by Eddie Burkhalter, Researcher

St. Clair Correctional Facility (photo by Bernard Troncale)

Alabama prisons in 2023 saw record high deaths for a second straight year, a grim reminder that the Alabama Department of Corrections is incapable of protecting incarcerated people from drugs, violence and death.

Last year, 325 people died in Alabama prisons, the Alabama Department of Corrections confirmed for Appleseed. This total means more than 1,000 people have died in state prison custody since 2019 when Alabama government officials were put on notice of conditions so dangerous and deadly that the state was violating the U.S. Constitution’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment. Altogether, there were 1,045 deaths in Alabama prisons from the April 2019 release of the U.S. Department of Justice’s report detailing the horrific violence in the state’s prisons through the end of last year, according to ADOC’s statistical reports and data Appleseed gathered through records requests.

ADOC doesn’t release timely data on prison deaths, and names aren’t released in department reports, leaving it up to journalists and others to gather those names and seek confirmation. The department’s quarterly reports publish data that reflects what was happening in prisons three months prior, so it’s difficult to gauge the current state of violence and death inside Alabama prisons. Appleseed obtained the names and dates of deaths last year through a records request.

The Public Oversight Committee held a public hearing on December 13, 2023 in Montgomery (photo by Alexander Willis for Alabama Daily News).

It can take many weeks and even months for ADOC to close out an investigation into an in-custody death, due in part to the time it takes the state’s lab to complete toxicology reports, but in ADOC’s quarterly reports the department notes that 127 death investigations had been completed for deaths that occurred in 2023. Among those, 47 were determined to be caused by “accidental/overdose,” four were homicides, five were suicides, 72 were “natural” deaths and two were “undetermined’ leaving 198 yet to have an official cause of death.

Families of victims of custodial violence and abuse increasingly are speaking up. Last month, dozens of grieving family members attended the Joint Prison Oversight Committee at the Alabama Statehouse. Other families have emailed lawmakers with chilling photos and videos of the chaotic, degrading, and deadly conditions across the prison system. The 2024 legislative session is less than two weeks away and the desperation of these families promises to push Alabama’s prison crisis into the spotlight yet again.

Hundreds of deaths, little communication with grieving loved ones

ADOC also has a history of misclassifying deaths, as the U.S. Department of Justice noted in a 2019 report. “There are numerous instances where ADOC incident reports classified deaths as due to ‘natural’ causes when, in actuality, the deaths were likely caused by prisoner -on- prisoner violence,” according to the U.S. Department of Justice’s findings in the report.

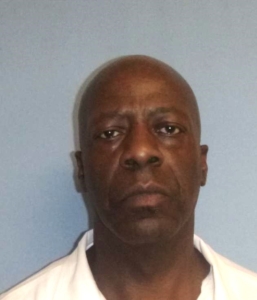

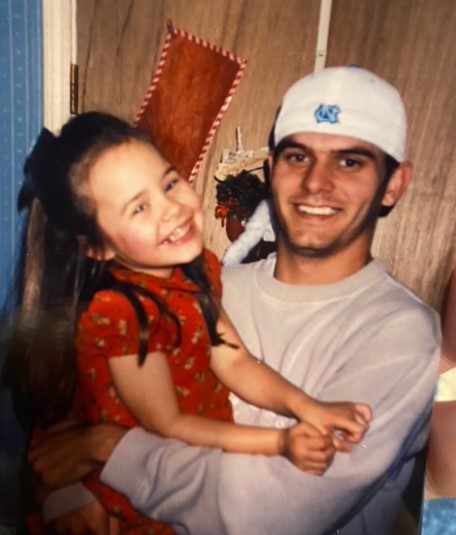

Christopher Latham (family photo)

For example, the death certificate for Christopher Latham, 40, who died on Oct. 10 following an assault by another incarcerated man at Ventress Correctional Facility on Oct. 4, lists the manner of death as an “Accident” despite also noting that the injury was the result of a “prison fight.” The death certificate, first obtained by ABC 33/40’s Cynthia Gould, lists the immediate cause of death as respiratory failure and the underlying cause as “Intracranial Trauma.” Latham had previously been struck in the head with a weight at Staton Correctional Facility prior to being taken to Ventress prison, where the second assault occurred, according to statements from his family and ADOC.

Appleseed on Thursday contacted the office of the physician who certified Latham’s death at Southeast Health Medical Center in Dothan to question how injuries from a prison fight could result in the death certificate listing the manner of death as “Accidental” instead of a homicide. The physician’s nurse confirmed that Latham had been seen by the doctor, but the physician did not return Appleseed’s message as of Monday morning.

