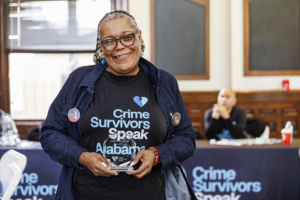

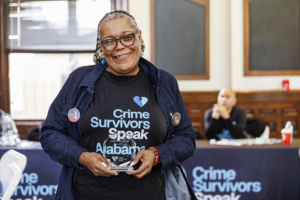

Appleseed’s Callie Greer, honored with a Lifetime Achievement Award by Crime Survivors Speak

Callie as she receives her lifetime achievement award. Photo by James Gilbert

Appleseed’s Callie Greer, honored with a Lifetime Achievement Award by Crime Survivors Speak

Callie as she receives her lifetime achievement award. Photo by James Gilbert

Alabama Appleseed has been featured in the prestigious Chronicle of Philanthropy!

Here’s what they’re saying:

“In a state dominated by a Republican supermajority and long resistant to criminal-justice reform, Alabama Appleseed has become one of the South’s most unexpectedly effective advocacy groups.”

The article traces Appleseed’s leap into legal and reentry services, beginning with the case of Alvin Kennard, our first client freed from a life without parole sentence.

“When Carla Crowder walked into a Jefferson County courtroom in August 2019, she didn’t expect to change the direction of her small nonprofit, the Alabama Appleseed Center for Law and Justice. She was there for one man: 58-year-old Alvin Kennard, who had spent 36 years behind bars for stealing $50.75 from a bakery in 1983 at age 22. His three earlier felonies — burglaries he committed at age 18 — meant he was sentenced under Alabama’s notoriously harsh “three-strikes” law, which mandates life without parole even for a low-level offense in which no one is physically harmed.

Crowder’s group hadn’t taken on individual clients before. The tiny policy and advocacy shop she had joined just months earlier was built to study and reform the state’s criminal-justice system, often through data-driven reports. But when a judge asked her to represent Kennard, she agreed — and when he was released, the story ricocheted nationally. That moment reshaped the organization’s sense of what was possible.”

We are so grateful for our funding partners at the National Football League who invested in this work early on, and now more than 30 Alabamians are freed from draconian sentences.

A group of Appleseed’s clients, all of whom served decades in life sentences without parole in Alabama prisons, enjoy a day in a Birmingham park following a birthday celebration for John Coleman. From left are Larry Garrett, Ronald McKeithen, Robert Cheeks, Lee Davis, John Coleman, and Willie Ingram. Photo by Bernard Troncale

The story goes on:

“Crowder used the funds to hire a newly minted lawyer, and together they began combing through spreadsheets and legal files. Their next case was Ronald McKeithen, who had served 37 years for a robbery he committed at age 21. After his release, he joined Appleseed’s staff and remains a core part of its re-entry team.

As more people were freed, more letters poured in from others seeking help. “Nobody else was doing these kinds of cases anymore,” Crowder said. “By taking individual cases, we’re both filling such a huge gap in legal services and learning about the brokenness of the system from their stories.”

Read the full story: How Unlikely Allies Help One Small Nonprofit Get Results in a Deep Red State

An Appleseed-supported bill that would bring more fairness to the parole revocation process and help prevent unnecessary revocations that do not contribute to public safety has been filed in the Alabama Legislature.

SB254, sponsored by Sen. Sam Givhan, R-Huntsville, would give the parole board greater discretion when someone on parole is arrested for a minor offense or when they have committed technical violations. Current law mandates revocations in many of these kinds of cases. The rigidity of the existing statute has resulted in people with long histories of employment and compliance being returned to Alabama’s crowded and violent prisons unnecessarily.

SB254 was developed after years of research and communication with incarcerated Alabamians. Appleseed shared some of these stories in our Taking a Life report, which documented people across the state who were living successful lives and meaningfully contributing to the workforce, then sent back to prison on a parole revocation despite having no new convictions.

This common sense bill:

Among the people impacted by this bill are Archie Hamlett and Vinson French, both men in their 50s, who were incarcerated under life sentences for nonviolent crimes, then eventually released on parole. They spent years working and contributing to their communities, then were arrested on new charges that never resulted in convictions..

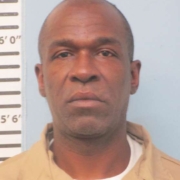

Mr. Hamlett now, following revocation

Archie Hamlett at his home in Hazel Green before his parole was revoked last year.

Mr. Hamlett, who is 53, is currently trying to manage his trucking company, Hamlett Logistics, from Easterling Correctional Facility. He was paroled from prison, where he served decades on a marijuana trafficking conviction, and was a successful business owner and homeowner. Last January, Madison County deputies pulled him over as he drove home on icy roads after suspecting he was driving under the influence. While he was detained on the side of the road, he requested to retrieve a urinal from his truck; Mr. Hamlett has a documented medical condition. The deputies declined that request, and he urinated beside his truck. He was charged with public lewdness, a misdemeanor that was later nolle prossed on a motion by the state, meaning they declined to prosecute the case, noting that he was already returning to prison through mandatory parole revocation. SB254 would have provided the parole board discretion to consider all of the circumstances involved in his arrest, including his medical condition, the minor nature of the public lewdness charge, the behavior that contributed to that charge, and any recommendations from his parole officer. When the charges were nolle prossed by the state, Archie’s revocation would have been revisited by the board.

