Alabama prison deaths reach record levels in 2022. The Department of Corrections’ response? Less reporting on deaths.

By Eddie Burkhalter, Appleseed Researcher

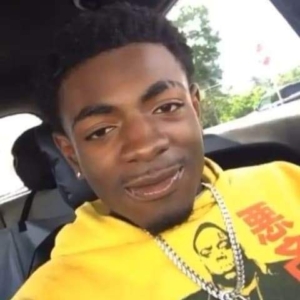

Eddie Richmond was 17 years old at the time of the robbery that led to his death sentence in the Alabama Department of Corrections.

He was not sentenced to die; the United States does not permit the death penalty for children or for individuals convicted of robbery. However, here in Alabama, prison terms routinely turn into death sentences. And 2022 was the deadliest year yet as 266 people died in government custody within Alabama Department of Corrections prisons.

Many, like Mr. Richmond, were young men serving relatively short sentences for offenses involving no physical injury to any victim. At the time of Mr. Richmond’s offense, he was not old enough to legally buy cigarettes, to join the military, to drink a beer, or to vote. Yet he was prosecuted as an adult, sentenced to prisons that have been declared so dangerous they violate the U.S. Constitution, then died six months later in prison. He was 20.

This week, news that the Alabama Department of Corrections is removing statistics about prison deaths from its monthly reports comes at the same time the Department reports the highest annual number of in-custody deaths since records have been kept.

An Alabama Department of Corrections spokesperson said that 266 people died in state prisons through Dec. 28, 2022, which is the highest death count since at least 2002, according to the department’s statistical reports. That number was provided in response to Appleseed’s questioning, not as part of a general release of information.

Those 266 deaths came to 1,330 deaths per 100,000 incarcerated people, based on the state’s prison population last year. That death rate is nearly 200 percent higher than a decade ago, a stark reminder at how deadly Alabama’s overpopulated, understaffed prisons are.

No response from prison officials

For years, state officials have watched prison deaths steadily rise, yet taken no action that has addressed the loss of life. The overall mortality rate in state and federal prisons in Alabama between 2008 and 2018 rose by 98.6 percent. Only two states had higher mortality rates than Alabama in 2018, according to a Bureau of Justice Statistics 2021 report.

In 2022, there were at least 95 preventable Alabama prison deaths: homicides, suicides, and confirmed or suspected drug-related deaths, according to investigative reporter Beth Shelburne. This is the highest number of preventable deaths since she began tracking them in 2018.

Of those 95 preventable deaths, 18 were caused by violence, five by suicide and two by either suicide or suspected overdose. Another 69 deaths were either confirmed or suspected as being drug-related, according to Shelburne’s tracking. She classifies drug-related deaths as suspected and confirmed overdoses, and deaths from disease or with prolonged or acute drug use as a major contributing factor.

It is only through the efforts of unrelenting journalists, alongside family members of incarcerated people, that the public learns about the deaths of individuals in government custody. Another source is the Twitter accounts of incarcerated activists.

Despite the surge in deaths in Alabama prisons, it’s unclear to what extent ADOC is working to address the crisis. Appleseed asked ADOC, among several questions, whether the department was looking into the reasons behind the rapid increase in deaths, or planned to do so. A department spokesperson declined to answer.

ADOC also has a history of not accurately reporting deaths, and the department doesn’t routinely release the names of those who die, or report the number of deaths in a timely fashion, requiring journalists to request confirmation on those deaths after receiving tips. ADOC’s shoddy reporting practices have drawn the attention of the federal government.

“There are numerous instances where ADOC incident reports classified deaths as due to ‘natural’ causes when, in actuality, the deaths were likely caused by prisoner -on- prisoner violence,” according to the U.S. Department of Justice’s findings in a 2019 report on Alabama prisons. In 2020, DOJ sued the State over its dangerous and understaffed prisons; the State has refused to settle and the case is headed for trial next year.

A change in reporting methods announced recently also means the public won’t get real-time information from ADOC on how many are dying in state prisons.