Among the names of those who died last year are 39-year-old Rubyn Murray, who was set to be released in 2025. Former ADOC sergeant D’Marcus Sanders was charged with murder in connection with the July 2023 beating death of Mr. Murray at Elmore Correctional Facility. Mr. Murray had served 19 years of a 20 year sentence for a 2004 robbery. The Alabama Board of Pardons and Parole denied parole for Mr. Murray in February of 2021. His conviction stemmed from a robbery of a Montgomery convenience store in which $125 was stolen; no one was injured, according to court records.

Mr. Murray was involved in an altercation with another officer earlier on July 26, which resulted in minor injuries on both the officer and Mr. Murray, according to an ADOC statement. Murray was then taken to a “back gate holding area” and was to be taken to Staton Correctional Facility for medical assessment and treatment.

“Before the transport could occur and in violation of ADOC policy, two other inmates gained access to the holding area,” the statement reads. “Inmate Murray was found unresponsive and was transported to SHCU and then to an area hospital for emergency treatment. Medical staff was unable to resuscitate inmate Murray and he was pronounced deceased by the attending physician.”

Sgt. Sanders and two incarcerated men, Fredrick Gooden and Stefranio Hampton, were charged with Murder. According to court records, Sgt. Sanders unlocked Mr. Murray’s cell door and allowed those two other incarcerated men to enter and beat Mr. Murray, causing serious injuries that later resulted in his death. An Elmore County District judge has approved an affidavit of hardship filed on behalf of Sgt. Sanders and declared him indigent, meaning Alabama taxpayers will pay the cost to defend him against the murder charge.

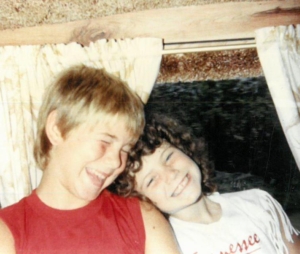

Brian Rigsby and his sister Elizabeth (photo courtesy of Pamela Moser)

Brian Rigsby, 46, died on Oct. 4, 2023, at the Staton Correctional Facility infirmary after being beaten by other incarcerated men in August 2023 at Bullock Correctional Facility, causing numerous stab wounds, fractured ribs, a facial fracture and two small skull fractures. Mr. Rigbsy also had end-stage liver failure in the days leading up to his death, his mother, Pamela Moser, told Appleseed.

Mr. Rigsby had been turned down for parole by the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles in July 2023. Ms. Moser was one of the families who pleaded with legislators to address the inhumanity in the prisons at the oversight committee meeting. “When one breaks the law, they lose their freedom, not their rights as a human being. The way my son’s end of life was handled was not humane, kind, or caring. For him and

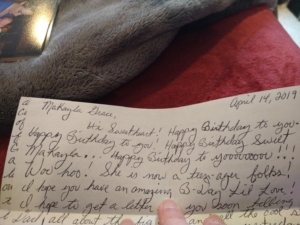

MaKayla Mount holds an urn containing her father Christopher Mount’s ashes at the Prison Overrsight Committee’s public hearing (photo by Eddie Burkhalter)

his family, I can only hope and pray for change,” she told the six lawmakers in attendance.