Mr. French, who is 59, has not committed a new felony in 35 years. While at work in 2020, he was charged with theft because he was sitting in a truck near a trailer filled with stolen scaffolding. A Montgomery County District Court Judge quickly dismissed the charges for lack of probable cause and ordered him released. However, his parole had already been revoked and he was transported back to prison. For more on the frustrating chain of events that have left Mr. French languishing in prison as he nears age 60, please read our report, Taking a Life: With life sentences, the State of Alabama controls thousands of rehabilitated individuals long past the point of danger, until death. But why?

By Eddie Burkhalter, Appleseed Researcher

More than six years after the State of Alabama was put on notice that its violent and dangerous prisons violate the United States Constitution, the death toll inside state prisons was nearly three times the national average.

At least 202 people died inside Alabama prisons in 2025, Alabama Appleseed discovered through a records request to the Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC). Alabama’s prisoner mortality rate in 2025 was 957 deaths per 100,000 people, compared with a national average across state prisons of 330 deaths per 100,000, according to the U.S. Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics.

That was a drop from the 277 deaths in Alabama prisons in 2024, following another slight decline from the record high 327 in 2023. While the decline can be considered progress, the rate of deaths across Alabama prisons dramatically exceeds the death toll in other state prison systems, and continues to be high despite multiple commissions, committees, hearings, lawsuits, and investigative reports.

That was a drop from the 277 deaths in Alabama prisons in 2024, following another slight decline from the record high 327 in 2023. While the decline can be considered progress, the rate of deaths across Alabama prisons dramatically exceeds the death toll in other state prison systems, and continues to be high despite multiple commissions, committees, hearings, lawsuits, and investigative reports.

Tim Mathis speaks before the Legislature’s Joint Prison Oversight Committee. Mr. Mathis is one of hundreds of Alabama parents whose children have died in state custody.

The extraordinary loss of life inside prisons run by the largest law enforcement agency in the state has left families devastated and searching for answers. Often families are notified of these deaths by a warden who shares little detail about how the person died. That’s in part because UAB Hospital terminated its longstanding agreement with ADOC to conduct autopsies and/or toxicology screens on suspected natural and overdose deaths on April 22, 2024.

Therefore, while we know how many people died, getting an official account for how they died is more difficult. A 2021 state law requires the department to publish a quarterly report containing statistical data on the number, manner, and cause of inmate deaths occurring in prisons “including the results of any autopsy provided to the department by a third party.” ADOC began including a section labeled “Final autopsy results” in those reports. However, without stating a reason, the department removed that section from the reports beginning with the last quarterly report in 2022, despite the reports still containing the phrase that “the final autopsy results reflect the opinion of the medical examiner conducting the autopsy of the final cause of death.”

The lack of transparency surrounding these deaths is all the more alarming given ADOC and the state’s years-long legal battle over the unconstitutional treatment of incarcerated men. The U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division in 2019 released its first report detailing the out-of-control prisons for men in Alabama, The federal government in December 2020 sued the state and ADOC alleging widespread use of force, corruption, rampant drugs and contraband, and the inability of ADOC to keep men safe from sexual and physical violence and death.

More than 1,500 Alabamians have died in state prison custody since Alabama’s elected officials were put on notice by the federal government that state prisons were plagued by mismanagement, corruption, understaffing, nonexistent investigations, and violence, including homicides and sexual assaults.

Alabama Appleseed’s own project to track and publish state prison deaths began in 2024 and the initial batch of data we have collected has been included in UCLA Law’s data. (Individual-level data on Alabama prison deaths in 2024 can be found by visiting UCLA Law’s Github site and navigating to the raw data for Alabama. The project will soon add Appleseed’s 2022 data to the site.)

Despite the lack of transparency surrounding the causes of death, through Appleseed’s own tracking of these deaths, from news accounts and a review of a list kept by a group of advocates, Appleseed believes at least seven people died as a result of homicides inside state prisons in 2025. That’s only one less than were killed in 2024. In 2023, the record high year of deaths, there were 14 homicides in Alabama prisons.

Among those 2025 deaths were Michael Thomas Jones, 47, who died on February 6 after a previous assault at Limestone prison, and Cordel Ladon Battle, 30, died from a stabbing at Donaldson prison on Feb. 11.

Montavius Banks, 31, died on June 6 after an assault at Limestone prison. Antwion Webb, 45, died on Oct. 13 after an assault at Donaldson prison. Kendall Stone Kent, 25, died on Oct. 21 after being assaulted on Oct. 7 at Easterling prison.

Mikheal Christopher Gilliam died on Oct. 30 following a stabbing at Elmore prison. Eric Dewayne Sanders died on Dec. 9 after being assaulted at Elmore prison.

