By Eddie Burkhalter and Leah Nelson

Public outcry over the arrest of an 82-year-old Valley woman for $77 in unpaid garbage bills was swift, but records show the city has for decades arrested people over unpaid trash bills.

Martha Menefield’s arrest three days after Thanksgiving, made international headlines. The charge against her was dropped after Menefield, on Dec. 5, paid the $77 and an additional $35 in court costs, records show. But an investigation by Alabama Appleseed and other outlets indicates that Menefield was but one of many victims of Valley’s trash police.

This pattern of deploying police officers as bill collectors, particularly where the impacted residents are elderly, impoverished or both, does nothing to improve public safety and tarnishes the reputations of the small towns involved.

Under a 2012 Valley municipal ordinance, nonpayment of garbage fees is a misdemeanor punishable by fine. Appleseed reviewed 26 arrests of Valley residents charged with failing to pay solid waste fees, 11 of which took place this year. Of 26 cases reviewed, 11 people had been arrested more than once over unpaid trash bills.

Among those who were arrested on trash warrants by Valley police was 77-year-old Dee Kent, who was pulled over and arrested in November of 2021 while on her way to an appointment with her oncologist, CBS 42 first reported.

Kent, now 79, told the news station she’d received no warning from the city prior to her arrest for failure to pay $141 in trash bills. She described her arrest to Appleseed by phone Thursday as “embarrassing.”

“It was rough going to jail. Especially when everyone knows you. When you’ve grown up here,” Kent said.

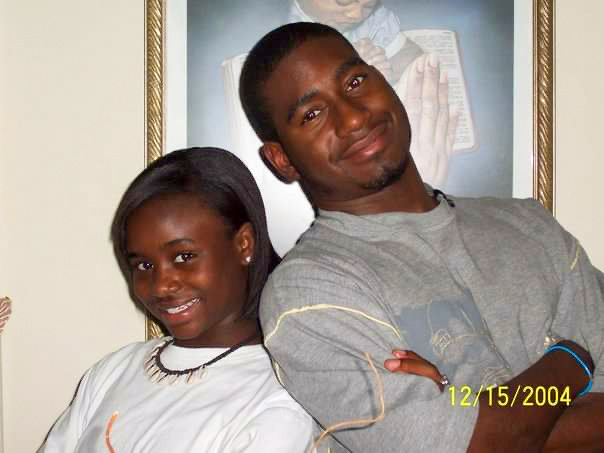

Nortasha Jackson, 49, was arrested Nov. 26 at her Valley home for $88 in unpaid trash bills, court records show. Her charge is listed as “Failure to Pay Solid Waste Fees” in those records.

Jackson said she was arrested by two officers, one white and one Black, and described the younger Black officer as “gung ho.”

“I came here to do my job. You’re going to be arrested,” the younger officer told her, Jackson said.

Once at the Valley Police Department, she was given 20 minutes to arrange her bail or else be taken to the county jail. Panicked, Jackson said she got help from her adult son who was able to transfer a payment to help secure the bond before she was to be moved.

Jackson’s three children are grown and all have moved on. She receives partial disability benefits and works full time as a cashier, but her health problems prevented her from working during the months of October and November, Jackson said, meaning she had to stretch what little income she had even further.

“It’s really hard,” she said. “My health is more important.”

How a law becomes an arrest

With a few exceptions, participation in Valley’s garbage service program is mandatory. Residents are required to pay $18.10 per month for the service, or $15.60 if they are 65 or older and apply for an exemption. People who rely exclusively on Social Security benefits for income can also apply for full exemption.

Penalties for nonpayment include late fees, suspension of services, and civil actions. And pursuant to an ordinance adopted in 2012, people who violate any element of the city’s solid waste code “shall be guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon conviction, shall be fined not less than $50.00 nor more than $200.00.” The ordinance spells out that those fines can be compounded, with each day of noncompliance constituting a separate offense.

Valley has clarified that Menefield was arrested for failure to appear, not strictly for failure to pay her trash bill. But in Valley – along with at least 47 other Alabama cities – failure to pay trash bills alone is technically enough to trigger criminal charges.

How does enforcement transpire? Every town operates differently, but to get a sense of how cities go about enforcing criminal codes where the offense in question is not something that would result in a call to 911 or a police stop, Alabama Appleseed spoke with two former city clerks who worked for small rural towns in Alabama.

The former clerks, who between them have decades of experience in municipal governance, explained that it is common for cities to contract with outside companies to collect their trash, as Valley does with a company called Amwaste. The cities pay the bill for that service, and city councils have discretion to pass those costs on to residents by passing a local ordinance. Fees collected pursuant to such ordinances have to be used for trash-related purposes and cannot be disbursed to the general fund.

Generally, the clerks said, cities have an entity – a water or utilities board in some, a solid waste department in others – that oversees garbage collection services and collects fees from residents. In order to keep track of payments, that entity maintains a list of delinquencies, which in a city with an ordinance permitting criminal consequences it could turn over to a magistrate on a periodic basis. Based on that list, the magistrate would issue warrants which police would be tasked with executing.

