Ronnie Peoples has paid dearly for a series of robberies decades ago. Now he’s fighting for his life following a cancer diagnosis.

This is the first story in Appleseed’s new series “Cruel and Unusual” focusing on the people harmed by Alabama’s overreliance on excessive sentences, which trap people in deadly, dysfunctional prisons long after they have paid their debt.

By Eddie Burkhalter, Appleseed Researcher

For more than two decades Ronnie Peoples has kept track of the tools used in the trade school at St. Clair Correctional Facility. He’s never been paid for that work, but even today, as cancer spreads across his body, he shows up for work.

The 67-year-old’s workstation is a private respite from the chaos inside the prison. He goes to work to collect his thoughts and ease his mind. It’s hard to find peace in a prison, even harder with cancer.

Mr. Ronnie Peoples

Mr. Peoples has served 32 years of a life without the possibility of parole sentence under the state’s Habitual Felony Offender Act (HFOA). He is among the growing number of very sick and older incarcerated people in Alabama. He was diagnosed with stage 4 prostate cancer in April and while his treatment continues, the disease has spread to a lung and to a rib.

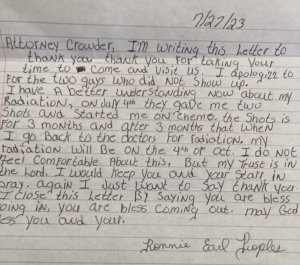

“On July 4th, they gave me two shots and started me on chemo. The shots is for 3 months and after 3 months that’s when I go back to the doctors for radiation. My radiation will be on the 4th of Oct. I do not feel comfortable about this, but my trust is in the Lord,” Mr. Peoples’ wrote in a followup letter after our visit.

Despite an impressive record of rehabilitation and years of positive contributions to living conditions at St. Clair, Mr. Peoples has been condemned to suffer through this disease in the overcrowded, overheated misery of an Alabama prison. More and more Alabamians will face a similar fate, battling life-threatening illnesses in an environment designed for punishment, not healing, as the State’s embrace of life and life without parole sentences plays out to its only possible conclusion.

Mr. Peoples received his life without the possibility of parole sentence after a 1991 robbery of a beverage company conviction in Tuscaloosa County. No one was injured. His sentence was enhanced under the HFOA because of prior robbery convictions more than four decades ago in the 1970s, including in Ohio. Life without parole was the only available sentence at the time, but because of changes to Alabama sentencing laws, Mr. Peoples would have been eligible for a much shorter sentence if current laws applied to his case.

In 2005, Mr. Peoples asked the court to reconsider his sentence. Bradley Black, welding instructor at St. Clair prison’s trade school, in a letter to the judge 18 years ago wrote: “He is an excellent worker and a person whom I can count on and trust. .. I normally do not write letters for the inmates. When Ronnie asked me to write this letter for him, I felt it was the least I could do for someone who has helped me so much and has never asked for anything in return.”

The support letters have stacked up, but still fall on deaf ears. “If not passing out/checking in tools you’ll find him reading the Bible or assisting Mr. Black in what needs to be done in the shop,” a St. Clair trade school security officer wrote to the court in 2005. “Always shows a positive attitude towards inmates/officers.” Another correctional officer wrote to the court in 2005 that Mr. Peoples was a “respectful and trouble free inmate” and that Mr. Peoples played a critical role in helping the officer and another officer quell a gang-related problem at St. Clair prison. “Inmate Peoples appears to be ready to make change in his life,” the officer wrote.

Mr. Peoples’ plea for his sentence to be reconsidered was denied, and 18 years later, he still ensures all the tools in the trade school are accounted for.

Sentences of life without parole essentially make it impossible to pay one’s debt, despite decades of good behavior, accolades, rehabilitation, and toiling away for no pay. Even despite cancer, the punishment is never enough.

A letter from Mr. Peoples to Appleseed’s Executive Director Carla Crowder after their last visit

Mr. Peoples smiled when he talked about his two grown sons, one of whom is a Tuscaloosa County Sheriff’s deputy, but said of his extended family that most of those who were “in my corner have all died.”

Until recently, Peoples said he’s never had problems with anxiety or depression, but news that his cancer had spread to his lungs and ribs hit him hard. He described an incident in June as a “meltdown“ that took two nurses with kind hearts to ease his mind. They encouraged him to speak about his condition with his female friend outside of prison. Peoples said that his friend tends to pepper him with questions about his well-being and expects that he should be able to ask and get answers from those tending to his medical needs. “But it’s not like that in here,” Peoples said. He’s often left wondering what’s next, and can’t get answers from prison medical staff, he said.