So far in 2026 there have been at least 12 deaths in Alabama prisons, according to the list kept by the group of advocates. Appleseed is working to confirm those deaths.

By Eddie Burkhalter, Appleseed Researcher

William Thomas was found hanging inside his segregation cell at St. Clair Correctional Facility on Aug. 7, 2023. Although he lived, he’s still fighting to get his life back from the severe brain injury that has robbed him of his speech and mobility.

Though William eventually was released from the hospital through a medical furlough and returned to his parents’ Huntsville home, he needs constant care and is unable to stand or fully communicate. His condition has thrust the Thomases into an ever-expanding community of families across Alabama with loved ones who emerged from state prison custody in previously unimaginable conditions: debilitating injuries, post-traumatic stress disorder, even coma.

It was another incarcerated person, not prison staff, who called Tanisha Thomas, William’s mother, and told her that her son had been found hanging from a light fixture in his cell. He had requested to be placed in a segregation cell to be safe from the physical abuse he was suffering, and to get away from the drug addictions fueled by the narcotics inside the prison, his mother said. The family believes that his hanging was either the result of hallucinations he may have been experiencing due to drug withdrawals or someone else may have tried to kill him.

William Thomas before incarceration

At the time, the family drove to UAB Hospital in Birmingham and eventually was able to visit with William, who had been placed in a medically-induced coma. He was hooked to a ventilator. The family received very little information about her son from hospital staff, who were limited in what they could say by prison officials, she said.

“Palliative care came out to me a few days later and tried to convince me to just make him comfortable, that he’s not going to be the same person. It’s not going to be a good ending. Don’t let him suffer, and all that, and my religious belief is the complete opposite,” Mrs. Thomas said. “I’m not the giver, nor the taker, of life, so I wasn’t going to make that decision.”

As her son began to improve, he was eventually taken off of the ventilator and breathing on his own. “He opened his eyes on command. I told him, ‘Son, if you hear me, let me know you hear me. Just open your eyes.’ He opened his eyes,” she said.

Tanisha Thomas comforts her son, William Thomas, who suffered severe injuries after being found hanging in his cell at St. Clair prison.

About a month after his injury, the family got a call at their Huntsville home from the hospital asking what they wanted done with his belongings. It was a confusing call, then they learned William was being sent back to the prison system where he nearly died. “Unbelievable. It was unbelievable,” Mrs. Thomas said.

His condition deteriorated once back in St. Clair prison’s infirmary. They’d visit him every Saturday that visitations were held. “Every time we saw him, he was getting worse and worse. His arms were contracting. He started losing his fingernails. He was losing his hair. He wasn’t even 100 pounds,” Mrs. Thomas said.

A social worker with YesCare, the medical provider under contract with the Alabama Department of Corrections, began the process of getting William released on a medical furlough, but that process was dragging. A correctional officer who knew someone connected to the nonprofit Redemption Earned suggested William might be a good candidate for release, and Redemption Earned reached out and took him on as a client. He was paroled in April 2024 and was sent to a Birmingham nursing home in May of that year.

William Thomas with his father and his son. Multiple generations of the Thomas family provide support to William.

William just recently began receiving Medicaid, which only pays for some medical costs incurred up to three months prior, so Mrs. Thomas is still dealing with his medical bills, and because she has to care for him day and night, she’s unable to work. Her retired husband went back to work but has only been able to find a part-time job. It’s been difficult getting her son the kind of therapy she hopes will help him get more of his life back.

The TIRR Memorial Hermann Hospital in Houston, Texas specializes in providing therapy for patients with catastrophic brain and spinal cord injuries. The family is raising funds to get him flown to the Texas hospital.

“We know he won’t be the same, but we hope he gets a better quality of life,” Mrs. Thomas said. He is improving since he’s been home, she said. The two have worked out a way to communicate, and he’s able to move his arms and legs on command.

“I try to ask him yes and no questions. So we’ve developed a process of where he blinks several times for yes and he doesn’t blink at all, or maybe once, for no. I’m a drill sergeant, and I told him, you know, I’m not gonna give up. We’re gonna keep going. We’re gonna keep going,” Mrs. Thomas said. She had advice for others who have loved ones inside an Alabama prison.

“If they have a loved one in the prison system, no matter what their demons are, do not abandon them. I know most of the time the demons are drugs, and there is a major expense with that,” Mrs. Thomas said. “But don’t abandon them. They need a voice. They need an advocate to fight for them.”

William Thomas, pictured during healthier times, with his father and son.

William was incarcerated after a 2019 parole violation. His original conviction was for first degree-robbery in 2013, for which he was sentenced to 15 years. He would have been eligible for parole consideration in June 2025, a year and nine months after he was found in his cell.

There were times while her son was incarcerated that she’d call the prison seeking a welfare check on William, only to later learn the officers who did the check mistreated him for having to conduct the check, she said. Today, the struggle for her is to try and care for him as best she can. Once a gifted athlete who played football and baseball, he’s now fighting to regain basic functions. “I just wake up every day and I know my son needs me. I’m learning how to do all of this feeding tubes and catheter cleaning. I’m learning how to provide medication. Love is driving me,” she said.