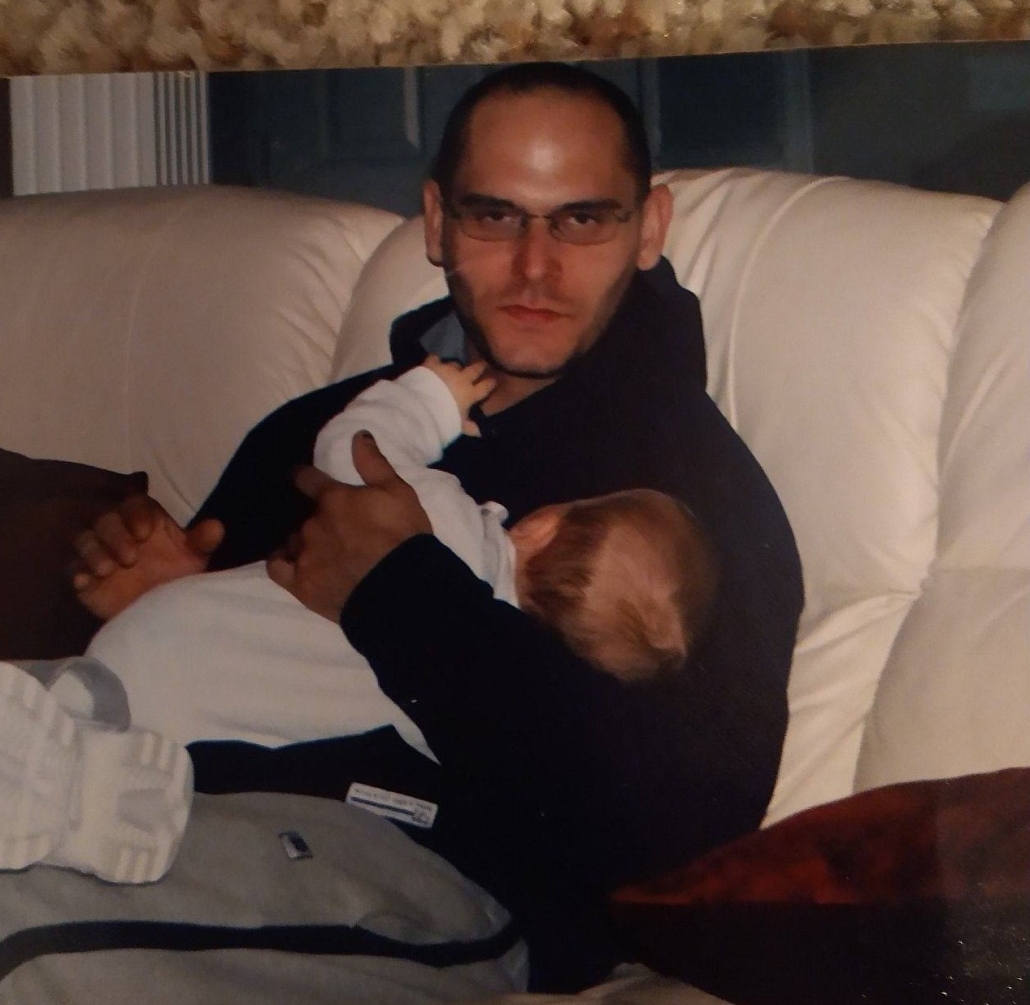

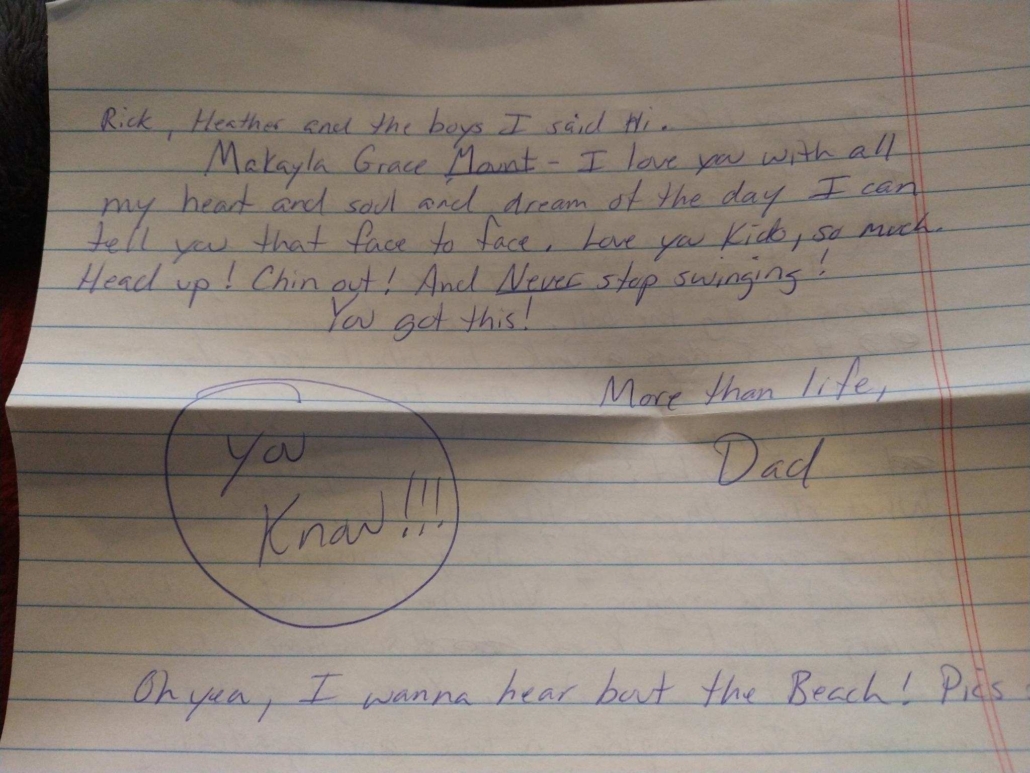

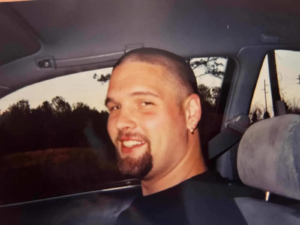

Another 2023 victim was Christopher Mount, 44. He was beaten and strangled to death on Mother’s Day 2023 after being placed

in a suicide cell with another man at Easterling Correctional Facility.

Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) investigators believe the other man, William Smith, killed Mr. Mount in that cell. Mr. Smith, 48, was incarcerated after being convicted of choking his girlfriend to death in 2017. Mr. Mount was choked to death as well, according to his death certificate, which lists his cause of death as asphyxiation. “My daughter has nightmares and wakes up screaming and crying because all she sees is her dad being beaten and strangled and screaming for help,” Christy Martin, mother to Mr. Mount’s 17-year-old daughter, MaKayla, told Appleseed. “We were supposed to have him home in our arms and not in an urn.”

Easterling prison was at 188 percent capacity the month that Mr. Mount was killed.

Alabama’s prison mortality rate is five times the national average

The November 2023 death of 22-year-old Daniel Williams following what other incarcerated men say was two to three days of beatings and sexual assaults received international news coverage. Mr. Williams was serving a 12-month sentence and was weeks away from his release when he died.

The suspect in Mr. Williams’ death had a decade-long history of assaulting and raping other incarcerated men in several prisons, Appleseed’s review of court records revealed.

