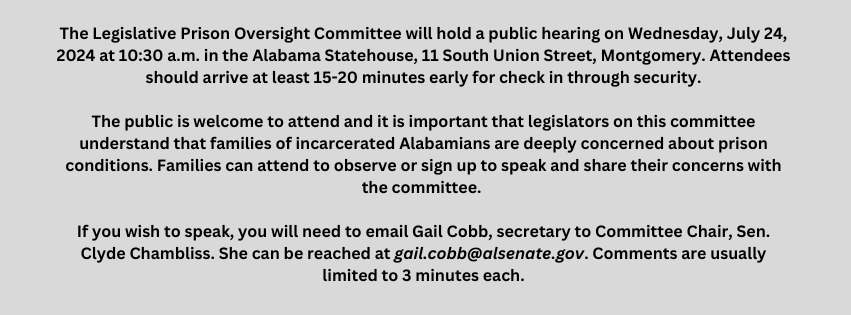

Wesley Abernathy was set to be released in December 2025. He had been sentenced to 30 months in ADOC. He died at Bullock Correctional Facility on Mother’s Day this May (photo courtesy of the family),

By Eddie Burkhalter, Appleseed Researcher

Like many Alabama families, Wesley Abernathy’s mother, wife, and sister paid thousands of dollars in extortion payments hoping the money would keep him alive during his short sentence in an Alabama prison. “We have gotten threats from other inmates in there. I was suckered into paying money,” his sister, Darby Martinez explained. “One time he was on the phone with me, and somebody got on there and said, ‘if you don’t send me this money, I’ll kill him tonight.’”

The family paid dearly. But Wesley died anyway.

“I had to tell my mom. It was horrific. I think that’s the worst pain that I’ve ever been through,” Mrs. Martinez told Appleseed. Wesley, 31, was her mother’s only son. He died at Bullock Correctional Facility on Mother’s Day this May.

Mrs. Martinez talked to her brother by phone the night before he died. They talked for eight minutes, until 10:58 p.m. “I’ll call you on Mother’s Day. Tell mom and everybody to answer,” Wesley told his sister. Instead, Mrs. Martinez got a call from a prison employee at 6:58 a.m.

“Let me switch you over to the chaplain,” the man told her. “I knew instantly something was wrong. He couldn’t get the chaplain to answer so he told me ‘I’m very sorry but Wesley passed away.’ I don’t really remember much from that moment. I know they said that I just fell to the ground and was screaming,” Mrs. Martinez said.

Wesley Abernathy with his sister, Selena Colon, his mother, Aleshia Gonzalez, and his sister, Darby Martinez (photo courtesy of the family),

Wesley was set to be released in December 2025. He had been sentenced to 30 months in ADOC, followed by probation, after pleading guilty to manslaughter.

From January 1st through June 20th there were 161 deaths among the incarcerated in Alabama prisons, Appleseed learned through a records request. Alabama prisons saw a record 325 deaths in 2023. So far, ADOC investigations have determined that 112 of those deaths were from preventable causes, with 10 homicides, 13 suicides and 89 overdose deaths.

Alabama’s overdose mortality rate in prisons last year of 435 per 100,000 was 20 times the national rate across state prisons, according to the latest available national data from the Federal Bureau of Investigations.

Ms. Martinez estimates that during her brother’s time in prison she sent $3,000 to men who’d threatened his life. Between her, her mother and Wesley’s wife, she estimates they sent between $5,000 and $7,000 to extortionists who threatened to kill him.

“Because I was scared for his life, and even with us telling the prison, ‘Hey, there’s drugs in there. It’s not as safe there. They were like ‘Oh, well, he’s probably gonna die.’ This is literally what the woman told me on the phone,” Mrs. Martinez said of a female officer she spoke to. “She said, we’ve moved him four times already, and I said, no you have not. You moved him from one dorm to the next. You didn’t try to do anything.”

Mrs. Martinez said the Law Enforcement Services Division investigator looking into her brother’s death told the family that ADOC told him not to worry about an autopsy because they believed it was an overdose death, but the condition of his body at the funeral home told another story.

The side of Wesley’s face was black, and he had a large knot on his head. “So we started asking. How did this happen?,” Mrs. Martinez said.

The investigator told the family that he fought for an autopsy to be done because Wesley had bruises on his face, but that according to the funeral home there were no signs that an autopsy had been done.

“We had my brother cremated, so there’s no going back. They just ripped that away from us. We thought an autopsy was performed because the investigator didn’t even know the autopsy wasn’t even done,” Mrs. Martinez said.

Wesley had an addiction problem and may have been using drugs while incarcerated, Mrs. Martinez said. She believes he was in debt to those men inside who were selling him drugs. Drug debt is a common catalyst for violence and death inside Alabama prisons.

One incarcerated man who was extorting the family told Mrs. Martinez on a prison phone about a month before her brother died that, “We run this prison. The officers do what we say, so they’re not going to protect your brother.” Like so many Alabama families with incarcerated loved ones, Wesley Abernathy’s family did not know who to turn to, or how to create safer conditions for him. There is no guidebook for desperate families and generally no one with any power to help them. “There are people that deserve to be in there. I understand that, but it’s to teach people. Not for all these families that have to get phone calls that their family member is gone.”