He knows that when cancer spreads to bone the timeline for care shrinks, and it’s weighing on him heavily. Few medical staff in the prison are as kind as the two nurses who helped calm him after his “meltdown,” he said. It’s seen as a weakness among prison staff to express concern for incarcerated people, he explained. “If they see you helping others they’ll run you out,” Mr. Peoples said.

He spends time each week in a program called CORE, an acronym for Community, Opportunity, Restoration, and Education, which is a two-year program that teaches incarcerated people how to think differently about themselves and their actions.

“Mr. Peoples has always had a positive attitude towards staff and other members of the CORE community and has been an asset to the program,” Chris Rothoff, CORE program director, said in a statement to Appleseed, adding that Mr. People’s participation in the program “has been outstanding.”

St. Clair Correctional Facility where Mr. Peoples has spent more than two decades

It’s a good program, Peoples explained, and he compared it to a program he and four other incarcerated men started in around 2007 at St. Clair prison called Convicts Against Violence, or CAV. CORE gives students in the program a chance to work on themselves, Peoples said. It’s a chance to better oneself in a prison where drugs and violence are all around you, he explained.

As of May this year there were 7,258 incarcerated individuals aged 50 and older, according to the Alabama Department of Corrections latest monthly report. Over a 50 year period from 1972 to 2022, there was a 3,640% increase in prisoners aged 50 and above. Comparatively, Alabama’s general prison population grew 607% over the same time span. Alabama’s elderly prison population rapidly outpaces Alabama’s general prison population and the state population.

There is no end in sight. The number of people aged 50 and older in Alabama prisons jumped by 17% from May 2020 to May 2023, and the percentage of those aged 60 and older incarcerated in Alabama jumped even higher during those three years, rising by 28 percent.

Medical furlough was a much heralded response when unveiled more than a decade ago. It has accomplished little. Of the 24 medical furlough applications received in 2022, ADOC approved 9, but four applicants died during the review process, according to the department’s report. ADOC approved 10 for medical furlough in 2021.

As prisons fill with more and more older, sicker people, the cost to the state to care for them continues rising. ADOC in 2010 paid $116 million for healthcare “and other professional services.” A decade later, in 2020, that figure rose to $177 million, and jumped again in 2021 to $221 million. ADOC Commissioner John Hamm in February asked legislators for an additional $122 million to the department’s budget, to be spent on infrastructure and health care needs. Now the cost is $1 billion for four years, recently awarded to Tennessee-based YesCare, a for-profit provider.

“There were three stabbings here recently,” Mr. Peoples said. Much of the violence is driven by drug use, especially a synthetic cannabinoids called “Flakka” which can cause a person to act erratically and violently.

Overdoses and overdose deaths are also common at St. Clair prison and throughout Alabama’s prison system, which is embroiled in a lawsuit filed by the U.S. Department of Justice that alleges the state and the Alabama Department of Corrections fail to keep incarcerated men in Alabama free from sexual and physical violence and death.

The 2020 lawsuit followed a Department of Justice 2019 report that details horrific instances of abuse and death in Alabama’s prisons. After those concerns went unaddressed the federal government released a subsequent report in July 2020 that detailed widespread use of excessive force, including deadly force, by corrections officers against incarcerated people.

The 2020 lawsuit followed a Department of Justice 2019 report that details horrific instances of abuse and death in Alabama’s prisons. After those concerns went unaddressed the federal government released a subsequent report in July 2020 that detailed widespread use of excessive force, including deadly force, by corrections officers against incarcerated people.

Alabama overcrowded and understaffed prisons saw a record 270 deaths in 2022, and according to ADOC’s quarterly report, the 80 deaths through March of this year are on pace to set another record high.

At St. Clair prison, which was at 112 percent capacity in May, Mr. Peoples said it’s not uncommon to see incarcerated people living “homeless” after being forced by other incarcerated people to give up assigned beds and sleep instead in the dayroom, or even outside. The drugs and the debt those drugs can generate between the men inside is fueling such aggression, he explained.

And it’s the older men inside who most often become targets for the younger men, Mr. Peoples, explained, men like him who just want to live, in a place where staying alive is a daily struggle with no guarantee.