By Ronald McKeithen, Appleseed guest blogger

Birmingham, AL — Doubts of ever leaving prison had been embedded deep within me. I couldn’t shake them. At least not completely. Even after everything that I’d prayed for and dreamed of for decades had finally been granted: a dedicated legal team and a mountain of supporters that had worked tirelessly to bring my plight to the attention of the world. Yet that fearful, nasty taste of doubt still lingered in the back of my throat. Even after being told that I might leave the following morning.

And what’s more disturbing, I wasn’t ready to leave. There was too much I had to complete, guys to give that last encouraging talk to, and so much to distribute to guys that didn’t have much. I needed more time. At least two more days. Which is the most crazy thing that’s entered my mind since the day I refused the 15 year plea deal the District Attorney offered me in a robbery case. Especially after having served 37 years on a Life Without the Possibility of Parole sentence. I should have been running towards the front entrance as shameless tears fell from my eyes. But I’d been shackled down too long in the insane asylum that is Alabama prison that it shouldn’t surprise anyone if I’d gone a little mad myself.

Regardless of the doubt, hope wouldn’t allow me sleep. I found myself rushing to complete greeting cards I’d started for friends, while contemplating the possibility of actually leaving this place in a matter of hours. Then exhaustion won. I couldn’t stay awake any longer. And if I dreamed of freedom, I wasn’t given a chance to recall it. Because I was awakened from a deep sleep by an officer yelling my name. Telling me to pack my belongings. That I had five minutes. I was confused, disoriented, not fully understanding where I was or what those words actually meant. Wondering why I was hearing applause. I realized that nearly the whole dorm was on their feet, smiling and clapping. Then it hit me. I was going home. If I were alone, I would’ve cried like a baby, but my masculinity wouldn’t allow it.

It was just a few weeks ago that I found myself fighting back tears while sitting in that very spot. After numerous conversations with my lawyers and mailing every document that I possessed that would reveal my activities since my incarceration, and why I’ve spent nearly 40 years of my life in prison, the petition that would be filed to the court had finally arrived. It was the most astounding document I’d ever laid my eyes upon. It may as well have been the Holy Grail. I had made several attempts to the courts pleading my case. Copying other guy’s petitions then rearranging them to fit my case, not fully knowing what I was doing, but knowing I had to do something. Feeling like a mute that didn’t know sign language, straining my throat to be understood, and having to endure the hurt of knowing that they clearly understood yet choose to ignore me. But this petition. It was the first one I’d seen in decades with my name and wasn’t done by me or some jailhouse lawyer. I had to look away several times before reading half of it. And I had to practically run away from it twice to keep my bunkie from seeing tears hanging from my eyelids.

The morning of my release, as the applause died down, I became even more confused. I didn’t have any idea of what to do next. What to pack, what to leave, or where to go. I’ve been ordered to gather all my belongings hundreds of times, to move from one cell, block, dorm or one prison to another prison. But never this. Freedom. And as guys began to surround my bed, each trying to shake my hand or pat my back to congratulate me, I realized that gathering things I should take was useless. That I needed to get out of there. Men began asking me to leave them something, which is expected in such circumstances. So I gave everything away.

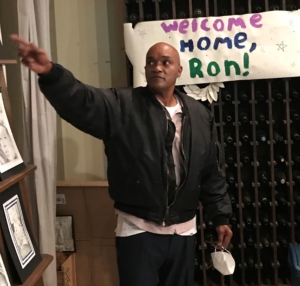

Each time I had previously imagined walking out that gate; I either kissed the ground, stepped into a waiting limousine, or turned around and gave whoever was in the tower a finger from both hands. But the only thing that was on my mind was seeing my lawyer and friends. It hurt not being able to hug any of them. Covid wouldn’t allow it. But the hugs may have been too much to bear, since it’s something I’ve long to do to each of them but never could. I’ve never in my life seen so many people so happy to see me. And it touched me to the core. Their smiles felt like rays from the sun as raindrops fell from a gray sky onto my bald head. I’d given all my caps away. But those raindrops felt so good.

They were all wearing masks, yet the first person I recognized was Beth Shelburne, the woman that started my path to freedom. Through some kind of luck, I was chosen to be interviewed by her for a Fox 6 news story called “Prison Professors” about the UAB Lecture Series that I’d participated in for several years. Retired UAB Professor Connie Kohler was also there. I recognized her from the amount of time I’d spent in our Body & Health class, creating podcasts and newsletters. And there was Pat Vander Meer, the instructor of my book club, who also oversaw the prisons newsletters. I was overjoyed to see her. And there was this tall, elegant lady that I had never seen, yet appeared to be more pleased to see me than the others. She was Carla Crowder of Alabama Appleseed, my attorney, whom I’d only spoken with by phone. God knows how badly I wanted to hug her. There was also Connie’s husband, John. As well as Cedric, who I later learned is the brother of Dena Dickerson, the director of the Offender Alumni Association, who was prepared to help with my re-entry.