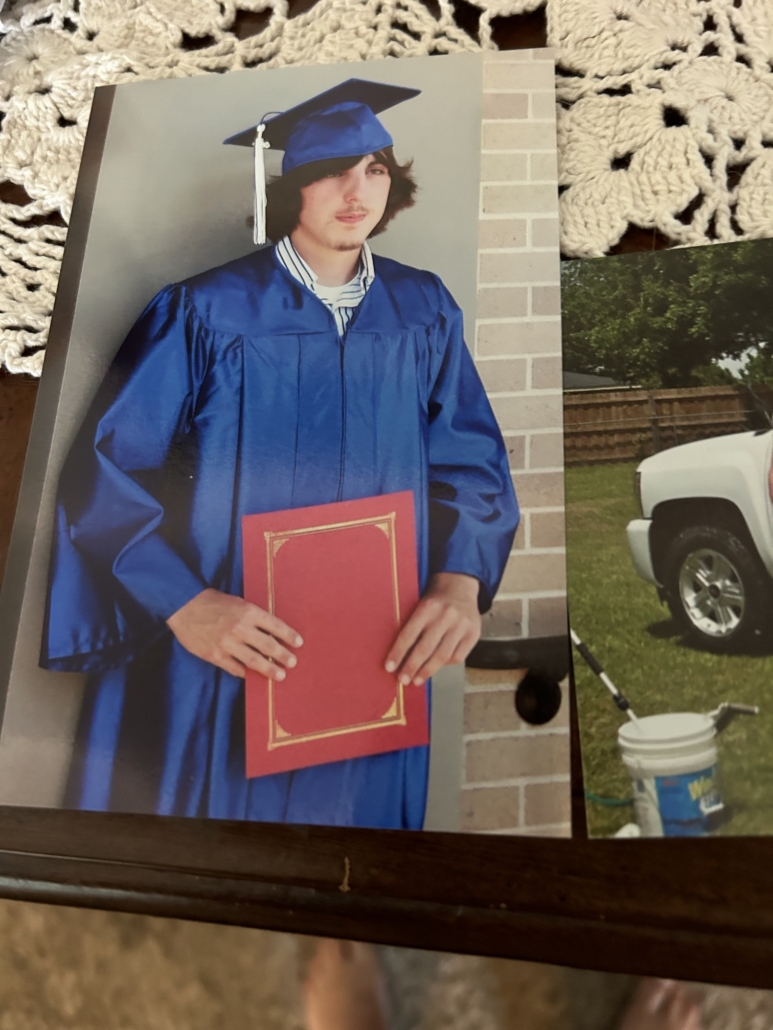

Wesley and his wife, Amber Abernathy (photo courtesy of the family).

Mrs. Martinez described her brother as a good-hearted person who loved to fish, and could most often be found fishing at Guntersville Lake. “He was a good man. He had three babies, and he loved them to death, with everything in him,” Mrs. Martinez said.

Amber Abernathy, Wesley’s widow, told Appleseed she received a call from the prison warden the morning he died, but that the shock of finding out had her in disbelief.

“I was just saying, Is this a joke? Are you just kidding? This is not funny. I just was in panic,” Mrs. Abernathy said. The warden told her there was no bruising on the body and that it appeared to have been a medical event.

Mrs. Abernathy described what the family saw when they arrived at the funeral home.

“He had lots of bruising on his face – on the right side of his face. He had a knot on the right side of his head, and markings behind his ear and on his right side,” Mrs. Abernathy said. “We were not prepared for that.”

The Law Enforcement Services Division investigator assigned to her husband’s death told her in an early phone call that they believed he died of a fentanyl overdose, she said, and that there were no bruises or other signs of injury on him. She said that although she suspected he was using drugs in prison he’d never take fentanyl purposefully, and that he had always been afraid of that drug. The investigator told her his body would be set for an autopsy, but that’s not what happened, she explained.

Mrs. Abernathy said the investigator told her Wesley could be seen on security footage at around 3:30 am the day he died doubled over in pain, before going to the bathroom where he remained doubled over as if his stomach was hurting. He then returned to his bunk. A man who slept nearby Wesley later told the investigator that when Wesley returned from the bathroom he told the man he believes he may have ingested fentanyl. She said the family knows he bought a cigarette from someone the night before and they’re worried that it may have been laced with a drug.

In another call with the investigator about three weeks after the funeral he told Mrs. Abernathy that he had seen those bruises and had requested an autopsy, Mrs. Abernathy said, but when she explained to the investigator that the funeral home told the family they saw no signs of an autopsy having been done, the news caught the investigator off guard.

Wesley and his daughter, Paizlee Abernathy (photo courtesy of the family).

“That doesn’t make sense, because I specifically requested for a full autopsy on him. They had his body at forensic sciences, so I don’t understand why they didn’t do an autopsy,” Mrs. Abernathy said the investigator told her, referring to the Alabama Department of Forensic Sciences (ADFS), which can conduct full autopsies and drug toxicology screens on incarcerated people.

Mrs. Abernathy requested the report on her husband’s death from the ADFS but in a letter to her on June 20th, and in an identical letter on July 19th, the department said the reports in that case weren’t yet public records because the death was either still under investigation by the local district attorney, or because the department hadn’t yet finalized the reports.

ADOC declined to directly answer Appleseed’s questions regarding the statement the investigator made about his concerns over the signs of injuries and his request for a full autopsy.

“The death of inmate Abernathy is still under investigation by the Law Enforcement Services Division. The ADOC does not have the authority to authorize autopsies. Any questions regarding autopsies should be directed to the Alabama Department of Forensic Sciences,” the ADOC spokesperson wrote to Appleseed.

ADFS in a response to Appleseed also didn’t answer whether Wesley received a full autopsy or just a toxicology screening, and instead sent a letter identical to those sent to Mrs. Abernathy.

ADOC first confirmed for Appleseed that autopsies would no longer be done by the state for suspected natural or overdose deaths. UAB Hospital terminated its longstanding agreement with ADOC to conduct autopsies and/or toxicology screens on suspected natural and overdose deaths on April 22, 2024, ADOC told Appleseed. Families recently filed a lawsuit against UAB after discovering that their incarcerated loved ones’ bodies were returned to them for interment missing internal organs.