By Eddie Burkhalter, Appleseed Researcher

Two officers at St. Clair Correctional Facility were treated for exposure to an unidentified substance on November 29, requiring both to be given the life-saving NARCAN treatment and one of those officers to be hospitalized, the Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) confirmed for Appleseed.

It’s unclear from ADOC’s response what the substance was, but according to information from a person serving inside the prison the officers were exposed to fentanyl.

The incident highlights the wide prevalence of drugs inside Alabama prisons, which in 2023 had an overdose mortality rate 20 times the national average across all state prisons in 2019, the last year for which the federal government has made that data available. The prison system’s overall mortality rate in 2024 was higher than that in any other state, and was nearly double that of the next highest state.

The outside of St. Clair Correctional Facility

An ADOC spokeswoman confirmed to Appleseed this week that the officers were searching an incarcerated man when they came into contact with the substance.

“They were escorted to the Health Care Unit where NARCAN was administered. One officer was sent home to rest following the incident. The other officer was transported to an area hospital for further treatment and was later discharged. Both officers are recovered and back at full duty,” ADOC spokeswoman Kelly Betts said.

Exposure to illicit drugs inside Alabama prisons is a real and life-threatening matter for the staff who work inside the dangerously understaffed prisons, and yet it’s important to note that Illicit drugs are most often brought in and sold by ADOC staff themselves, as publicized arrests and interviews with incarcerated people show. While ADOC has made increasing efforts in recent months to catch and charge these employees, drugs and the overdose deaths persist.

Records requests show 366 ADOC staff were fired between 2018 to 2023, and 134 were charged with work-related crimes, ranging from smuggling contraband to assault and murder.

Appleseed’s review of court records for the 169 Alabama Department of Corrections employees arrested between January 2020 and June 2025 statewide suggest that relatively few officers convicted of crimes serve prison sentences, with most cases instead resulting in suspended sentences, probation or pre-trial diversion. It’s important to note, however, that in misdemeanor cases for first-time offenders, such sentences would not be uncommon, and among the 79 felony cases Appleseed reviewed, several were prosecuted federally and did receive prison time.

Two men died of suspected drug overdoses at St. Clair on July 30. The next day, ADOC Lieutenant Calvin Bush was arrested and charged with trafficking fentanyl and marijuana, and promoting prison contraband. Investigators found a large amount of drugs and contraband in a filing cabinet inside the prison Bush had control of, and at a home in Odenville, where Bush lives, according to court records.

“During the search, agents recovered a significant amount of drugs and contraband, including 4,020 grams of methamphetamine, 350 grams of promethazine liquid, 340 grams of synthetic cannabinoid, nine oxycodone pills, 326 grams of sprayed paper, 156 cell phones, two cellular hotspots, 8,980 grams of marijuana, 100 grams of crack cocaine, 16 grams of cocaine powder, and 610 grams of flakka precursor powder. Additionally, a related search yielded 2.5 pounds of marijuana and 60 grams of methamphetamine,” ADOC told Appleseed in a previous statement.

Court records show that St. Clair County District Judge Brandi Hufford in September agreed to a joint motion from Bush’s defense attorney and the prosecutor to push back Bush’s preliminary hearing until Nov. 4, 2025, “to allow the investigation results to continue by agreement of both parties.” The judge approved a subsequent joint motion on November 4 and moved that hearing date to March 3, 2026.

James Jones, who was once condemned to die in an Alabama prison, took the stage at the Woodlawn Theatre and sang a love song in front of a crowd of mostly strangers last Thursday night.

It was Appleseed’s annual Celebrate Justice event, which brought together 200 Alabamians committed to Appleseed’s mission and eager to connect with like-minded people in our community.

James Jones performs alongside Ritch Henderson and Kathleen Henderson. Mr. Jones spent 43 years in prison following a robbery conviction in which no one was injured. Appleseed secured his release in December 2024.

Months ago, once we realized that James’ dream of recording music was becoming a reality, we hatched an idea that he could perform at Celebrate Justice. We were so confident, we sent invitations to supporters announcing the plan. But Mr. Jones, who is 78, is not just recovering from 43 years in prison, he’s fighting cancer and undergoing regular chemotherapy treatments that sap his energy. So we hedged our bets and noted in the promotional materials that “with a little luck,” Mr. Jones would be joining our musicians on stage.

James Jones singing lyrics he composed while incarcerated on a life without parole sentence

Thankfully, two committed people held fast to Mr. Jones’ dream, guided him through the artful process of putting his lyrics to music, and surrounded him with support – Appleseed case manager Kathleen Henderson, and her son, Americana artist Ritch Henderson. For months they practiced, meeting up in Ritch’s favorite spots in and around the Bankhead National Forest and at collaborator Brett Robinson’s, Alabama Sound Company in Montgomery. They all believed in Mr. Jones. After all, his nickname is Honkytonk.