In its October monthly statistical report, published in late December, the department noted that the number of deaths in state prisons would no longer be published in those monthly reports, and instead would only be reported in ADOC’s quarterly reports. Yet, the most recently published quarterly report contains data that is six months old.

“How in the world do they get a hold of this stuff?”

Eddie Richmond leaves behind a devoted family struggling to get answers.

Eddie Richmond was found unresponsive on December 15th in his bed and died there at Fountain Correctional Facility

He survived what may have been an overdose at Fountain Correctional Facility on Nov. 25, 2022. About three weeks later, on December 15, he was found unresponsive in his bed and died there, ADOC confirmed for Appleseed.

“They were pretty much saying he was gone then, but he wasn’t. They were able to bring him back,” his mother, Wisteria Richmond, told Appleseed in December, speaking of that first incident in November that required an airlift to a local hospital.

ADOC did not call Richmond’s mother immediately to tell her her son was dead. Instead, as has become routine due to ADOC’s stunning indifference to the importance of informing people in a timely fashion that someone they love has died, the family first learned about his death from other incarcerated men. While he hadn’t expressed suicidal thoughts to his mother on the daily calls the two had from prison, she was worried that he might be considering taking his own life.

She expressed her concerns about her son’s well being with a prison captain but said “she really didn’t have any words for me.” The family learned from those other incarcerated men that her son may have taken fentanyl in the first possible overdose. “We had a million questions. How in the world do they get a hold of this stuff?,” she asked.

Richmond grew up with his mother in the small, rural community of Salem in Lee County. As a child, he played football, and was a talented running back and quarterback, his mother said, playing until about the eighth grade. He loved his family and his friends, and was passionate about rap music, said Ms. Richmond, who now lives in Phenix City.

Richmond was serving a three-year sentence after pleading guilty to a robbery that occurred when he was 17, according to court records. A Lee County Circuit judge denied Richmond’s request to be tried as a youthful offender, those records show.

After his release from jail on the robbery charge, and before that charge was adjudicated in court, Richmond was charged with breaking into two vehicles and two additional thefts, offenses that occurred on the same day in April 2021, according to court records.

Andrew Stanley, the attorney who represented Mr. Richmond on the robbery charge, told Appleseed that his client wasn’t alone that day in April, when the group of young people Richmond was with broke into those cars. “When I talked to Eddie in person, whether he was in jail or out of jail, he was respectful,” Stanley said, but added that was clearly hanging out with the wrong people.

Stanley explained that even without incurring the new offenses it would have been hard to get the judge to approve youthful offender status to a young person who was facing a first-degree robbery charge in which a firearm was used.

Eddie Richmond with his family. Photo courtesy of Wisteria Richmond.

Once in prison, Richmond called his mother often and it was clear to her that he was struggling. “He was worried about coming home and being judged. He said, ‘Mom y’all don’t even know what we go through down here’,” she said.

In phone conversations from prison before he died, Richmond told his mother that once he got out he wanted to travel with his parents. He wanted to go to New Orleans with them, get a job and save up to move away and start over somewhere new. “He had things he wanted to do. He had dreams.”

In many of those phone calls from prison, her son expressed concern that once he got out he wouldn’t be able to shake the stigma of his past. “I tried to instill in him that people make mistakes. You learn from them,” his mother said. His death at a young age in an Alabama prison put an end to that chance.

Wisteria Richmond buried her son on Dec. 29 at Evergreen Cemetery in Opelika. When his birthday comes around on May 20 the family plans to gather together and celebrate his life. “Even though he won’t be here for it,” she said.

A Glimmer of Hope

News of the decrease in reporting on deaths at ADOC has raised concerns among elected officials, including lawmakers from both sides of the aisle and judges.

“Considering how bad things are going in ADOC, now is certainly not the time to be less transparent,” Rep. Chris England, D-Tuscaloosa, said in a Tweet this week. “If ADOC insists on doing the bare minimum here, then maybe we need to change the law to force them to do better. Fortunately, Session starts in March.”

Rep. Matt Simpson, a Republican and former prosecutor from Baldwin County, who has called out ADOC mismanagement in the past, responded: “He’s not wrong.”

