at the hands of prison staff,” as alleged in the lawsuit.

Those of us closely following the state’s promised responses, the so-called “Alabama solution” to the federal intervention, had reason to believe that there would have been progress by now against the constant violence, overcrowding, understaffing, corruption, and mismanagement documented four years ago by the Republican-led Justice Department..

Instead, all of the factors contributing to the “enormous breadth of ADOC’s Eighth Amendment violations” in the words of the DOJ, have gone in the opposite direction; they’ve gotten worse. Except for one – the population of individuals crowded into ADOC’s major facilities has declined by 511 since April 2019. But during this time frame, 698 incarcerated people have died in these prisons, according to ADOC’s monthly statistical reports. Thus, much of that decline can be attributed to the matter at the heart of the litigation, that “Alabama is incarcerating prisoners under conditions that pose a substantial risk of serious harm and death.”

Given that the clock is ticking on a trial that will have major ramifications for public safety and the justice system statewide, it’s important for Alabamians to understand how we got here, what has transpired in response, and how other states have fared in similar situations.

“Minimal Remedial Measures”

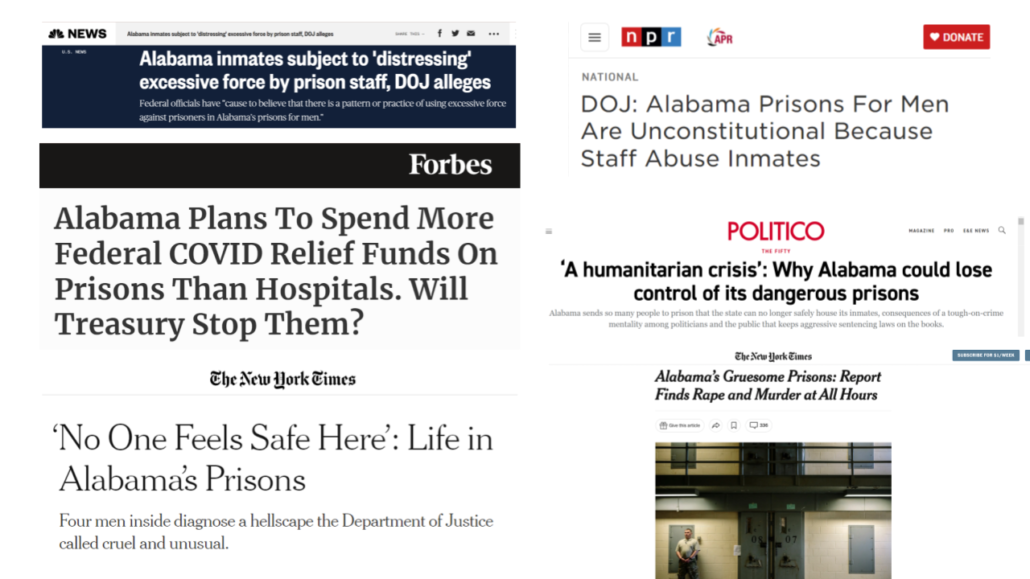

News headlines highlighting Alabama’s prison crisis

Alabama’s prison crisis was nothing new, but the federal government’s report – technically a Notice required by the Civil Rights of Incarcerated Persons Act (CRIPA), that provides statutory authority for the federal government to investigate and intervene in a state’s systemic failure to protect the incarcerated – brought the crisis to the nation’s attention.

Shameful neglect and abuse of thousands of Alabamians that had been hidden for years suddenly tumbled onto the front pages of publications ranging from the Montgomery Advertiser to the New York Times. Fox News quoted then-Sen. Cam Ward describing the findings as “deeply humiliating” for Alabama. “It’s disgusting. I mean, it is.”

If ADOC leadership were confused about how to begin to ameliorate the myriad of problems, all they had to do was to keep reading.

The 2019 report listed “minimal remedial measures” ADOC should take to begin making prisons safer and avoid a lawsuit. Among them:

- contact the director of the National Institute of Corrections to arrange a joint conversation between the department, NIC and the DOJ to discuss the areas in Alabama prisons that needed immediate attention.

- develop a centralized system to contain autopsy reports of all incarcerated people who die in ADOC custody.

- draft a policy requiring the screening of every person who enters prisons (staff, volunteers, visitors, etc…) and to implement that policy within one month.

- reclassify every incarcerated person for sexual safety issues, and ensure that potential predators are separated from potential victims.

- immediately begin shakedowns to stem the flow of contraband, such that 15 percent of all housing areas are searched every day, with congregate areas searched every week.

An ADOC spokesperson in a response to Appleseed on Monday said the department was and is in contact with the director of the National Institute of Corrections to receive advice and training on correctional-related issues, including a recent training on staffing analysis. ADOC’s response did not address the question about the DOJ’s recommendation to develop a centralized system to contain autopsy reports of all incarcerated people who die in ADOC custody.

ADOC also claimed in its response that some of the policies suggested by the DOJ were already in place and suggested that the federal lawsuit was premature. “Rather than continuing to collaborate with the ADOC to find workable solutions to these issues, DOJ surprised the state by abruptly filing suit in December 2019,” the ADOC stated. The lawsuit was filed in December 2020, twenty months after the Notice and following 52 deaths from homicide, suicide or drug overdoses in 2019 and 2020.

Subsequent DOJ filings, including the May 2021 amended complaint in the ongoing litigation, makes clear that ADOC has fallen short in addressing the primary contributor to the unconstitutional violence: contraband. (“ADOC told us that ADOC staff are bringing illegal contraband into Alabama’s prisons,” the 2019 report noted.)

According to the DOJ, illicit cellphones and drugs that pour into the prisons through cell phone usage are a major contributor to the widespread violence, as “the inability to pay drug debts leads to beatings, kidnappings, stabbings, sexual abuse, and homicides.”

The complaint goes on to note: “Although ADOC has not allowed visitors into Alabama’s Prisons for Men since March 2020 pursuant to COVID-19 restrictions, prisoners continue to have easy access to drugs and other illegal contraband,” suggesting visitors are not the source.

While ADOC has made arrests of officers charged with bringing in contraband, the flow of drugs, weapons and other contraband continues. Incarcerated people tell Appleseed that ADOC’s Correctional Emergency Response Teams often raid a prison dorm prior to a visit to the dorm by DOJ’s attorneys, clearing the area of contraband, only for it all to return shortly afterward.

ADOC continues to insist that incarcerated people are single-handedly responsible for the delivery of contraband: “The ADOC continues to employ a myriad of strategies to find and eliminate contraband in its facilities. As the ADOC explores and develops new strategies, inmates continue to find new ways to introduce contraband. Thus, ADOC’s efforts to find and prevent contraband are always evolving, and the department continues to look for new and innovative methods of eliminating the existence and introduction of contraband into its facilities,” the response reads.

None of the numbers are moving in the right direction

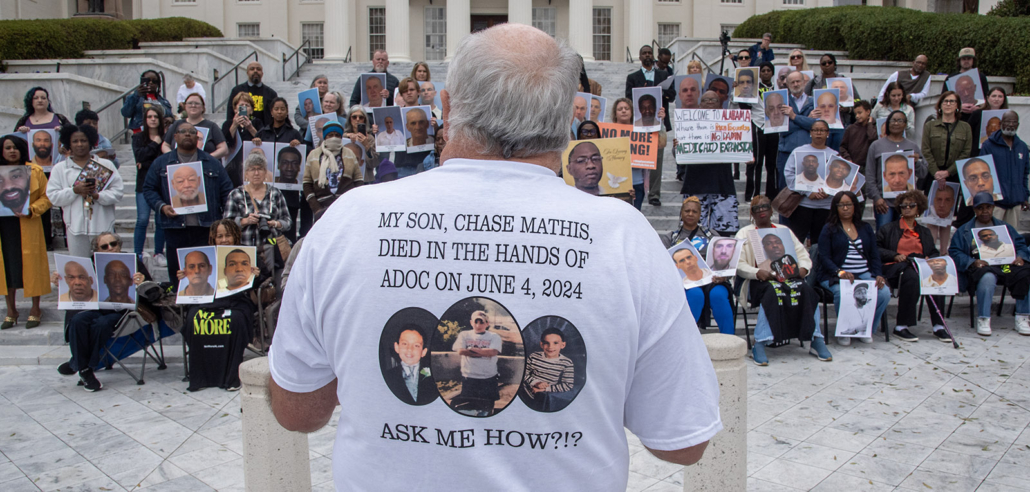

A vigil in remembrance of the nearly 300 people who have died in Alabama’s prisons this past year was held on March 7, 2023 at the State Capitol. Photo by Lee Hedgepeth.

Year after year conditions have only worsened, and promises from state leaders then to fix the crisis have yet to materialize.

The DOJ report noted that an “egregious level of understaffing” results in increased violence and death, with prisons employing 1,072 of the 3,336 authorized officers. Four years later, ADOC Commissioner John Hamm stood in front of legislative budget leaders, basically threw up his hands at the persistent lack of security staff and asked with a straight face, “any suggestions you have we’re all ears.”

U.S. District Judge Myron Thompson in a separate case about mental health care in prisons in 2017 ordered the state to hire an additional 2,000 correctional officers, but in February, 2023, the judge warned the state that staffing remains critically low. “We had horrendous understaffing in this department and something has to be done,” Thompson said.

Again, the numbers are moving in the wrong direction.

ADOC’s quarterly report published in January states that for the fiscal year ending on Sept. 30, 2022, ADOC recorded a net decrease of 415 security employees. The latest quarterly report shows another net loss of 52 security staff as of Dec. 31, 2022.

ADOC has added new types of security staff to try and boost numbers – cubicle operators who can only operate doors, and basic correctional officers who have a shorter training period than other officers. The agency raised salaries so that officers at maximum security facilities start at $55,855, a salary it would take 17 years as a public school teacher to earn. It’s too soon to tell if that salary will help recruitment. Nothing else has.

These deficits are not abstract for thousands of Alabamians living in prisons and for desperate family members who just want their loved ones to finish their sentences alive.

In images shared on social media by incarcerated people, correctional officers in several Alabama prisons can be seen sleeping inside their cubicles. Incarcerated people tell Appleseed that they’re often left to fend for themselves if attacked. In instances when a person is critically wounded, officers have been slow to respond, sometimes resulting in death while other incarcerated men clamor to get officers’ attention to render aid.

“Inmates have knives and axes and drugs including fentanyl; they are available in copious amounts in these prisons,” wrote the mother of a man serving 15 years at Limestone prison. “He was attacked while on the phone 3 days ago and said nothing to anyone about it because that’s what causes you to be stabbed. He was attacked this morning going into the bathroom and now has a broken rib and received 7 stitches in his mouth and sent back to his dorm.”

If understaffing is one ingredient in the deadly mixture that makes up state prisons, overpopulation is the other.

The month that DOJ’s report was published in 2019, Alabama prisons were at 168 percent capacity, according to ADOC’s statistical report. Alabama prisons remained at 168 percent capacity in January, according to the latest report.

To add to the deadly mixture, paroles in Alabama have plummeted since 2017.

During the 2022 fiscal year the three-member Pardons and Paroles Board denied 90 percent of applicants for paroles, according to board statistics, down from 46 percent denied during fiscal year 2017, and Black applicants are being paroled less than half as often as white applicants.

During the 2022 fiscal year the three-member Pardons and Paroles Board denied 90 percent of applicants for paroles, according to board statistics, down from 46 percent denied during fiscal year 2017, and Black applicants are being paroled less than half as often as white applicants.

What happens when you have understaffed, overpopulated prisons? According to the DOJ report, “inadequate supervision that results in a substantial risk of serious harm.” The report highlighted five stabbing deaths in prisons that year in which those men had previously been stabbed and survived. “ADOC, with the knowledge that previously stabbed prisoners were at risk for further violence, took no meaningful efforts to protect these prisoners from serious harm—harm that was eventually deadly,” the report reads.

The meticulous documentation of death after death after death seemed shocking in 2019. But shock gave way to resignation and this grim status quo is just that, just the way prisons are, for most of Alabama’s elected leadership. In a recent meeting to discuss prison conditions and possible solutions, a freshman representative dismissed our concerns, saying that prisons aren’t supposed to be “the Taj Majal.”

Against the persistent backdrop, prison deaths have surged, reaching a record high 270 last year, more than double the 130 deaths in 2019 when the report was released and officials vowed to take the bloodshed seriously. At that time the homicide rate in Alabama’s prisons was eight times the national rate. It has gotten worse.

At least 95 of the 270 deaths in 2022 were preventable deaths: homicides, suicides, and confirmed or suspected drug-related deaths, according to investigative reporter Beth Shelburne. This is the highest number of preventable deaths since she began tracking them in 2018.

So far this year someone has died in Alabama prisons every other day. Our research has confirmed 36 prison deaths. Among those, 27 were suspected to be overdoses, one suicide and four suspected homicides.

Study group formed, but results lacking

The Governor’s Study Group on Criminal Justice Policy. Photo courtesy of the Associated Press.

We are not suggesting state leadership has not responded to the allegations in the four-year-old report, but the meager responses have produced few results to assuage the breathtaking brokenness of Alabama’s largest law enforcement agency as documented in 2019. And the 2023 legislative session so far has seen efforts to fast-track bills that will increase prison sentences and intensify the ADOC chaos.

Initially, the Governor’s Office promised a multi-faceted, data-driven solution. By executive order three months after the DOJ report was released, Ivey formed the nine-member Governor’s Study Group on Criminal Justice Policy and tasked the members with analyzing data and best practices, and seeking solutions to the prison crisis.

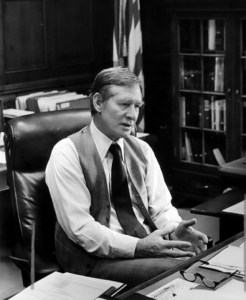

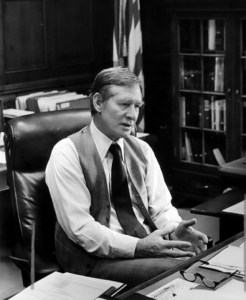

Former Alabama Supreme Court Justice Champ Lyons and chairman of the Governor’s Study Group on Criminal Justice Policy

The task force met for seven months and in a 10-page letter to Ivey suggested modest sentencing reforms, a focus on educational and rehabilitative programs aimed at reducing recidivism and an increase in the number of people released early and placed on mandatory supervision.

The study group noted that a 2015 law that allowed for early release and mandatory supervision for some incarcerated people only applied to those sentenced after 2015, and suggested it be expanded to those sentenced prior to the law being enacted. Under the law those sentenced to up to five years could be released as early as five months before the end of their sentence. Those serving up to 10 years could be released as much as a year early.

A bill to impact those sentenced before 2015 passed decisively with bipartisan support in 2021. Its supporters saw it as a way to reduce recidivism and ease prison overcrowding, noting studies that found that monitoring those released does just that.

Systematic problems with underfunded, chaotic victim notification systems slowed those early releases, Appleseed discovered, but once releases began, pushback was swift and now there is legislation to undo this slim bit of reform.

“When this bill passed in 2021 originally, it was something that I was very much opposed to, and had concerns about the passage of,” Sen. Chris Elliott, R-Fairhope, told Alabama Reflector. Elliott filed a bill on Jan. 31 that would delay those early releases until 2030.

Ivey’s study group also recommended enhanced early release incentives.

Sen. April Weaver (R-Brierfield) introduced the Good Time Bill in the 2023 legislative session

“As with sentencing reform, public safety requires great caution in determining who might be eligible for such incentives,” study group chairman and former Alabama Supreme Court Justice Champ Lyons wrote to Ivey. “Nevertheless, we support the award of early release incentives for those inmates who complete certain courses and maintain good behavior while incarcerated.”

The Alabama Legislature approved of that recommendation, and Ivey in May 2021 signed into law a bill that reduces prison sentences by up to one year for incarcerated people who complete academic and vocational programs while in prison.

But it didn’t take long for the Legislature to begin working to reverse that gain, and 10 months after Ivey signed that the Alabama Senate approved a bill sponsored by Sen. April Weaver, R-Brierfield, that would reduce the amount of “good time” incarcerated people can earn.

Weaver has cited the June 2022 shooting death of Bibb County Deputy Brad Johnson as the impetus. Austin Patrick Hall, who has been charged in the death, was allowed early release on good time despite numerous infractions, both in and out of prison, including an escape, for which Hall was not charged for three years – until after Johnson’s death.

Had ADOC followed existing law and forfeited Hall’s good time after his escape from the Camden Work Release Center in 2019, or if Hall had been timely prosecuted for the escape, Hall would not have been out of prison when Johnson was shot, the Alabama Political Reporter noted in August 2022.

Rep. Chris England (D-Tuscaloosa) has repeatedly sponsored bills aimed at reducing the prison population and holding ADOC accountable

In reality, a dysfunctional system unable to follow laws already in place contributed to Johnson’s death. Lengthening sentences in prisons unable to provide rehabilitative services or even keep prisoners alive is unlikely to produce the public safety results Alabama deserves. It’s important to recognize that multiple instances in which lawmakers have toughened sentences were in response to individuals who have served time in these hellish settings, been released with no rehabilitation and then gone on to harm Alabamians.

Not all lawmakers have been complacent. Rep. Chris England (D-Tuscaloosa) has repeatedly sponsored bills aimed at reducing the prison population and holding ADOC accountable. England’s bill requiring increased reporting by ADOC passed in 2022. The agency now posts quarterly reports that document drugs and weapons confiscated at the prisons. The reports routinely list free world weapons and even firearm confiscations. But no one in state leadership has expressed concerns about this new data.

Alabama’s long history of abusing the incarcerated until federal officials make us stop

When it comes to Alabama’s prison crisis, there’s nothing new under the sun.

That’s how Austin Sarat, the William Nelson Cromwell Professor of Jurisprudence and Political Science at Amherst College in Massachusetts, described the state’s prison problems, and placed them into historical context during a conversation with Appleseed. Sarat has been a visiting professor at the University of Alabama School of Law, teaching a course on punishment.

Sarat discussed U.S. District Court Judge Frank Johnson’s 1976 opinion in the landmark Alabama case Pugh v. Locke, in which the plaintiff, an incarcerated man named Jerry Pugh, sued ADOC for failing to protect him and others from violence in violation of the Fourth and Eighteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

U.S. District Court Judge Frank Johnson’s 1976 opinion in the landmark Alabama case Pugh v. Locke. Photo by Birmingham News.

Johnson agreed, and appointed a special master to ensure ADOC followed his orders to resolve the dangerously unconstitutional conditions nearly 50 years ago. ADOC remained under federal supervision for 13 years. The Court enjoined ADOC from accepting any new prisoners, except escapees, into four prisons until the population was reduced. In July 1988 ADOC was forced to release 222 incarcerated people early. State prisons had many of the same problems then as today; they were overcrowded and violent, the buildings were dilapidated and unsanitary. “Reading the DOJ report and findings, if you close your eyes, it could have been Frank Johnson writing them,” Sarat said.

Sarat described Johnson’s remedial decree as “extraordinarily detailed and quite controversial.”

“At the time that he made the decision, he was among the first judges to say that prisoners retain all rights, except those necessarily lost as an incident of confinement,” Sarat said.

Lost in the emphasis on prison construction as a remedy to the current crisis is the fact that Alabama embarked on a prison building spree in the 1980s to make things right. It was not a long-term solution.

A warning from California and a lesson from Texas

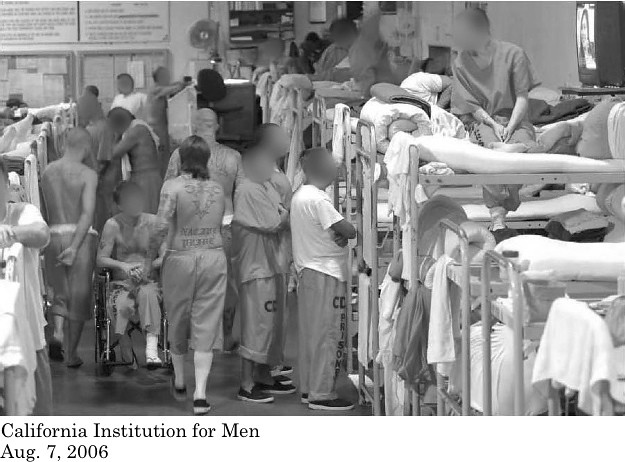

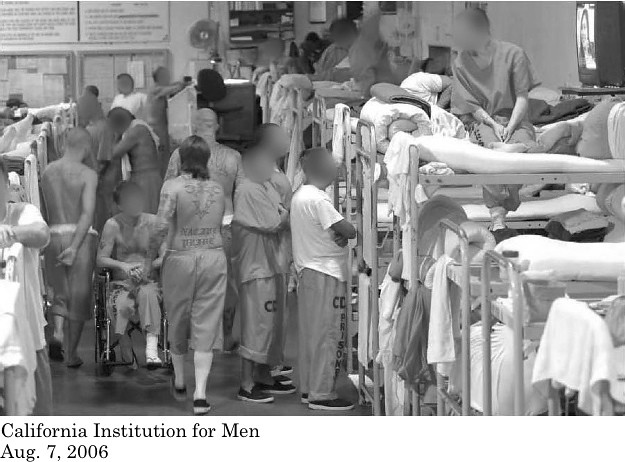

California Institution for Men from Brown vs. Plata

What could Alabamians expect to come out of the federal government’s lawsuit over Alabama’s broken prisons? One might look at a similar case in California that resulted in a court order to reduce the state’s prison population by more than 30,000 people within two years.

“The situation had gotten so bad, reading the Plata decision, I realized that we were really heading down the exact same road,” said then-Sen. Cam Ward, as chair of the Legislature’s Prison Oversight Committee eight years ago.

The U.S. Supreme Court in the 2011 Brown v. Plata case ordered California to remedy unconstitutional conditions that deprived incarcerated people of adequate medical and mental health care. For starters, the State had to find a way to reduce its prisons to 137% of designed capacity from about 200%. One tactic, called “realignment” required county systems to house all non-violent and non-sex offenders upon conviction to free up prison space for everyone else. Implementation was not easy, however, given that most county jails lacked unused space as well as sufficient treatment and programming to provide rehabilitation.

It’s important for Alabama officials to recognize the Plata Court’s emphasis on violence and death. The Court noted that in 2006 “a preventable or possibly preventable death occurred” somewhere in California’s prison system “once every five to six days.”

Alabama is worse. Our prisons have thousands fewer people than California’s, but more deaths. In Alabama prisons so far this year, someone has died every other day. Of the 36 deaths in Alabama prisons Appleseed has confirmed so far this year, 32 were preventable.

If Alabama’s conservative “tough on crime” lawmakers might wince at the notion of looking at California for answers to Alabama’s problems, perhaps they should look at Texas.

Texas was on track to need 17,000 new prison beds by 2012, at a cost of approximately $2 billion, but instead, lawmakers appropriated $241 million for drug treatment programs in and outside of prisons, and created specialty courts to handle those struggling with drugs, and veterans in need of special care.

“According to Texas Department of Public Safety statistics, from 2007 to 2008 Texas saw a 5 percent decline in murders, a 4.3 percent decline in robberies, and a 6.8 percent drop in rapes,” according to the Daily Beast. “ In those same years, Right on Crime, a conservative think tank devoted to criminal justice reform, reports the number of parolees convicted of a new crime fell 7.6 percent; the number of incarcerations dropped 4.5 percent.”

Texas lawmakers in 2011 closed the state’s second-oldest prison, and within another two years shuttered two more prisons.

“You want to talk about real conservative governance?” then-Texas Gov. Rick Perry asked the audience at the 2014 Conservative Political Action Conference. “Shut prisons down. Save that money.”

Alabama’s Billion Dollar Solution

Thus far, the Alabama Solution does not involve saving money.

The DOJ in the 2019 report wrote that while new buildings may solve some of the problems it identified “new facilities alone will not resolve the contributing factors to the overall unconstitutional conditions.”

Even so, dating back to Ivey’s predecessor, Gov. Robert Bentley, the plan for many years has been to build new prisons, with the promise that doing so will solve the crisis.

Ivey’s previous plan, which called for new prisons to be built by the private prison company CoreCivic and leased to the state at a cost of $3.6 billion, fell through when CoreCivic was unable to secure financing for the deal, following much pressure against financial firms from investing in prisons.

Alabama lawmakers in 2022 approved $1.3 billion to build two 4,000-bed prisons for men, agreeing to direct $400 million in federal COVID aid toward the projects. That budget includes a $785 million bond issue and $135 million from the state’s General Fund. The state in April 2022 signed a $623 million contract with Caddell Construction to build a 4,000-bed prison for men in Elmore County.

Last month, the cost of one prison jumped to $1 billion and the expected completion date was extended several months. At this rate, it will not be open until about 2 years after the 2024 trial. A second prison, promised for Escambia County, is without a contractor and seemingly without most of the funding needed to build it, unless state leaders have a surprise funding stream. Gov. Ivey has requested $100 million from the Education Trust Fund budget to go into prison construction, but that still would not come close to bridging the funding gap created by the Billion Dollar Prison.

It’s unclear how the state will pay for the second planned new 4,000-bed prison in Escambia County. The new construction will not add space, but will only replace dilapidated prisons.

“Alabama is not the only state, but it turns out that it seems that prison construction is one place where budget constraints, at the end of the day, often don’t matter,” Sarat told Appleseed. “They matter in public education. They matter in health care. They matter in infrastructure, but it doesn’t seem to matter all that much when it comes to how much we’re going to spend on the prison system.”

“This is abnormal and so wrong.” Views from the inside

Family members at the Vigil for Victim’s on March 7, 2023. Photo by Lee Hedgepeth

Beyond the back-and-forth between state leaders and the federal government attempting to hold them accountable are the voices of people barely surviving in the prisons they were supposedly sent for rehabilitation.

The sister of a man serving at Bullock prison described to Appleseed two separate attacks that nearly cost her brother his life. “My brother was assaulted on March 6th and 21st 2021 at Bullock Correctional Facility. He almost lost his life on the 21st; he had to be airlifted, placed on life support and was left with a collapsed lung, [and] they returned him from the hospital within 3 DAYS!!!! They put him back in population, with stitches, staples, a tube and he had to sleep on the floor!!!!!! He was stabbed over 30 times,” the sister wrote.

A man who served several years at Fountain Correctional Facility told Appleseed that when he first entered the prison he had no idea what he was in for. “Over the 2 years I was there I saw more stabbings than I could count and was beaten several times myself,” the man wrote. “I woke up one night tied to my bunk and was beaten and sexually assaulted for what seemed an eternity. I continued to be sexually assaulted multiple times and never reported it for fear of being killed if I did.”

“I was forced to do things that I never dreamed of doing in order to survive,” he said in the letter. “I tried reporting one incident when I was almost stabbed by someone who was trying to rape me and wasn’t taken seriously by officers, even humiliated and made fun of.”

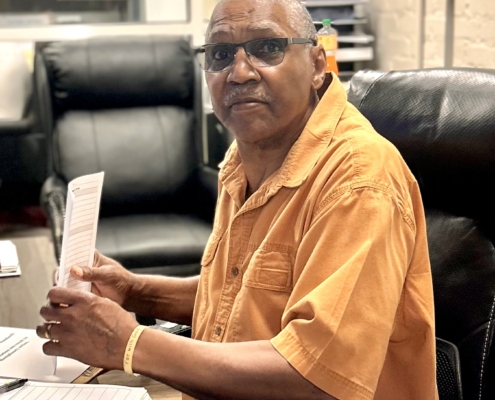

An elderly man serving a sentence of life without parole at Donaldson Correctional Facility wrote to Appleseed about his concerns over understaffing, poor living conditions and the rash of overdoses.

“At night time [there is] only one officer to watch 650 prisoners,” he wrote. “We have prisoners here who are ‘homeless.’ Prisoners who are afraid to to go into an assigned cell b/c of being raped, set up to be robbed, beat up, and etc. These prisoners sleep in the open day room, some sleep under the stairs, some sleep in the old–not used–showers.”

Donaldson prison’s infirmary sees two to three overdoses daily. “We have had as much as 5 in one day. The Infirmary does not keep a count on overdoses…90% of the contraband coming into prison is coming in by officers; and these officers are being aided with the help of other officers.”

Four years ago, the DOJ began its report, with a description of a scene from Bibb County Correctional Facility: “At the back of the dormitory and not visible from the front door, two prisoners started stabbing their intended victim. The victim screamed for help. Another prisoner tried to intervene and he, too, was stabbed. The initial victim dragged himself to the front doors of the dormitory. Prisoners banged on the locked doors to get the attention of security staff. …The prisoner eventually bled to death. One resident told us he could still hear the victim’s screams in his sleep.”

The State of Alabama still houses tens of thousands of people in these conditions. Four years after a blistering warning from the U.S. Department of Justice, nothing has changed.

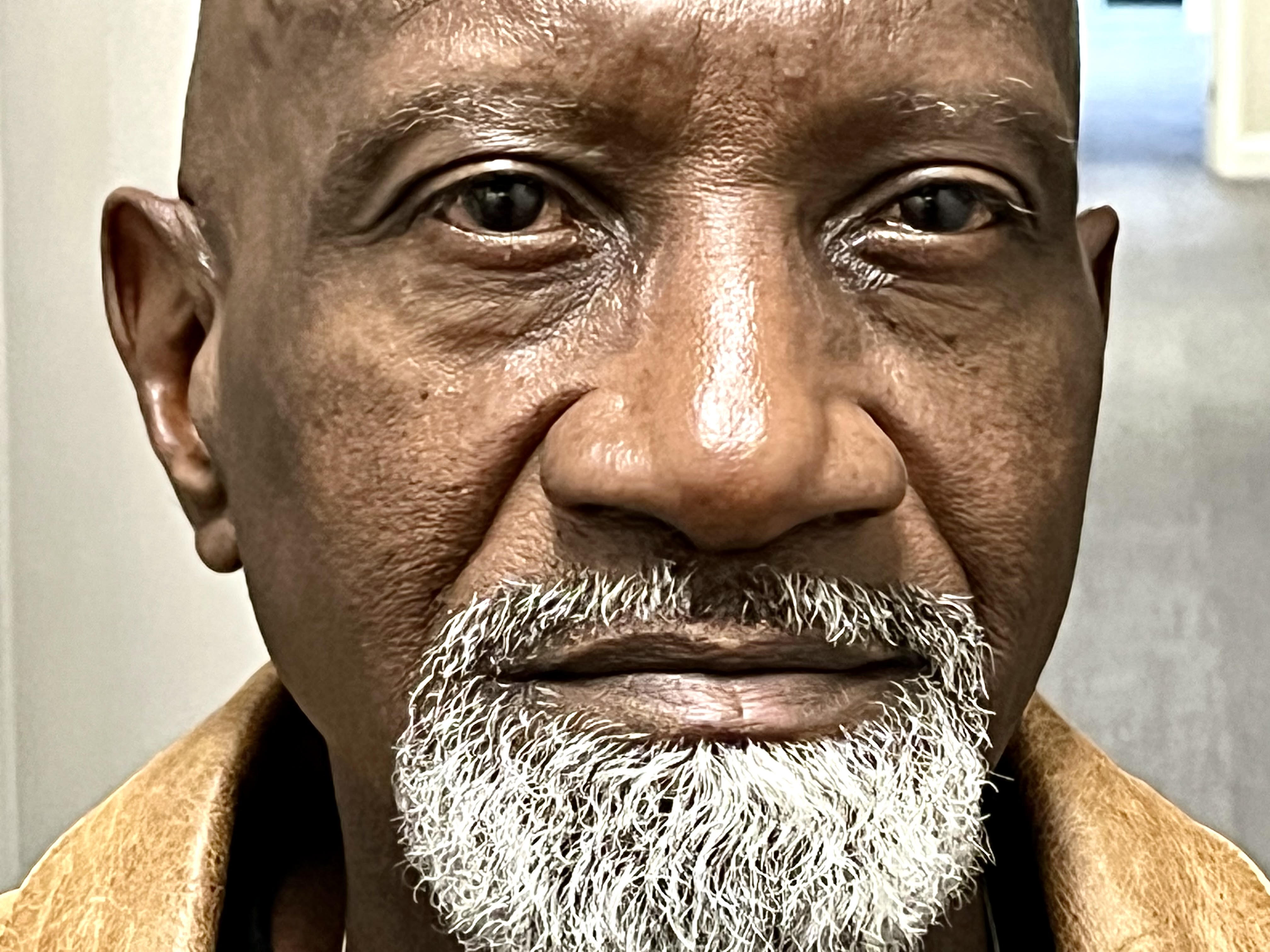

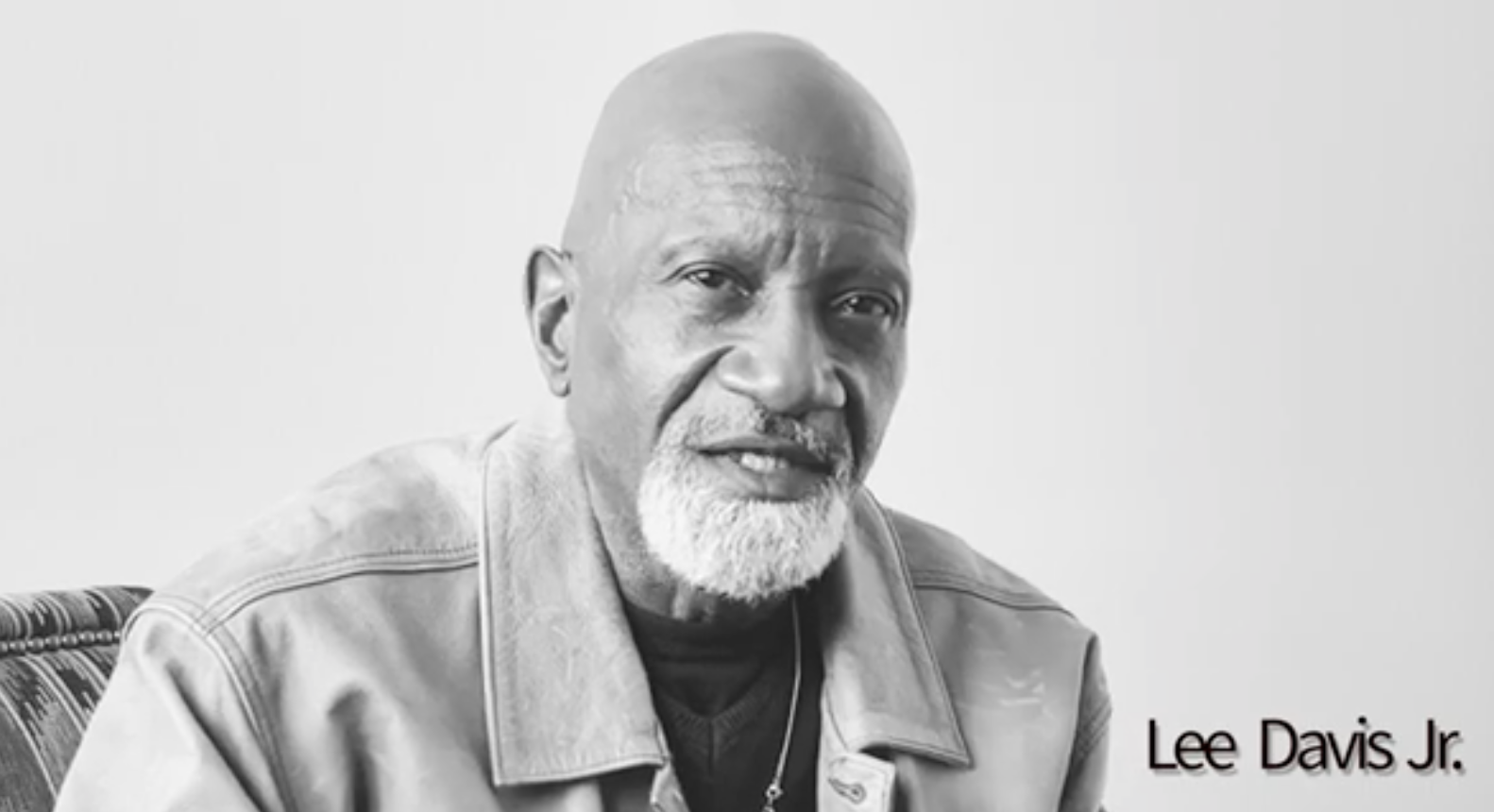

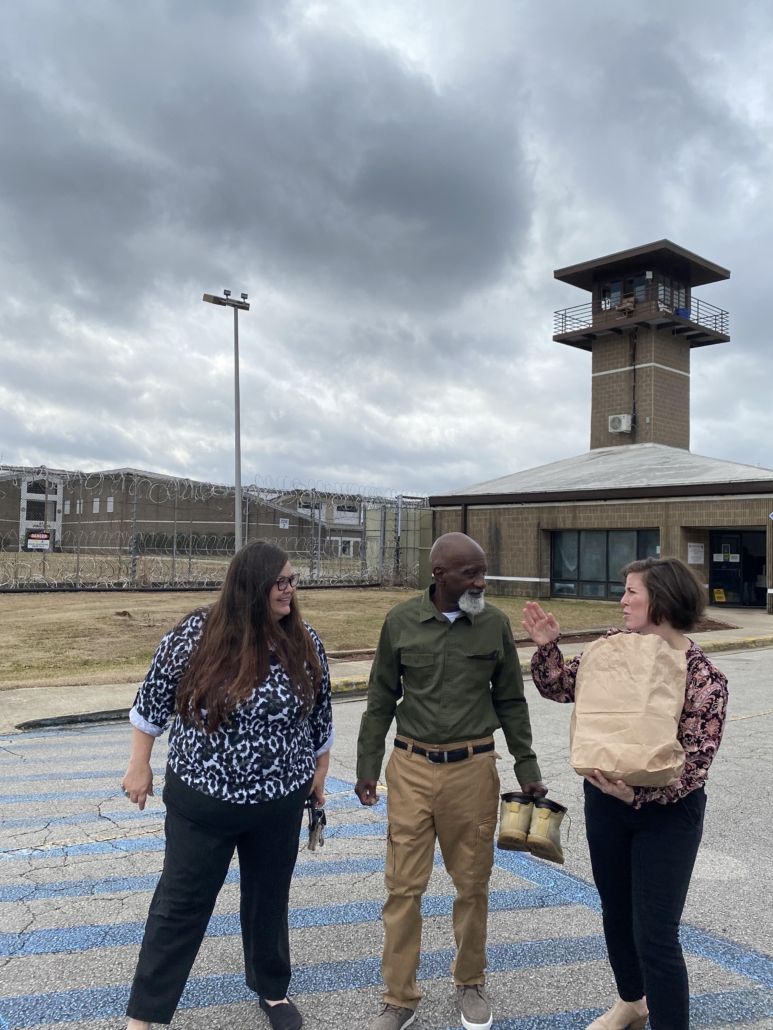

In July, Antonio Wallace wrote to Appleseed from Bibb. Wallace had survived in Alabama’s prisons since age 17. He had served 35 years for his role in a murder at age 16 when he was homeless and using drugs. Wallace was hoping to finally be granted parole. “I’m ready to come back [into] society and live the life of which I know what I suppose to do, be the father to my daughter and a grand dad to my grand baby girls,” Wallace wrote. “So I ask again: please don’t let me die in here.”

Just three months after sending this letter, Wallace was found unresponsive and pronounced dead, the result of a suspected overdose, according to sources inside Bibb prison. He was 51 years old.

“Yes I was a juvenile when I got off into this mess and from there my life hasn’t been much of anything and it’s sad when I look back at my situation and see nothing from there,” Wallace wrote. “I know I have good in me. I know I can function, if and when [given] a chance back into society. …I came in as a juvenile and I had to grow up in a place such as this which is abnormal and so wrong.”

Appleseed Legal Assistant Libby Rau contributed to this report.

During the 2022 fiscal year the three-member Pardons and Paroles Board denied 90 percent of applicants for paroles, according to board statistics, down from 46 percent denied during fiscal year 2017, and Black applicants are being paroled less than half as often as white applicants.

During the 2022 fiscal year the three-member Pardons and Paroles Board denied 90 percent of applicants for paroles, according to board statistics, down from 46 percent denied during fiscal year 2017, and Black applicants are being paroled less than half as often as white applicants.