Family members of incarcerated people struggle for answers as violence and death escalate in ADOC prisons

By Eddie Burkhalter, Appleseed Researcher

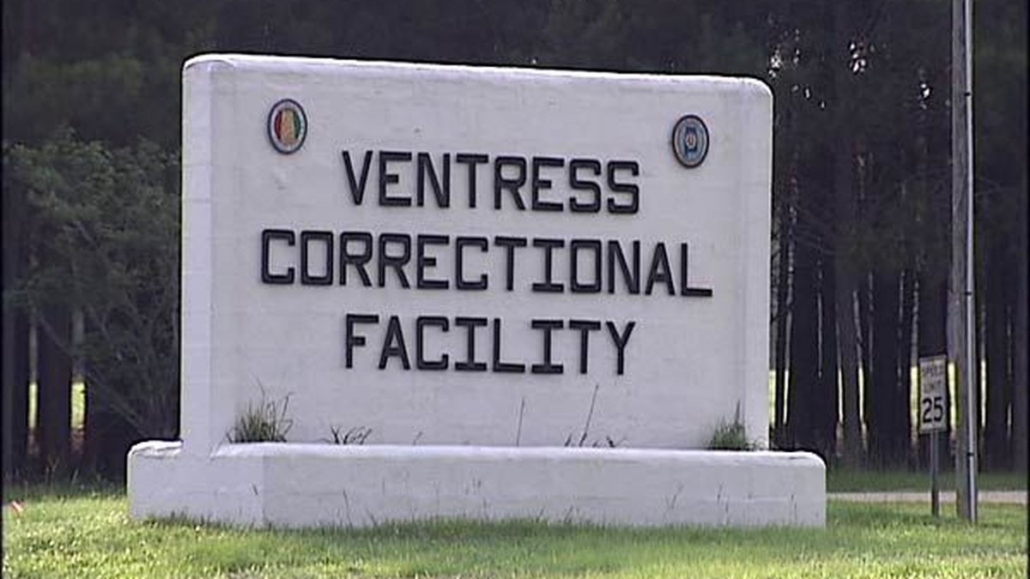

It was five days after Jason Freeman was found lying in the yard at Ventress Correctional Facility in August – two stab wounds piercing his heart – before his mother received a call from a prison official letting her know her son was in the hospital.

It was five days after Jason Freeman was found lying in the yard at Ventress Correctional Facility in August – two stab wounds piercing his heart – before his mother received a call from a prison official letting her know her son was in the hospital.

His open-heart surgery would take place in a matter of hours, a prison captain told her, and there wasn’t enough time for her to make arrangements to get to the Montgomery hospital from her home in Dalton, Georgia.

“Even if I couldn’t have visited him while he was in the hospital, I’d have been there,” Freeman’s mother, Teresa Self said. Lack of information from the Alabama Department of Corrections about loved ones injured or killed in Alabama prisons is common. That same lack of transparency around violence is underscored in the U.S. Department of Justice litigation against the state and the Alabama Department of Corrections.

The 2020 lawsuit, which documents unconstitutional treatment of men in Alabama prisons, is ongoing, yet the death toll in those prisons continues to rise. Families of incarcerated Alabamians face constant worry over their loved ones’ safety and are rarely provided sufficient or accurate information from prison officials.

“He could have died. I would have been there,” Self said of the lack of knowledge that her son had received life-threatening wounds until hours before the surgery.

Self said she got a call from a captain at the prison on Aug. 18 telling her about the pending surgery, but providing no explanation how her son suffered life-threatening injuries while incarcerated for a minor felony.

An Alabama Department of Corrections spokeswoman in a statement said Freeman, who is serving a four-year sentence for drug possession, was found injured in the prison yard on Aug. 13 and was taken by helicopter to a Montgomery hospital.

Self said she tried unsuccessfully for five days to reach the prison’s warden by phone to learn what happened to her son. She didn’t learn he’d been stabbed until a doctor from the hospital called the day of the surgery. She worries for his safety now that he’s back at Ventress. When she finally was able to speak to the warden on August 24, he only told her several other incarcerated men were involved in her son’s attack.

Freeman has since returned to Ventress prison and placed in the prison’s health care unit. “I just hope he gets the right care,” his mother said. “I need to get him moved because if he goes back there they’ll kill him, because they almost did.”

Self is one of many family members who struggle to get the most basic answers from ADOC at a time of near daily reports of homicides, suicides, and drug overdoses within the state’s chaotic prisons and frequent lockdowns due to insufficient staffing. Investigative journalist Beth Shelburne, who tracks ADOC deaths, has documented 55 deaths, likely due to violence, drugs, or suicide thus far in 2022. Last year, there were 42 such deaths.

The family of a man serving at Limestone prison couldn’t get a response from the department about injuries the man sustained in an Aug. 7 attack. They had to learn the extent of his life-threatening injuries, which included a skull fracture, collapsed lung and loss of sight in one eye, by working through family friends, WAAY 31 news station reported.

It wasn’t until after the news station contacted ADOC asking about the attack that the prison’s warden called the family with information, the station reported. WAAY 31 didn’t identify the inmate “due to fears of more targeted violence.”

Carla Underwood Lewis in 2020 found out her 22-year-old son, Marquell Underwood, died at Easterling Correctional Facility from other incarcerated men, and despite attempts to learn how he died from prison officials, she only learned it was a suspected suicide after reading a news article.

Underwood was found unresponsive in his cell on Feb. 23, 2020, but the family received no information from the prison about how he died.

An ADOC spokeswoman told a reporter that it was a suspected suicide, and later said the department “was not made aware that, in this case, the apparent cause of death was not communicated to Marquell Underwood’s mother when the facility’s chaplain contacted her to share this unfortunate news on Sunday evening.”

The U.S. Department of Justice in the federal government’s 2020 lawsuit over Alabama’s prisons for men wrote that the violence and death inside prisons is spurred by overpopulation and a “dangerously low level of security staffing” and ADOC isn’t transparent about that violence and death.

“Defendants, through their acts and omissions, have engaged in a pattern of practice that obscures the level of harm from violence in Alabama’s prisons for men,” the complaint reads.

Meanwhile, ADOC is hemorrhaging security staff. The agency’s most recent quarterly report listed 1879 security officers, less than half of the 3862 required to safely staff the mandatory and essential posts.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!