Rep. Matt Simpson, a Republican and former prosecutor from Baldwin County, who has called out ADOC mismanagement in the past, responded: “He’s not wrong.”

To put Alabama’s staggering number of prison deaths into perspective, officials with the Vermont Office of the Defender General and the Vermont Department of Corrections in December formed a task force to investigate prison deaths there after an eighth incarcerated person died in Vermont prisons for the entire calendar year.

Vermont’s Defender General Matthew Valerio told a local newspaper that the group will also look into changing release dates for those who have served good time “are not a threat to themselves or society, and are looking for better release dates based on age, health issues and COVID numbers.”

A death sentence for a probation revocation

Another recent death involved an Etowah County man originally convicted of drug charges – distribution of salvia – and sentenced to probation, only to have his probation revoked.

Marc Snow died on November 25, 2022 at Ventress Correctional Facility. He was 25 years old. Photo courtesy of Snow’s family.

Marc Snow died in the health care unit at Ventress Correctional Facility just a few short months later, on Nov. 29. He was 25.

The warden told the family that Snow had just smoked a cigarette and was seen visibly sick in his bed. Snow had a history of using synthetic marijuana, a mix of spices and herbs sprayed with a synthetic compound, and salvia, a plant with psychoactive properties, court records show. The exact cause of Snow’s death awaits a full autopsy and toxicology results.

Snow graduated from a rehabilitation program in Birmingham in February 2021, court records show. Soon after, he was reunited with his young son because he was doing so well, said Tera Cothran, who has had legal custody of Snow’s son since the boy was 18 months old. Cothran’s niece, the boy’s mother, has also struggled with drug addiction, Cothran told Appleseed. “We told my nephew at the beginning of the summer that Marc was his biological dad, and he got an opportunity to spend some time with Marc over the summer,” Cothran said.

Later this summer, Snow’s probation officer received a tip that Snow was selling drugs, and evidence surfaced that he was associating with a woman who had admitted to the officer that she was selling drugs, a woman whom the officer told Snow to stay away from, according to court records. The officer filed for a probation revocation. An Etowah County Circuit judge in September ordered Snow to serve three years in prison, court records show. “That bought him three years at Ventress prison, and a death sentence,” Cothran said.

Snow was not known to use any drugs other than synthetic marijuana and salvia, and court records don’t show he was ever charged with, or tested positive for, any other drugs. “This five-year-old boy’s father was essentially stolen from him, and somebody should answer for that,” Cothran said. “I took this kid to a funeral and he’s barely tall enough to see in the casket.”

Already, a violent start to 2023

A slew of stabbings at St. Clair Correctional Facility over two days at the start of 2023 left numerous men with injuries, a violent start to the new year in Alabama’s deadly prisons.

Appleseed received tips that several men had been stabbed, and the Alabama Department of Corrections confirmed that Bienemy Luther on Jan. 2 was attacked by another incarcerated man at St. Clair prison, and was taken to a local hospital for treatment.

The following day at St. Clair, three men – Martin Adams, Montrell Towns and Ladarius Lucas – were involved in a fight with weapons, ADOC confirmed. Adams was treated for his injuries at the prison, and Lucas was taken to a local hospital for treatment.

That same day Shedrick Williams III was assaulted with a weapon by more than one other incarcerated man, ADOC confirmed. He was treated at the prison for his injuries.

Of the men injured this week, three are serving 20-year sentences and one is serving a 25-year sentence. All are to be released from prison and return to their communities in the future, if they survive Alabama’s deadly prisons.

There were 12 preventable deaths at St. Clair prison in 2022, according to investigative journalist Beth Shelburne’s tracking, which defines such deaths as drug-related, deaths caused by assaults and suicides.

Four days into the new year, the first homicide of 2023 at ADOC occurred. “Ariene Kimbrough, 35, was killed in his cell at Limestone prison. ADOC confirmed the murder but provided no details. Sources say prison staff placed Kimbrough & another man in a segregation cell designed for one person,” Shelburne shared on Twitter.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!