Those documents show nine reports of the suspect in Mr. Williams’ death sexually assaulting or harassing other incarcerated men over the last five years, and those records also show that ADOC didn’t take disciplinary measures against the man that could have increased his classification status and removed him from areas inside prisons in which he could further harm others.

In October 2023, ADOC gave the suspect a perfect scores in the category of “History of Institutional Violence” despite clear records of the previous assaults and rapes. As of Jan. 9 the suspect had not been charged in connection with Mr. Williams’ death, according to court records.

The federal government in December 2020, sued the state and the Department of Corrections alleging that the state “fails to provide adequate protection from prisoner-on-prisoner violence and prisoner-on-prisoner sexual abuse, fails to provide safe and sanitary conditions, and subjects prisoners to excessive force at the hands of prison staff.” That lawsuit is scheduled for trial in November, 2024.

The death rate in Alabama prisons has climbed to five times the national average. Alabama’s prisoner mortality rate is 1,370 deaths per 100,000 people, compared with a national average of 330 deaths per 100,000, according to the U.S. Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics.

The Ivey Administration’s response has been to begin construction of a $1.08 billion prison expected to house 4,000 people when it opens in 2026. ADOC officials cite perennially low staff and inability to retain and recruit officers as the cause of much of the violence, but have not released a realistic plan as to how they plan to staff the largest prison ever built in Alabama.

