By Leah Nelson, Appleseed Research Director | Leah.Nelson@alabamaappleseed.org

PICKENS COUNTY — Sean and Eboni Worsley’s nightmare began with music a police officer found too loud for his liking.

It was August 2016, and the Worsleys were on their way east, heading from a visit with Eboni’s folks in Mississippi to surprise Sean’s family in North Carolina. Sean’s grandmother had been displaced by a hurricane and he was hoping to help rebuild her house. The couple had some venison in the trunk of their car, a gift from Eboni’s dad, a hunter, that they planned to share with Sean’s family.

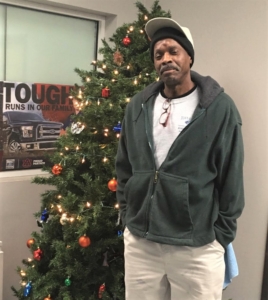

Army veteran Sean Worsley earned a Purple Heart in Iraq

Sean, now 33, is a disabled veteran with a traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) from his deployment in Iraq. He uses medical marijuana to calm his nightmares and soothe his back pain. His medical marijuana was in the back seat. He got the prescription in Arizona, where medical marijuana has been legal since 2011.

Sean was walking into the gas station when Officer Carl Abramo of the Gordo, Ala. police department approached the car. He told the Worsleys their music was too loud. He asked to search the vehicle.

The Worsleys assented. Sean’s marijuana was legally prescribed. They thought they had nothing to hide.

They were wrong. And now Sean has been sentenced to five years in Alabama’s violent, drug-filled, corrupt prison system because of it.

Playing Air Guitar while Black

On August 15, 2016, at 11:08 PM, Officer Carl Abramo was stationed across from the Jet Pep on Highway 82, a major east-west thoroughfare that runs from New Mexico to Georgia. According to an arrest report filed five days after the incident, he heard loud music coming from a vehicle and “observed a Black male get out of the passenger side vehicle. They were pulled up at a pump and the Black male began playing air guitar, dancing, and shaking his head. He was laughing and joking around and looking at the driver while doing all this.”

The couple was Sean and Eboni Worsley, who had stopped a few miles from the Pickens County border to refuel their car. Abramo told them their music was so loud it violated the town’s noise ordinance. They turned it down. According to the arrest report, he smelled marijuana and asked the couple about it. Sean told him he was a disabled veteran and tried to give him his medical marijuana card.

“I explained to him that Alabama did not have medical marijuana. I then placed the suspect in hand cuffs,” the report reads.

Abramo called for backup and three more officers arrived. Eboni explained that they were unaware that medical marijuana was prohibited in Alabama. According to the arrest report, she told Abramo the marijuana was in the back seat.

Abramo searched the car. He found the marijuana and the rolling papers and pipe Sean used to smoke it, along with a six-pack of beer, a bottle of vodka, and some pain pills Eboni had a prescription for. He arrested them for all of it. Pickens is one of Alabama’s 23 partially dry counties, so it is technically illegal to possess most alcohol there — though in practice, the rule is only enforced against violators who are profiting from its sale. He arrested them for that, and for violating the noise ordinance and for illegal possession of marijuana and paraphernalia. Eboni’s pills weren’t in the original bottle, which Abramo claimed constituted a felony. He put the handcuffs on her himself.

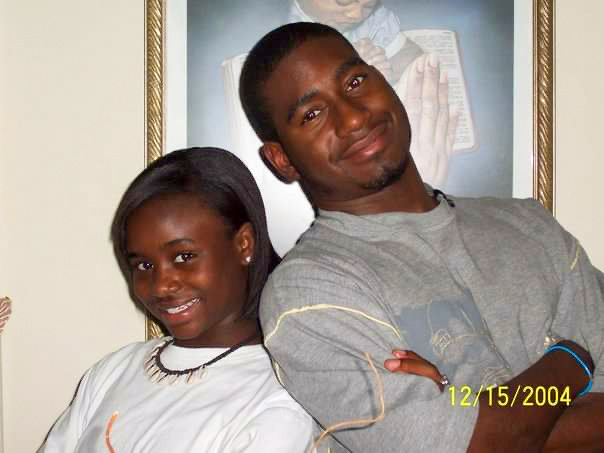

Sean Worsley, and his wife Eboni, in happier days

In 2016, the year the Worsleys were arrested, Black people were more than four times as likely as white people to be arrested for marijuana in Alabama.

The Worsleys spent six days in jail. Their lives would never be the same.