“I imagine they don’t even think about it, it’s just automatic. I think it probably stems from a policy set by the council or a directive from the mayor, but the magistrate is just doing what they do,” said Herman Lehman, former city clerk and treasurer for the city of Montevallo who now works as a consultant.

Lehman said that every single step of that process involves discretion. Like Valley, Montevallo contracts with an outside company to collect trash. The city pays the bill each month and collects fees from residents, who are required to participate in the service but can obtain exemptions if they can show they are unable to pay. As in Valley, Montevallo city code makes nonpayment of trash fees a misdemeanor.

Lehman said he is unaware of the city ever having enforced that provision of its code. Instead, when Montevallo found a resident was struggling to pay, it sought to connect them with assistance through local churches, community-based organizations, or a Shelby County fund that is available to people with certain types of financial difficulties. Montevallo also made sure that eligible individuals knew they could apply for exemptions from the mandatory fee. When people habitually failed to pay or act on their bills, Montevallo used civil and administrative measures to sanction them and attempt to recover the money.

“The idea that police were there to protect and serve, we sort of felt that serve was the operative word,” Lehman said of Montevallo’s reluctance to deploy police as debt collectors. “It just doesn’t make sense when you’re living in a community, particularly in a small community, to always play the bad guy, particularly in a situation where people may need help.”

Alabama law does not require custodial arrests for all misdemeanor charges. Among myriad unserved warrants for a wide variety of offenses dating back to 2003, Appleseed identified 22 for unpaid trash bills throughout Chambers County, along with one unserved warrant for the offense of “pants below waist.”

It is possible that the city of Valley issues summons initially, telling people who are delinquent on trash fees to come to court on a particular day for a hearing before a judge. What seems to have happened with Menefield is that she missed her initial court date. Typically, failure to appear at a court date prompts the issue of a second warrant, this time for failure to appear. That is the type of warrant that led to Menefield’s November arrest.

But even failure to appear warrants are subject to discretion, retired Birmingham Police Captain Jerry Wiley explained to Alabama Appleseed. Wiley said that police in Alabama are required to take people into custody for certain misdemeanor charges such as driving under the influence. But alternatives to arrest, including warnings and admonitions to resolve the problem that prompted the warrant, are available for many misdemeanors. In a small town like Valley, Wiley said, expectations about how police should proceed in cases like Menefield’s are set by the police chief, who answers to the mayor and/or city council. Though individual officers legally have the discretion not to arrest for certain offenses, Wiley said that in a small town, they would have little authority to defy such policies without risking their jobs.

But using police to punish nonpayment comes with a price for public safety. Research shows that when residents perceive police as debt collectors with badges, violent crimes are solved at a lower rate.

“If the only thing you’re interacting with your police department is for is arbitrary arrests and silly things like that, it becomes an adversarial relationship,” Wiley said. “If the police are out doing this, they’re not fighting the crime they should be fighting.”

The Costs of Debt

Making failure to pay trash fees a criminal offense doesn’t only make police officers debt collectors. It also results in many of those residents owing much more than their original fees.

Court records show that the average cost of unpaid garbage fees in those cases was $138.79. But as the cases progressed through the court, the average cost of all fees and additional court costs levied ballooned to an average of $402.

The racial breakdown of the arrests mirrored Valley’s racial demographics fairly closely: 42 percent of the people arrested in the 26 cases reviewed by Appleseed were Black, and the town’s population is about 38 percent Black.

These arrests could be stopped in a number of ways, but doing so would require action from Valley Mayor Leonard Riley and the seven-member Valley City Council, which could vote to change the language in the ordinance that makes nonpayment a misdemeanor. City officials could also simply stop the process that leads to the referral of those who are behind on payments for prosecution, and instead handle those debts as civil matters.

Several attempts to reach Valley city officials and its police chief this week were unsuccessful. The only public statement from city officials was from Valley Police Chief Mike Reynolds, who in a press release stated that while officers can use discretion in certain matters “the enforcement of an arrest warrant issued by the court and signed by a magistrate, is not one of them.”

“City of Valley Code Enforcement Officers issued Menefield a citation in August of 2022 for non-payment for trash services for the months of June, July, and August,” the statement reads. “Prior to issuing the citation, Code Enforcement tried to call Menefield several times and attempted to contact her in person at her residence. When contact could not be made, a door hanger was left at her residence. The hanger contained information on the reason for the visit and a name and contact phone number for her to call. The citation advised Menefield that she was to appear in court on September 7, 2022, in reference to this case. A warrant for Failure to Pay-Trash was issued when she did not appear in court.”

Jackson, the Valley woman arrested at home on Nov. 26, said the city needs to change how it handles unpaid garbage debt. She said that using police officers to collect such small amounts is “really stupid” and is not the sort of work taxpayers want from police departments.

“It needs to be done better. It stigmatizes people,” she said.