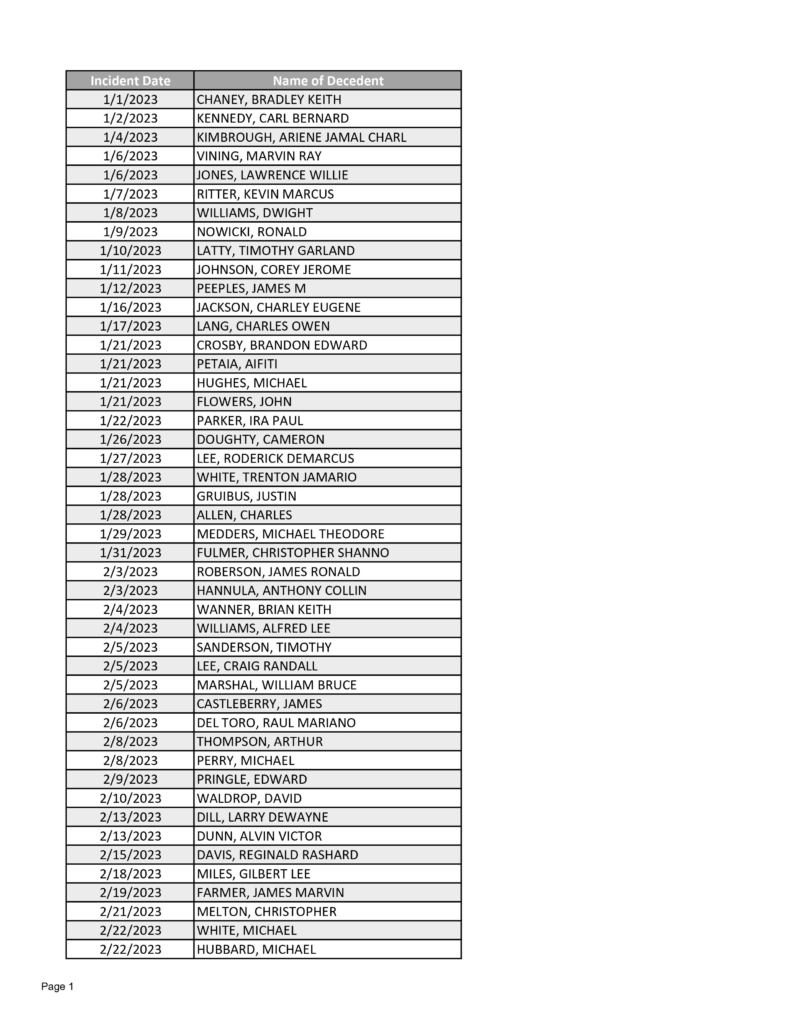

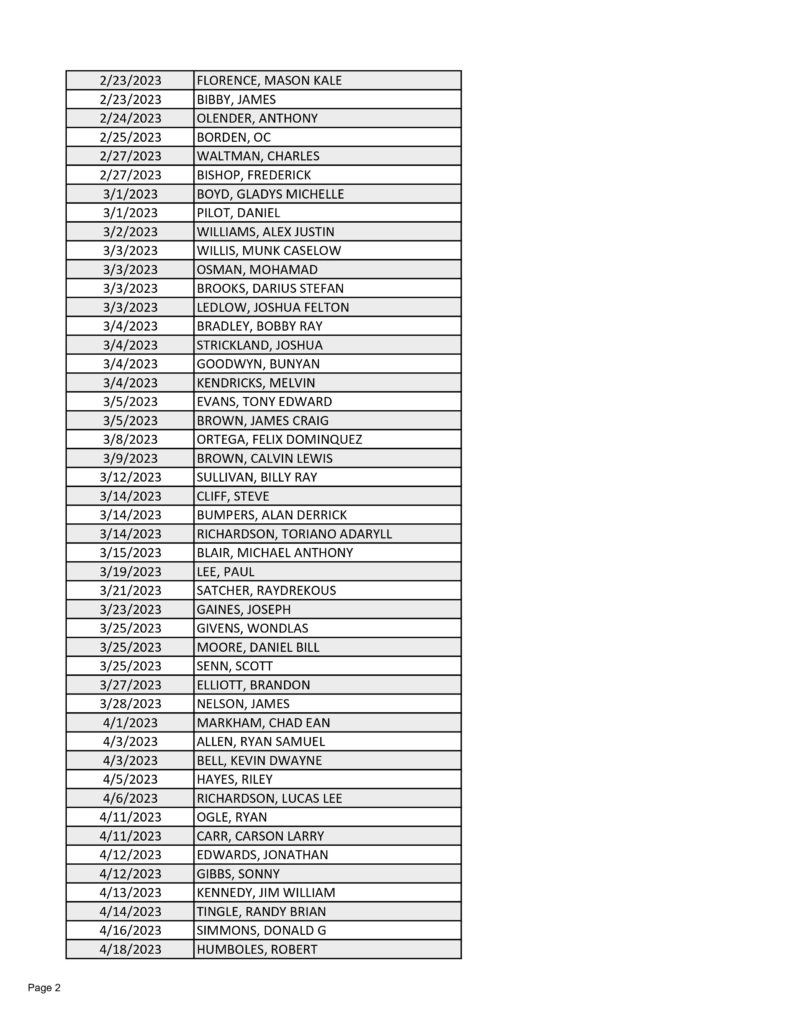