Marijuana is a Schedule One Controlled Substance, meaning that the federal government views it as illegal in all instances. Alabama hews to much the same line: except for extremely narrow exemptions involving CBD, possession of any amount can be a felony. First-time possession is charged as a misdemeanor if the arresting officer thinks it was for personal use; all subsequent instances of possession are felonies. If the arresting officer believes the marijuana is for “other than personal use,” then possession of any amount can be charged as a felony even if it’s an individual’s first time being arrested for possession.

That’s what happened to the Worsleys. Even though Sean’s marijuana was legally obtained via a prescription and packaged in a prescription bottle, Abramo booked him in for possession for other than personal use, a Class C felony. Eboni received the same charge, though it was later dropped.

Abramo, who no longer works for the Gordo Police Department and could not be reached for comment, takes a dim view of those he deems to be criminals. His Facebook page is a mishmash of pro-law enforcement videos and memes that demean Muslims, Mexicans, and Democrats. Nearly all the pro-law enforcement posts feature Black people taking up for the police, a common tactic among conservatives seeking to demonstrate that they are not racist. Many of the rest of his Facebook posts promote racist birther conspiracy theories about President Barack Obama and villainize non-white people and ethnic or religious minorities. One meme, shared in July 2019, states, “Homeless Veterans Should Be Taken Care Of BEFORE Muslim ‘Refugees.’”

“We watched people die. We watched helicopters shoot people down.”

Things would have gone differently if the Worsleys had been traveling through most other states. Recreational use of marijuana is legal in 14 states; medical marijuana is legal in 33. It is commonly used by veterans and others to manage the symptoms of a wide range of ailments, including PTSD and pain. Sean suffered from both as a result of his military service, for which he was awarded a Purple Heart.

In fact, when Sean was 28, the VA determined that he was “totally and permanently disabled due solely to [his] service-connected disabilities,” according to a February 2015 benefits summary letter included in his Veteran’s Health Administration (VHA) records. He suffered from a traumatic brain injury that seriously impaired his short-term memory, as well as PTSD, depression, nightmares, and back and shoulder pain. In 2015, Sean’s impulsivity, cognitive difficulties, sleep disturbances and depression were so debilitating that the VHA determined he required a caregiver. Eboni, then 30, took on that role. Sean’s “dependence level” was high, requiring “maximal assistance” with planning and organizing, safety risks, sleep regulation, and recent memory, and “total assistance” with self-regulation. He responded poorly to the various antidepressants, antipsychotics, and pain medications doctors prescribed.

At times, that meant Eboni couldn’t work, leaving the couple dependent on Sean’s check from the VA. When he could, he supplemented that with part-time work as a roofer and gigs as a recording engineer. Eboni went with him to doctor’s appointments. She helped him keep track of his schoolwork when he sought a business degree to transform his freelance work as a recording engineer into a business.

The VA does not prescribe or fill prescriptions for medical marijuana, nor may VA clinicians recommend its use. However, in light of marijuana’s efficacy in treating ailments common among veterans such as pain and PTSD, the VA is tolerant of veterans who use legally prescribed marijuana. In its official policy document regarding medical marijuana, the VA encourages clinicians and pharmacists to “discuss marijuana use with any Veterans requesting information about marijuana.” A social worker at the VA in Arizona where Sean received care said medical marijuana use is common among her clients and that she has seen how helpful it can be for people suffering PTSD.

Ellis English was Sean’s first-line supervisor while they were deployed together in Iraq in 2006-07. Like Sean, he suffers from PTSD as a result of his deployment. Unlike Sean, he has been unable to use medical marijuana.

English retired from the Army in 2018. He now lives in Honolulu, where medical marijuana has been legal for two decades. He reports that most of his fellow Army veterans there treat their symptoms with medical marijuana. English wishes he could do the same. But because he works for the federal government, he cannot use marijuana without risking his job.

He tried it once anyway when he was overwhelmed by a PTSD flare-up following his retirement. “It was really good. For once I felt relaxed. I didn’t have any pain. No headaches,” he said. “I felt almost normal.”

English remembers what Sean was like before the traumatic brain injury and the PTSD. He also remembers the incidents that caused them. Sean was English’s driver in Iraq, taking him and other troops on dangerous missions to look for and dismantle improvised explosive devices, or IEDs. Often, those devices exploded while the troops were there.

It was dangerous, terrifying work. “We were constantly going. We watched people die. We watched helicopters shoot people down. Had to go pick up the bodies,” English said.

English was with Sean when he received the traumatic brain injury that led to Sean being awarded a Purple Heart. Sean was knocked unconscious and had to be pulled out of the driver’s seat. One soldier lost his hearing on the mission.

Sean changed after that, English said. The young soldier who used to work hard and get things done quickly became unreliable. He zoned out in the middle of work. He stopped taking care of himself. His personal hygiene declined.

Sean changed after that, English said. The young soldier who used to work hard and get things done quickly became unreliable. He zoned out in the middle of work. He stopped taking care of himself. His personal hygiene declined.

One night, he showed up in English’s room weeping and clutching his rifle. English was afraid he was going to kill himself and referred him to mental health. He no longer felt safe having Sean drive him.

“I got him into mental health, he was off the mission for a while,” English said. “Finally, he came back but he wasn’t the same.”

Altogether, Sean spent five years in the military. His deployment to Iraq spanned 14 months, and he was honorably discharged September 22, 2008. Even after his injuries, he served in the Army Reserve until late 2010.

Neither his service, nor his Purple Heart, nor his prescription mattered in Pickens County, Alabama.

What happened next

After six days in jail, the Worsleys were released on bond. It wasn’t cheap: On top of fees to the bail bondsman, they had to pay $400 to get their car out of impound. The meat in the trunk had gone bad after six days locked in a car in Alabama’s brutal summer heat, so the car needed to be professionally cleaned. But at least they were free.

That freedom was short-lived. For a state so eager to honor veterans, Alabama’s justice system produces some confounding results. This system’s determination to punish Sean set off a spiral of job loss, homelessness, additional criminal charges, and eventually incarceration in the country’s most violent prison system — all for a substance that’s legal in states where half of Americans live.

But first, Sean and Eboni drove back home to Arizona. They found the charges made it difficult for them to maintain housing and stability, so they moved to Nevada, where they acquired a home and lived peacefully while their case progressed.

Almost a year later, the bail bondsman called. He told the Worsleys that the judge was revoking bonds on all the cases he managed. He said they had to rush back or he would lose the money he had put up for their bond and they would be charged with failing to appear in court.

They felt the bondsman had been kind to them when they were in Pickens County, so they borrowed money to make the trip and hit the road. They were due in court the next day.

When they got to court, the Worsleys were taken to separate rooms. Eboni was horrified. She explained that Sean was disabled with serious cognitive issues, that he had PTSD, that he needed a guardian to help him understand the process and ensure he made an informed decision. If a legal guardian couldn’t be appointed, she offered to serve as his advocate in court as she served as his caregiver at home.

“They said no, and they literally locked me in a room separate from him. And his conversation with me is that they told him that if he didn’t sign the plea agreement that we would have to stay incarcerated until December and that they would charge me with the same charges as they charged him,” Eboni said. “He said because of that, he just signed it.”

Sean’s plea agreement included 60 months of probation, plus drug treatment and thousands of dollars in fines, fees, and court costs. Because the Worsleys had lived in Arizona at the time of their arrest, his probation was transferred to Arizona, instead of Nevada, where they lived. Transferring it again would mean another lengthy delay and more jail time while the paperwork was sorted out, they were told.

Sean could not bear to stay. The Worsleys got a two-week pass from the probation officer in Alabama, drove home, broke their lease, and packed their things. When they arrived in Arizona, the only housing they could find on short notice was a costly month-to-month rental. Their funds were depleted, but at least they had a place to stay.

Sean could not bear to stay. The Worsleys got a two-week pass from the probation officer in Alabama, drove home, broke their lease, and packed their things. When they arrived in Arizona, the only housing they could find on short notice was a costly month-to-month rental. Their funds were depleted, but at least they had a place to stay.

The Worsleys were ready to start rebuilding their lives. But when they checked in with the Arizona probation officer, she told them that their month-to-month rental did not constitute a permanent address. She would not approve it for purposes of supervision and told them to contact probation in Alabama. They did, and the Alabama probation officer told them they would have to return to Pickens County to sign paperwork to redo the transfer. They didn’t have the money to do that, so they asked their Alabama lawyer if it could be done by proxy and proceeded with attempting to comply with the other terms of Sean’s probation.

Among those was drug treatment. Had he been an Alabama resident, Sean would have participated in mandatory programming through Alabama’s Court Referral, one of several diversion programs operating across the state. The terms of his probation required him to seek similar services where he lived, so in February 2018, Sean went to the VA to take an assessment for placement in drug treatment.

The VA rejected him. A letter from VA Mental Health Integrated Specialty Services reads in part, “Mr. Worsley reports smoking Cannabis for medical purposes and has legal documentation to support his use and therefore does not meet criteria for a substance use disorder or meet need for substance abuse treatment.”

The Worsleys maintained contact with their Alabama lawyer and probation officer as best they could, but things were difficult. Eboni, a certified nursing assistant who works with traumatized children, had a job offer rescinded due to the felony charge in Alabama. She also lost her clearance to work with sensitive information to which she needed access to do her job. For a while, the Worsleys slept in their car or lived with family.

In January 2019, they again found themselves homeless. They requested assistance from a program that helps homeless veterans. Just as they completed the six-month program, the VA notified Sean that his benefits would be stopped because Alabama had issued a fugitive warrant for his arrest. Unknown to Sean, he had missed a February court date in Pickens County and the Pickens County Supervision Program had terminated his supervision, citing “failure to attend” and “failure to pay court-ordered moneys.” The case was referred to the district attorney’s office in March 2019.

The Worsleys were in a terrible situation. Eboni needed heart surgery, and Sean had to stop taking on extra gigs so he could help her recover. Rent was expensive, anywhere from $1,200-$1,500 a month, and they had a car loan as well. To cover costs, the couple took out a title loan, but they were unable to keep up with it. They lost Eboni’s truck. They lost their home and again had to move into a temporary rental, paying $400 a week to live in a suburb about an hour from the hospital where Eboni still had frequent appointments.

Sean was able to get his check started up again around August 2019, but the financial hole they were in was so deep that he didn’t have the $250 to renew his medical marijuana card. It expired.

In early 2020, Sean was pulled over on his way to Eboni’s sister’s home, where he was going to help with a minor repair. He had some marijuana with him. The officers who pulled him over noticed he was terrified. They asked him why. According to Eboni, he told them everything: about this PTSD, his traumatic brain injury, the expired card, the outstanding warrant from Alabama. The officers told him not to worry; Alabama would never extradite him over a little marijuana. It would be OK.

But when they called to make sure, Alabama said it wanted to bring Sean back to Pickens County. When the Arizona police told him, he ran. He fell. He was taken to jail, and eventually, he was transported to Pickens County at a cost to the state of Alabama of $4,345. The state moved to make Sean pay that money himself, on top of the $3,833.40 he already owed in fines, fees, and court costs.

“I feel like I’m being thrown away by a country I went and served for.”

Sean has been in the Pickens County jail since early 2020. On April 28, the judge revoked his probation and sentenced him to 60 months in the custody of the Alabama Department of Corrections.

Over the last three years, there have been robust efforts in the Alabama legislature to modify the state’s marijuana laws. A bill legalizing medical marijuana under controlled conditions passed the full Senate this year before the session ended due to Covid-19. A bill reclassifying possession of two ounces or less as a civil offense passed out of the Senate Judiciary Committee in 2019. Reforms that could have created a vastly different outcome for Sean Worsley are on the horizon.

At the same time, lawmakers who support changes to the law undermine their urgency by insisting that marijuana possession does not land people in prison. Sen. Cam Ward, chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, told a reporter in 2018, “The only people in state prisons on possession of any kind of marijuana are those trafficking the truckloads of it.”

Them, and disabled Black veterans playing air guitar at the wrong time while passing through Alabama.

Sean’s mother hired an attorney to appeal the case, and that process has begun. But sometime in the next several weeks, Sean will almost certainly go to prison. His transport there will be delayed due to Covid-19, which has sickened prisoners at several facilities and killed at least five. He’ll be quarantined for a couple of weeks at Draper Correctional Facility, which was condemned as unsafe and unsanitary for occupation, then refurbished for Covid-19 quarantines this year. Assuming he’s well, Sean will then be released to whichever prison has space for him.

Alabama’s entire prison system for men was found by the U.S. Department of Justice to be in violation of the Eighth Amendment prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment. A U.S. District Judge has deemed its mental health services “horrendously inadequate.” It is almost certain Sean’s mental health will decline further in prison. The Alabama Department of Corrections, which has the highest homicide rate in the country, cannot keep him safe.

Eboni in the hospital for heart surgery

He’ll leave behind two children from a prior relationship, ages 12 and 14, who according to Eboni have already struggled with his absence. He’ll leave behind Eboni, who is due to have another major surgery without her husband and best friend by her side.

In a letter to Alabama Appleseed from the Pickens County jail, Sean expressed despair at being away from his children and from Eboni. He feels humiliated at having to call them from jail, crushed that he is, as he put it, “letting them down” over an arrest stemming from efforts he was making to keep himself healthy. “I feel like I’m being thrown away by a country I went and served for,” he wrote. “I feel like I lost parts of me in Iraq, parts of my spirit and soul that I can’t ever get back.”

Ellis English, Sean’s friend and former supervisor — another Black veteran who has himself been pulled over more times than he can count — feels the same way. “You go over there. You come home messed up. Then you still get targeted” by police, English said. “That’s what hurts the most.”