For his song, Ritch took the lead, Kathleen sang harmony, and Mr. Jones’ joined in for the chorus.

We made a promise, till death do us part

You signed with your love and I signed with my heart,

Together, forever I thought we’d always be.

Tonight you’re in Texas and I’m in Tennessee.

Grief like a mountain, and unchanging wind.

I’ll come to Austin, and we’ll try again.

Love is a garden you simply must tend.

I’ll do anything to hold you just once more my friend.

Imagine writing these lines while trapped in prison, with no reasonable hope of ever being free. And yet, people who are thrown away in prison for sentences of life without parole manage to do all manner of hopeful things: join book clubs, learn useful trades, mentor others, create art and poetry. Appleseed has been fortunate to come to know dozens of individuals once thrown away in prison, and through our legal work and reentry support they are now free and living meaningful lives.

We believe they are worthy of celebration. Based on the response last Thursday night, plenty of our neighbors do as well.

Appleseed clients, all who were once condemned to die in prison, joined our team at Celebrate Justice.

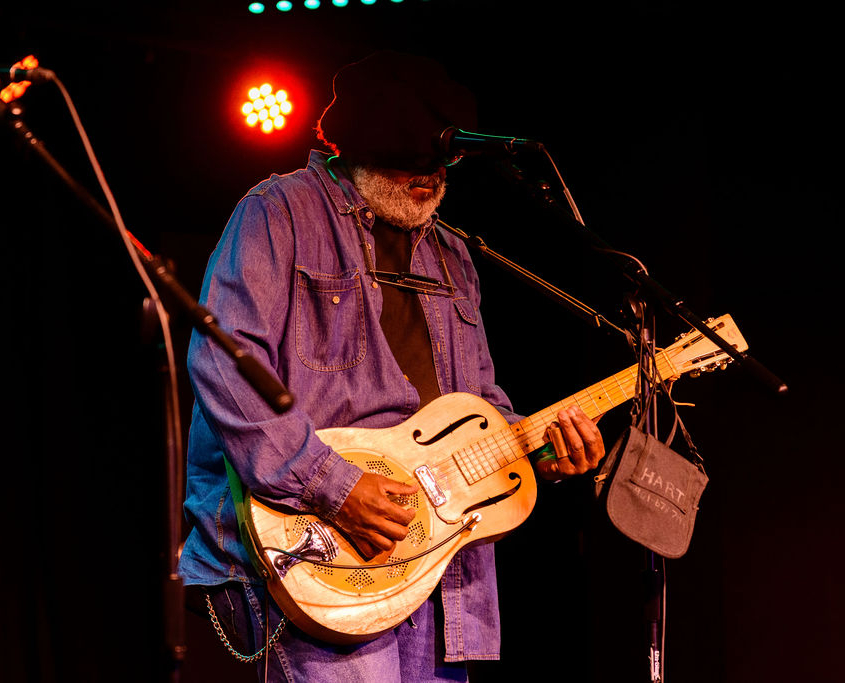

Headliner Alvin Youngblood Hart, a Grammy-winning artist, performed for the packed Woodlawn Theatre.

The generosity of Celebrate Justice supporters and sponsors ensures that Team Appleseed will continue to represent incarcerated people with extreme sentences who deserve another chance, and to provide them with the support they need once released. We are grateful for a community that believes in our work and never fails to fill the room at our events.

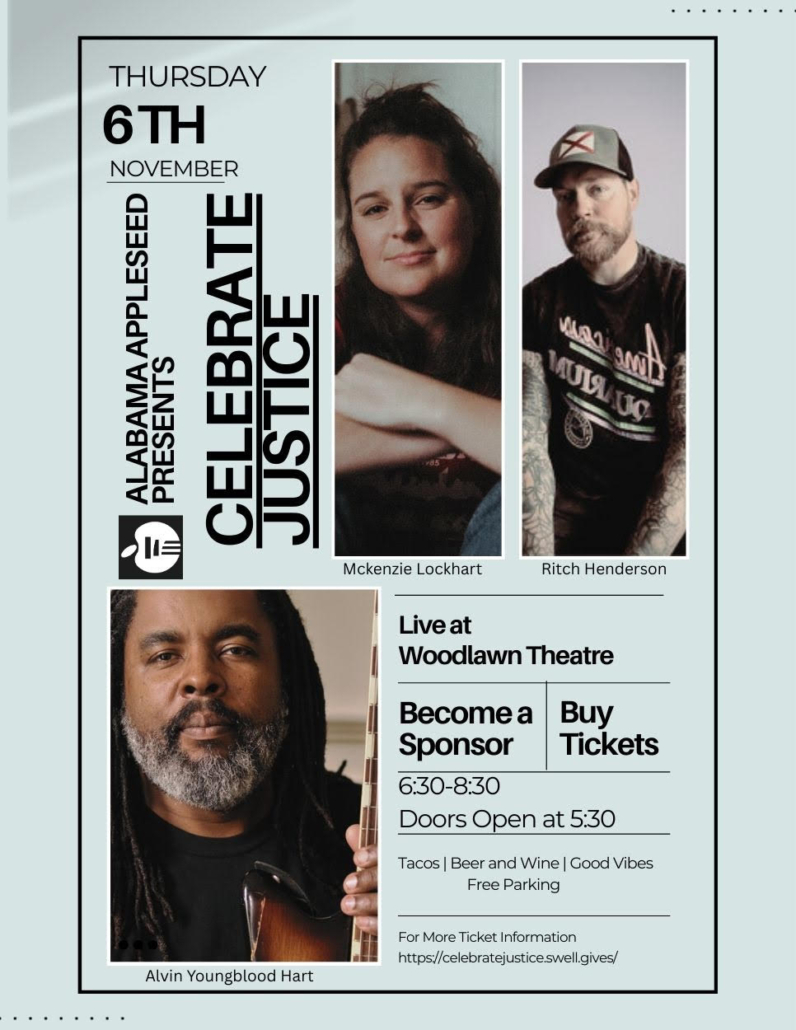

Ready to support much needed prison reform in Alabama and enjoy a joyous, musical event featuring Grammy-winning bluesman Alvin Youngblood Hart? Of course you are!

Plans for Appleseed’s annual fundraiser are in full swing. This year’s celebration centers around creating community, hope, and joy through music.

This event will bring together three amazing artists to share their talents in a casual, intimate setting. The evening will feature Shoals singer-songwriter McKenzie Lockhart, Grammy winner Alvin Youngblood Hart, and Alabama Americana singer Ritch Henderson.

Ritch and beloved Appleseed client James Jones, who is 78, are currently working on a musical collaboration. Though fighting cancer, James is determined to make the most of his freedom after 43 years of incarceration. With a little luck, we’ll be able to hear this song live for the first time!

Celebrate Justice provides needed support for Appleseed’s legislative proposals to help tackle the human rights crisis in Alabama prisons. It takes resources to create change! Support also provides housing, medical care and case management to dozens of formerly incarcerated Alabamians released through Appleseed’s legal work. (Plus you’ll get to meet these folks at the event!)

Date: Thursday, November 6, 2025.

Time: Doors at 5:30, program running from 6:30-8:30 p.m.

Location: The Woodlawn Theatre, 5503 1st Avenue North, Birmingham, AL, 35212

Come early to relax, mingle with Appleseed staff, and clients, and grab a drink and some wings, tacos, and quesadillas.

Tickets are still available at https://celebratejustice.swell.gives. If you would like to join us but are unable to purchase a ticket, please email keely.sutton@alabamaappleseed.org.

You’ll hear stories of Appleseed’s life-changing legal and reentry work, learn about our ongoing advocacy efforts, and hear about innovative research and reform happening right here in Alabama.

The evening promises to be full of good music, good drinks, good food, and the hopeful vibes we all crave. We hope to see you there!

Musician Ritch Henderson and Appleseed client James Jones work on their collaboration, assisted by studio owner Brett Robinson.

By Eddie Burkhalter, Appleseed Researcher

Anniston, AL — There are days when I have to step away from the work as my phone rings with another desperate voice, a mother crying over a son who’s been killed or overdosed inside an Alabama prison, a sister pleading for help to save a brother being threatened.

Wesley Abernathy and his daughter, Paizlee Abernathy. Eddie wrote about his death in ADOC custody last year.

I’ve spent five years taking those calls from people inside our overpopulated, understaffed, and chaotic prisons and their loved ones both as a print journalist and now as a researcher for Alabama Appleseed Center for Law & Justice, a prison reform nonprofit. I’ve met dozens of those mothers, fathers, sons, and daughters in person. I’ve seen and heard how lives are upended when our state fails to protect incarcerated people from sexual and physical violence, as all states are constitutionally bound to do.

I wish I could say that the violence and desperation I saw in the HBO documentary “The Alabama Solution” shocked me. However, the storylines in the film play out every day inside the prisons I know too well. Rehabilitation exists in Alabama Department of Corrections policy, not much in practice. Inside the unair-conditioned dorms packed with people, too many are just as likely to die inside as they are to serve the remainder of their sentences.

One tragic death at the hands of an Alabama Department of Corrections officer, highlighted in the film, reminded me of the death of 44-year-old Christopher Mount. Mr. Mount was beaten and strangled to death while locked inside a segregation cell with another man at Easterling Correctional Facility on Mother’s Day 2023. Easterling is where the film begins. Both men in these segregation cells were beaten so badly family members could hardly recognize their loved ones.

I watched as Mr. Mount’s daughter, 17-years old at the time, stood before Alabama’s Legislative Joint Prison Oversight Committee and described when she saw her father after he died. She brought her father’s ashes in an urn, but security wouldn’t let her bring the urn to the podium when she spoke: “When you see your dad for the first time in 10 years and half of his face is almost gone because he was beaten, it does something to you,” MaKayla Mount told lawmakers.

MaKayla Mount holds an urn containing her father Christopher Mount’s ashes at the Prison Oversight Committee’s 2023 public hearing.

The man who killed Mr. Mount is believed to have taken his own life 20 days later, yet another preventable death tacked onto the growing list.

“My daughter has nightmares and wakes up screaming and crying because all she sees is her dad being beaten and strangled and screaming for help,” Christy Martin, MaKayla’s mother, told me in September 2023.

I tell these tragic stories in hopes that the public sees what I see: a prison system unable to keep people safe and alive. Without the public pushing for change, there’s little hope the state’s decision-makers will choose to confront the corruption and disregard for human life currently running rampant throughout the state’s prison system. Without pressure, change is unlikely to come.

I work almost daily with families trying to protect loved ones inside Alabama prisons who are being threatened with violence. For months, I’ve spoken with a mother whose son was badly beaten and hospitalized for weeks with severe head injuries. He now finds himself in a different prison, sleeping on the floor because he doesn’t know which bunk is his and no officers will help him. Homelessness in Alabama prisons isn’t uncommon. There are images and videos taken on contraband cellphones of men curled up and sleeping on concrete floors.

Alonzo Williamson and his mother, Carol Williamson. He died in 2024 at Limestone prison and Eddie documented their story.

When an incarcerated man obtained a loaded semi-automatic pistol inside William E. Donaldson Correctional Facility on the morning of Sunday, Aug. 13 2023, I tracked the incident in real time through sources I’d developed in the prison, who reached out via social media and by phone to tell me what they were seeing. Within a few hours Derrol Shaw took complete control of the prison, and in videos taken on contraband cell phones could be seen brandishing the gun while wearing an ADOC officer’s vest. He’d held several officers at gunpoint throughout the ordeal. Ultimately, it was other incarcerated men who talked Shaw down and placed the gun outside for officers on the other side of the fences to retrieve. Lives could have been lost that day, and yet ADOC to this day hasn’t confirmed that there was a gun inside the prison that day. Appleseed was the first to report details of the incident.

Donaldson Correctional Facility in Bessemer, Alabama

I’m also building a database of prison deaths from the last 10 years, and through hundreds of records requests, a picture is forming. The picture shows uncontrolled violence, rampant drug use (most often brought into prisons and sold by staff), suicides and medical neglect.

“Deceased found unresponsive in dorm. Narcan was administered. Track marks noticed on right arm. Cause of death: Combined fentanyl, methamphetamine, and synthetic cannabinoid (MDMB-4en-PINACA),” read the details of 35-year-old Alex Justin Williams’s death on March 2, 2023, at Ventress Correctional Facility. Court records show a history of drug use. Instead of receiving treatment in prison, Williams was given easy access to the deadly drugs that took his life.

Recently, a veteran lieutenant at St. Clair prison, Calvin Bush, was arrested and charged with trafficking fentanyl and marijuana. ADOC said a search of his home turned up 100 grams of crack cocaine, 19 pounds of marijuana, 8.9 pounds of methamphetamine, and 156 cellphones. His arrest came in July, the day after 36-year-old Quarell Henry and 37-year-old Rakeivian Deet died of suspected drug overdoses at the prison where Bush was a supervising officer.

In 2023, Alabama’s overall prison mortality rate was five times the national rate across state prisons. That year, 328 people died while incarcerated in the state, a record high. Looking closer at the causes of death, the overdose death rate that year was 22 times the national rate. Of the at least 100 overdose deaths in 2023, records Appleseed obtained show that fentanyl was involved in 58.Alabama’s prison homicide rate in 2023 was 4.25 times the national rate. The suicide rate was twice the national rate, with 15 people taking their own lives.

Researcher Eddie Burkhalter, in a happier moment, joining Ronald McKeithen in picking up a newly released John Coleman from prison.

Drugs and violence are frequent threats in other prison systems, but elsewhere elected officials are held accountable and take these problems seriously. Here, we pay private lawyers to defend the state’s inaction.

I have spent countless hours making records requests and gathering documents from various state and federal agencies. Even more hours entering those names and the data of the 2023 dead into my spreadsheet. When I got to May 14, I paused and thought of MaKayla Mount, standing in front of that room full of lawmakers and attendees, and in an unwavering voice, telling the story of her father’s brutal death and what it did to her.

I recently caught up with Makayla, who is attending Jefferson State Community College on a scholarship while working full time. She earned a place on the dean’s and president’s lists for both semesters of her first year and this year was one of 40 selected among the 320 applicants to the highly competitive diagnostic imaging program at Wallace State Community College. She’s also determined to continue to help change the system that killed her father.

“My father’s death changed me entirely as a person. What began as a pursuit of justice for him has evolved into a broader mission to seek justice and reform for those who are still living within the Alabama Department of Corrections,” Ms. Mount said.

Speaking before the legislative committee was deeply personal to her. It was an opportunity to honor her father’s memory by giving a voice to those who are rarely heard.

“No one should have to live in constant fear or be denied medical care until they are at death’s door,” she said. “Everyone deserves a real shot at redemption and a fair chance to give back to the world in a positive way. A system that supports growth and rehabilitation doesn’t just help the individual. It strengthens families, communities, and society as a whole. This is why prison reform is so important to me. It’s not just about policy. It’s about humanity.”

Christopher Mount was the 119th person to die in an Alabama prison in 2023. There would be 209 more deaths that year. The next year, 277 more incarcerated lives would be lost. From January 1 through the end of June this year, at least 100 people died in Alabama prisons.

Eddie Richmond was found unresponsive on December 15, 2022 in his bed and died there at Fountain Correctional Facility.

Daniel Terry Williams, 22, was likely smothered to death on November 7, 2022 inside Staton. Eddie’s reporting revealed no charges will be filed.

Eddie has done extensive reporting on the death of Brian Rigsby and the activism of his mother, Pam Moser.

By Eddie Burkhalter, Appleseed Researcher

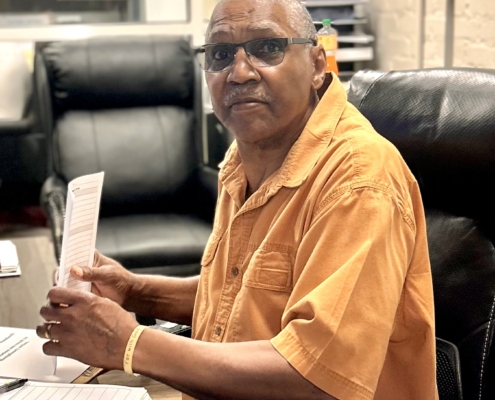

MONTGOMERY, AL — Bennie Haggins sat in a waiting area before his pardon hearing was set to begin on Wednesday in Montgomery and talked about what he hoped was to come. Only 33 living Alabamians had been on parole longer than Mr. Haggins, who was released on parole June 3, 1991, and had been under supervision with limited opportunities and movement since then.

“I’m ready to be free,” Mr. Haggins said.

Standing in front of the three-member Pardons and Paroles Board moments later board member Darryl Littleton asked Mr. Haggins, 71, what happened the day of the robbery. The board regularly asks all those applying for a pardon to discuss the circumstances around the crime that resulted in their incarceration.

Bennie Haggins, along with family members and supporters, celebrate his pardon following his successful hearing on October 8.

Mr. Haggins, 71, fought back tears and with a cracked voice explained that his childhood and young adult life were difficult. “I had no direction. I was on my own,” Mr. Haggins said. He apologized to his victim, referring to her by name. Mr. Littleton later noted that he remembered his victim’s name.

Mr. Haggins’s father abandoned the family when he was very young, and his mother followed suit when he was nine. He was raised by his grandmother and was kicked out of school in the 11th grade. Struggling with addiction, he turned to petty theft in the late 1970s. In May 1983, Mr. Haggins, in a drunken state, robbed a convenience store of $29. No one was physically injured in his crime and he was caught a short time later. He pled guilty and was sentenced to life with the possibility of parole because of his previous property crimes.

“I take full responsibility for what I did,” Mr. Haggins told the board members, and he also told them about the transformation his life took after leaving prison.

From prison, he went to work for the Sterilite Corporation in Birmingham and soon after began volunteering with the American Red Cross, which eventually hired him onto the Emergency Disaster Services team, where he would travel to weather-impacted areas and help those most in need. He spent a decade at Red Cross before being hired at the Jimmie Hale Mission in Birmingham 2022 as an intact coordinator, helping the unhoused find respite. When the weather turns freezing he drives the mission van out into the Birmingham streets looking for those who need a warm palace for the night.

“When’s the last day you’ve had off?,” Board Chair Hal Nash asked Mr. Haggins, who responded: “I don’t take days off.”

Bennie Haggins working at the Downtown Jimmie Hale Mission, where he assists with intake and with ensuring unsheltered people are provided safety and shelter on freezing nights.

Perryn Carroll, executive director of the Jimmie Hale Mission, spoke on behalf of his pardon and said that Mr. Haggins has used his past as a catalyst “both to change his life and to change countless other lives.”

“Bennie’s story is a perfect illustration of why parole is such a crucial part of our criminal justice system,” Scott Fuqua, Appleseed attorney, told board members. “And he is a shining example of what is possible when those convicted of crimes are not judged solely by their worst mistakes, but instead as a person who still possesses the human spirit and the limitless potential for positive change.”

After deliberating Mr. Haggins’s pardon application, and the pardon and parole applications of three others at the hearing, the board voted to approve a full pardon for Mr. Haggins. As of that moment he would no longer have to report to a parole officer or pay the monthly $40 supervision fee. He’d be free to vote and to travel out-of-state, something that kept him from going on cruises with his wife and daughter.

“Overwhelmed,” Mr. Haggins said after the vote.

“When I look back, I destroyed my whole life, but God blessed me with the opportunity to get it back, and I took full advantage of it and tried to help as many people as I could help, and I haven’t stopped,” Mr. Haggins said. And that won’t stop now that he’s pardoned, he said. There’s much left to do.