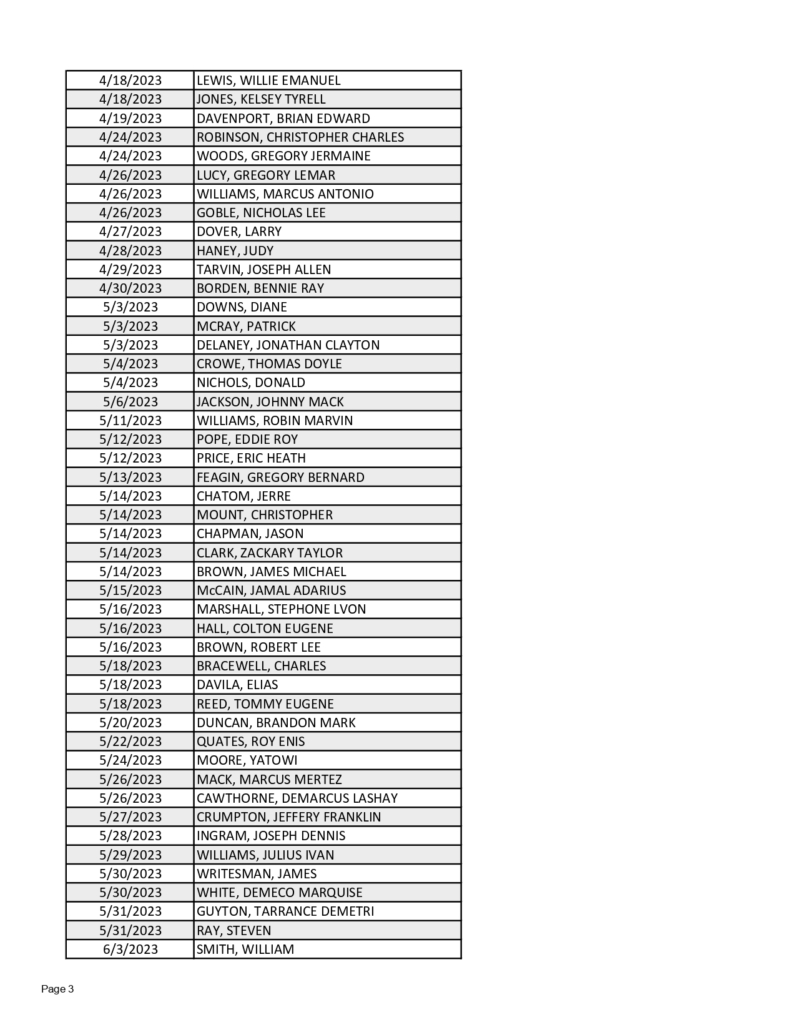

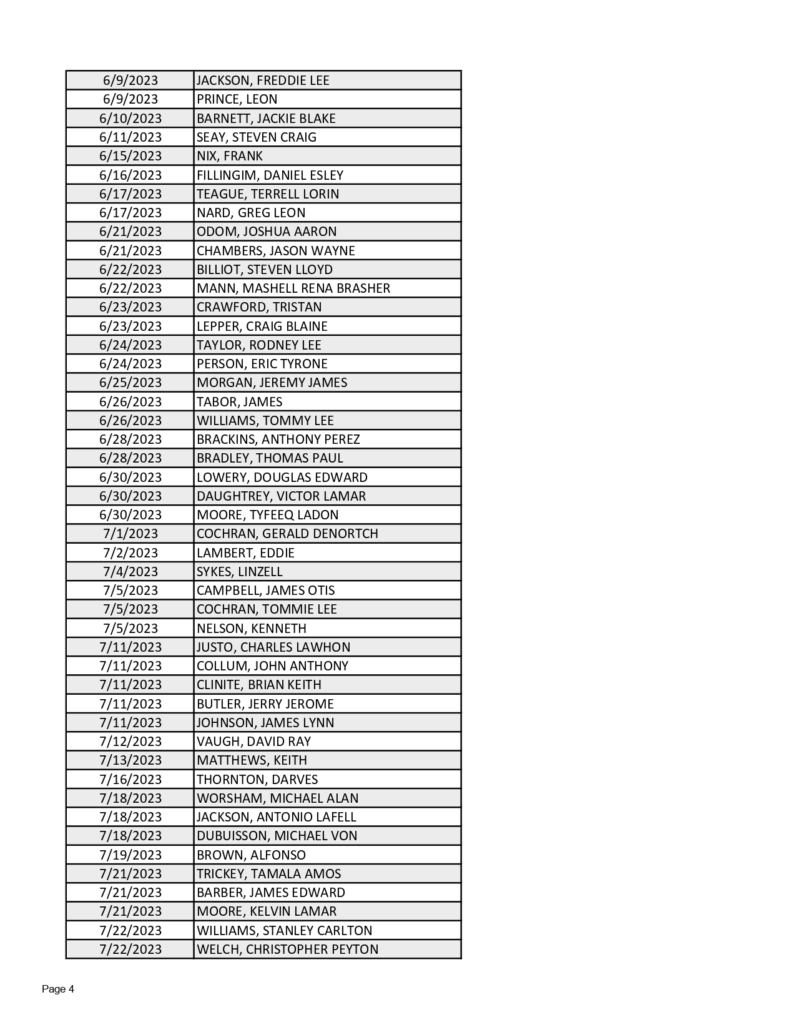

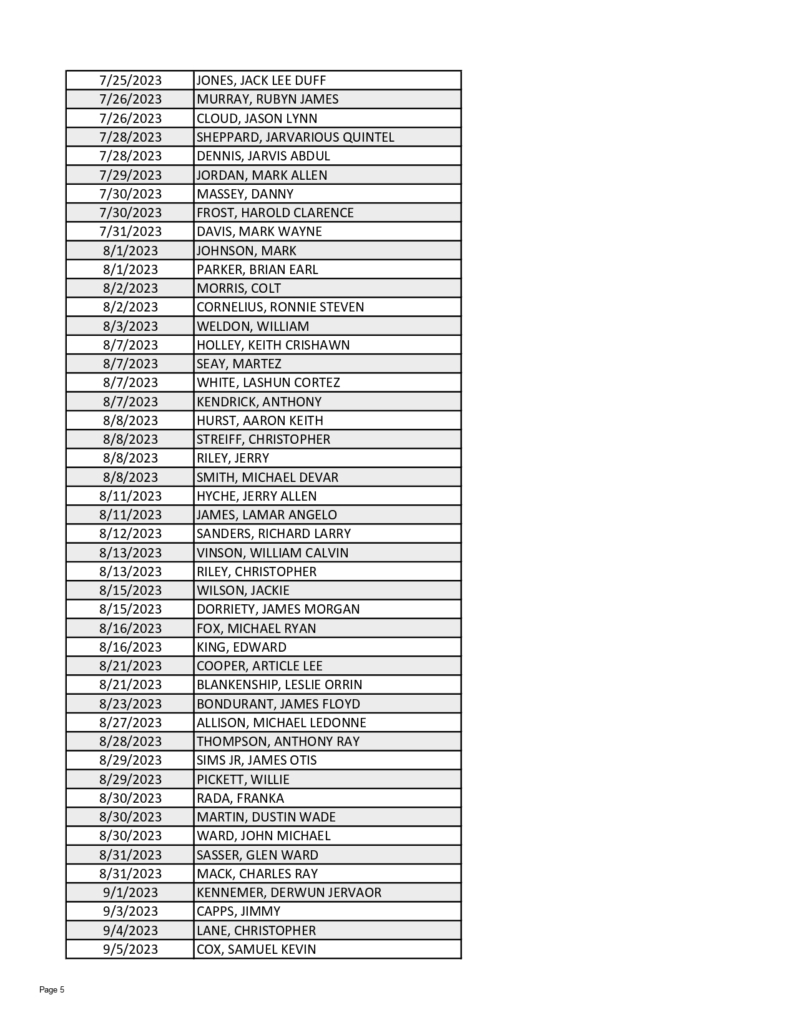