I didn’t know what to say. What can you say to people who have saved your life? “Thank you,” or “I owe you one?” None of these responses came close to describing the gratitude that was screaming within. There was so much I needed to say but couldn’t begin to express. To be incarcerated at the age 21, too young and naive to comprehend how willingly I was destroying my life, viewing every arrest as an occupational hazard, whether it be juvenile detention, the city or county jail, or prison. And having to endure decades before the realization that I will die in prison hit home, regardless of how many work reports, classes I complete or certificates I earned, that my life will fade away behind these walls as thousands of others have. And then a miracle happened. Someone noticed me. Then others. And the next thing I knew, people were supporting me. And some of them were standing before me.

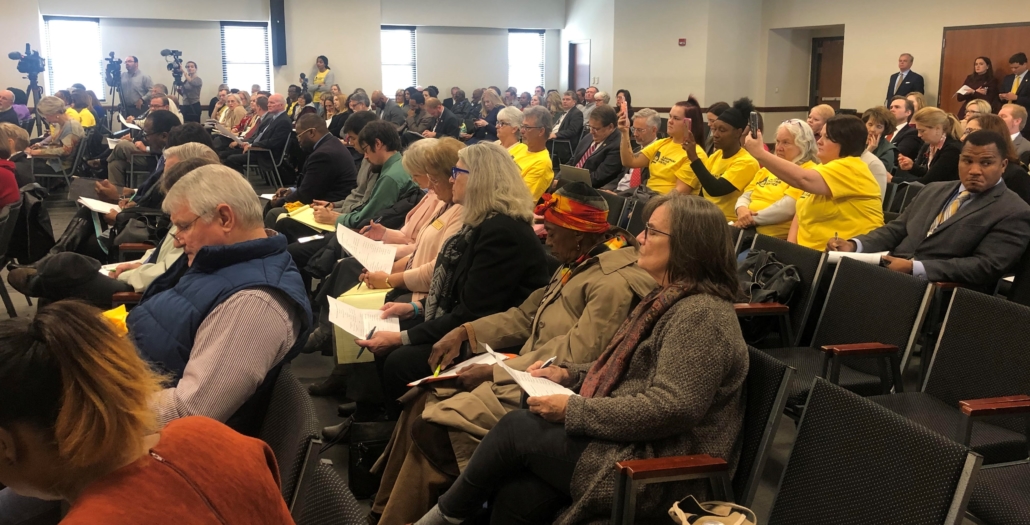

I’d never had a good experience with a District Attorney. The one at my trial said in his closing argument that he wished I was dead, as if I’d done something so despicable, so loathsome, that it required death. Another DA placed in his response to one of my petitions that I had a rape case, which wasn’t true. But this time God blessed me with a fair and just DA to review the post-conviction petition. Jefferson County District Attorney Danny Carr took the time to look at my case and realized that I didn’t deserve to die in prison.

I hadn’t seen the outside of Donaldson Correctional Facility in over 16 years. The sky even looked different. During the drive from the prison, I wanted to ask Cedric to slow down, especially on the curves. I’ve never been on a roller coaster, but this must be how it felt. The constant swerving made me nauseous, and the pictures flashing past my window were making me queasy, but it was the best ride of my life. So much has changed. Unlike the kid that kept repeating ” Are we there yet?” I kept repeating “Where are we?”

I’m still doing it. Birmingham has become a whole new world, and I’m finding everything fascinating and so new. I would notice a squirrel or a small sparrow and become amazed. I’m struggling to stay calm, trying my best to control the googly-eyed expression that just won’t go away. The City of Birmingham may as well have been New York. It was hard to believe that I was gone long enough for all of those buildings to be built. Yet my old neighborhood, Titusville, hadn’t changed, which was very disappointing. The houses that had not rotted away appeared to have nearly 40 years of dust covering them. Yet the Birmingham City Jail looks brand new. I can’t understand how such neglect could occur when so much growth surrounds it.

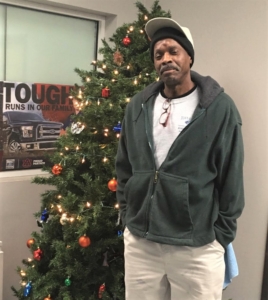

My transition back into society would have been a struggle without my support team; I would have been lost. One of my biggest fans is James Sokol, a retired businessman who believes in me and expects great things from me. The two people that have also played a major role in life since being out is Dena Dickerson, of the Offenders Alumni Association (OAA), and Alex LaGanke, Appleseed’s legal fellow. Dena, a formerly incarcerated person herself, is well aware of what I had endured, and what I would face upon my release – things one can’t learn in a classroom. She and her organization have made my transition beautiful. And Alex has been so instrumental in getting my much-needed documents in order and helping me grasp technological advancements. She’s such a store of knowledge and a delight to be around. I become a student when I’m with either of them.

To say that I’ve settled in and found my balance after six weeks would be a lie, even though I feel that I have. But to be honest, I doubt if I ever will. I spent too much time there. Each day was a constant battle to not give in to that prison mentality and become just another lost soul that fades into nothing. If I hadn’t kept my mind active from classes, I might have lost my mind. I did not have the luxury of being unproductive in prison, nor do I have that luxury out here. I’m experiencing a rebirth, a second chance at life, and every day has been a blessing. I fall asleep in anticipation of the next.