By Eddie Burkhalter, Appleseed Researcher

Stephanie Lewis stood in front of the Alabama State Capitol steps with hundreds of others on Wednesday and pleaded for the system that allowed her husband to die to change.

“It has to change. I know his life was not in vain,” Mrs. Lewis said of her husband’s January death at the Childersburg Work Release facility in Alpine. She’s still seeking answers from the Alabama Department of Corrections, but others inside the facility have said his death involved excessive force by officers.

At least 202 people died inside Alabama prisons in 2025, which was nearly three times the national average. That was a drop from the 277 deaths in Alabama prisons in 2024, following another slight decline from the record high 327 in 2023.

On Ash Wednesday, Alabamians gathered on the Capitol Steps to remember those who died in state prison custody.

More than 1,500 Alabamians have died in state prison custody since Alabama’s elected officials were put on notice by the federal government in 2019 that state prisons were plagued by mismanagement, corruption, understaffing, nonexistent investigations, and violence, including homicides and sexual assaults.

On Wednesday, hundreds of family members harmed by these losses and advocates calling for change met outside the state Capitol to demand action. The Oscar-nominated documentary “The Alabama Solution” tells the plight of men inside the state’s deadly prisons fighting for change from inside. The film’s impact campaign “No More” helped organize Wednesday’s gathering.

“I’m here today to seek justice for my son, who they murdered,” Sandy Ray, from Uniontown, told those gathered on Wednesday. Her son, Steven Davis, was beaten to death by officers in 2019. “And for all of you.”

A woman grieves at a vigil for the 1,500 lives lost in Alabama prisons

The film documented the ADOC’s response to Mr. Davis’s beating death, which involved a $250,000 settlement paid to Ms. Ray, yet the officer involved remains on the state payroll and has been promoted to lieutenant.

Terry Williams spoke to Appleseed by phone prior to Wednesday’s vigil. His 22-year-old son, Daniel Terry Williams, was likely smothered to death in November 2023, according to the state’s chief medical examiner, and there was evidence on his body that corroborate what witnesses have said was his kidnapping and torture over a period of several days inside Staton Correctional Facility. He died the day he was set to be released from prison.

“It hurts a lot, knowing what he had to go through, and I couldn’t help him,” Mr. Williams said.

Despite witnesses who saw Daniel Williams being held against his will in a secure prison staffed with officers, and despite clear medical evidence pointing to homicide and a suspect identified, that suspect has not been charged in Mr. Williams’s death. To date, no one has been criminally charged in connection with his death, which made headlines across the country and altered Alabama lawmakers that nothing they or the Administration had done in the four years since the DOJ report was released had sufficiently addressed deadly prison violence.

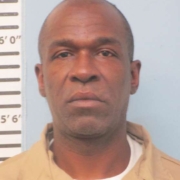

Daniel Terry Williams, 22, was likely smothered to death on November 7, 2022 inside Staton Correctional Facility.

Appleseed’s executive director, Carla Crowder, addressed the Legislature’s Joint Prison Oversight Committee in a December 2023 meeting and presented documentation of ADOC failures that contributed to the death, part of a pattern of failures that has resulted in assaults, rapes, and killings of incarcerated individuals, many of whom were sent to prison for drug treatment and rehabililation. “The 38-year-old suspect in this kidnapping, rape and torture was involved in nine instances of sex assault, rape, and stabbing since 2017 in ADOC while incarcerated. … There is no documentation that he was placed in segregation for any of these assaults. There was no disciplinary action by ADOC,” she said.

Daniel Willaims’ father questions how prison staff would allow such a thing to happen, and said he is seeking justice that so far hasn’t been offered to his family. “Put them in a single cell for the rest of their lives. I want them to sit there and think about what they did,” Mr. Williams said.

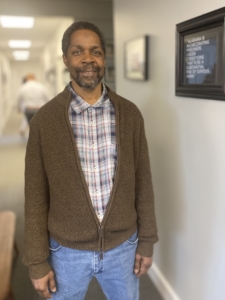

Kelly Ballentine with her grandson, Wayland, drove all the way from Florence to attend the vigil.

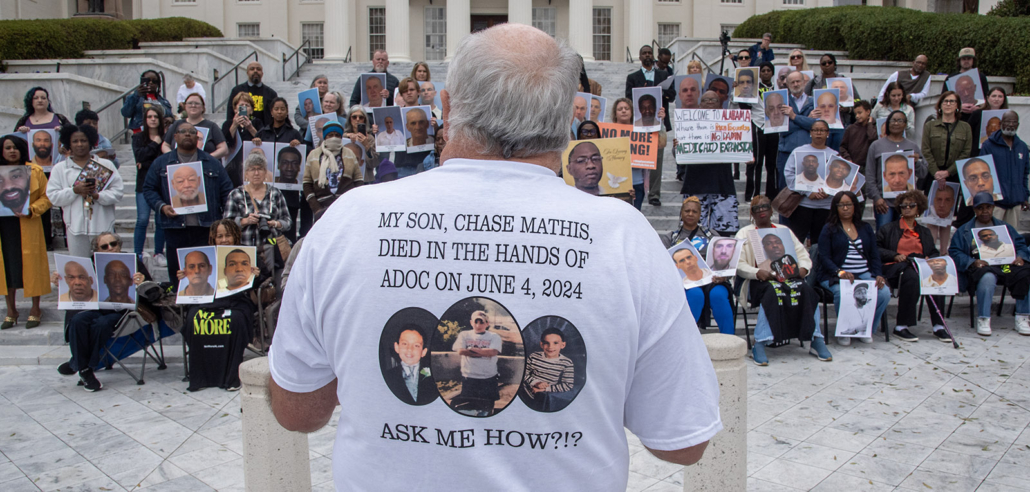

Tim Mathis lost his son to an overdose inside Elmore Correctional Facility on June 4, 2024, minutes after talking to his father by phone. Mr. Mathis, from Dothan, frequently appears before lawmakers demanding accountability and reform.

Overdose deaths, and especially those deaths known or suspected of being caused by fentanyl, have soared in the state’s prisons. The overdose mortality rate in Alabama’s prisons in 2023 of 435 per 100,000 people was 20 times the national rate across state prisons.

What his son’s autopsy report shows is that the state’s medical examiner believes Chase died of accidental “mixed Drug toxicity (fentanyl and fluorofentanyl).” Fluorofentanyl is a synthetic form of fentanyl first produced in the 1960s.

“There’s probably been someone who’s died in the system while we’ve been standing here,” Mr. Mathis said to those assembled outside the Capitol.

Dothan father, Tim Mathis, speaks about his son, Chase Mathis, who entered prison in a wheelchair and never came home. Photo by Bernard Troncale

Asked by Appleseed whether he believes some of Alabama’s decision-makers in Montgomery aren’t aware of the prison crisis, Mr. Mathis explained that he thinks it might be more complicated than that. “Some of them just don’t know. Some of them are just ignorant to it, and then again, maybe some of them don’t want to know,” he said.

That

That