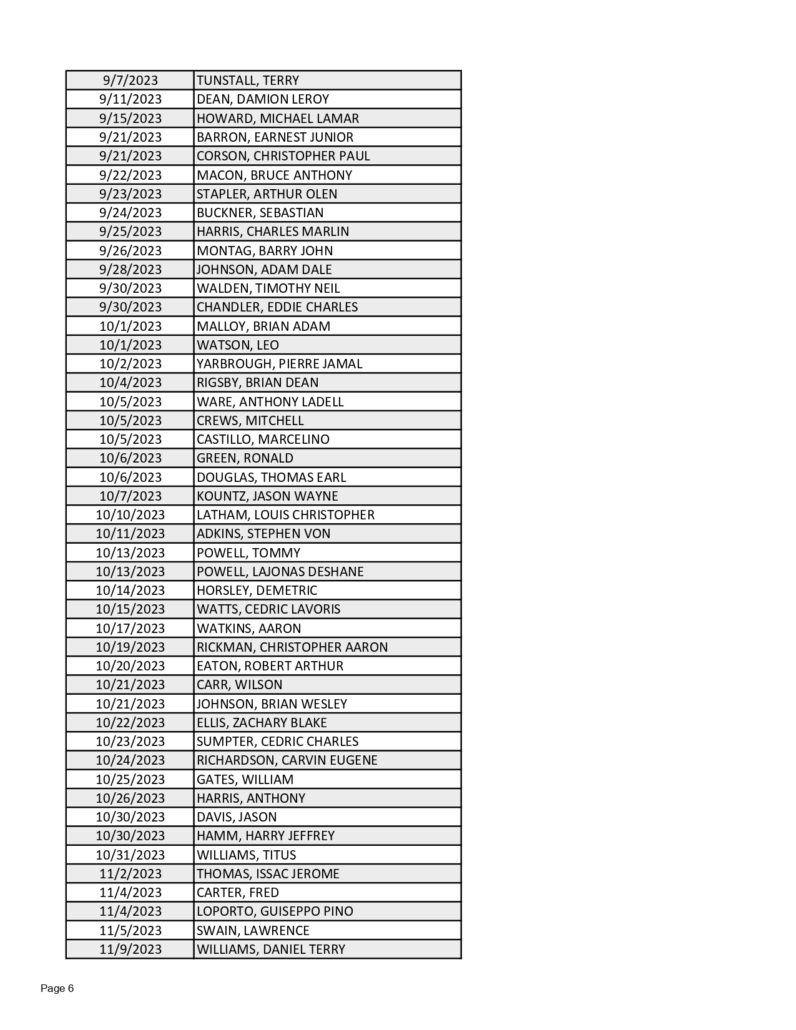

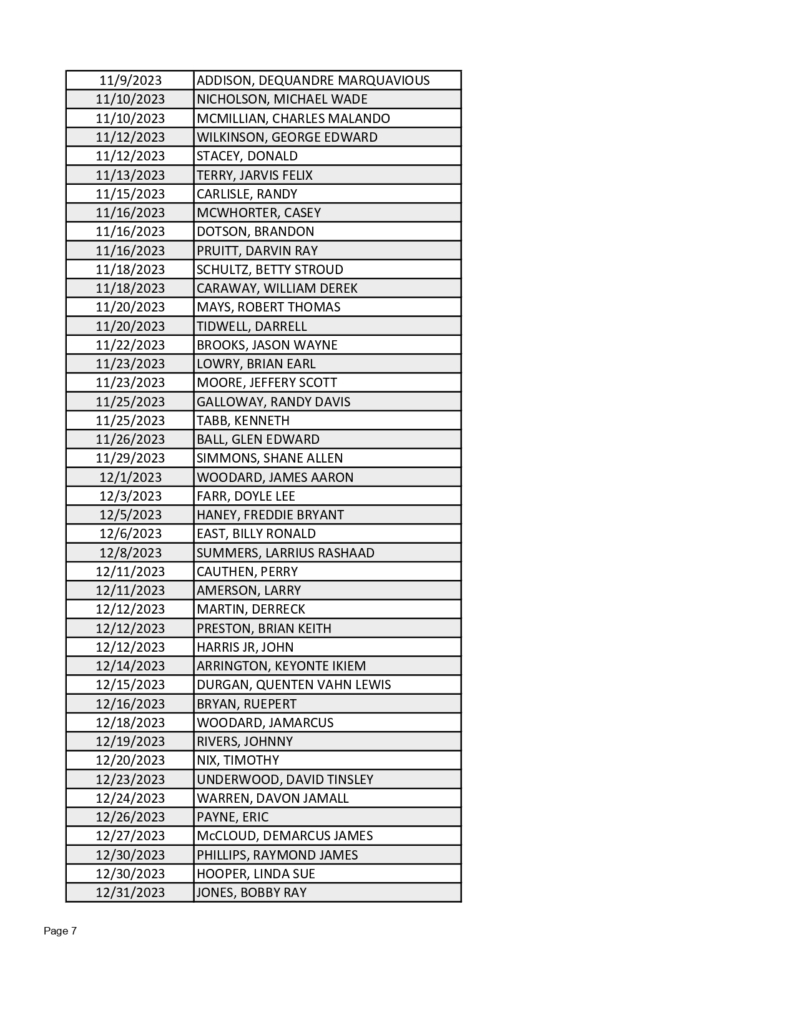

The following is the document provided by the Alabama Department of Corrections listing deaths in 2023: