A resource for Alabamians to learn about the human rights crisis in Alabama state prisons, share their knowledge with others, and work for change

Since 2019, when the United States Department of Justice issued a 56-page report calling out unconstitutional violence, death, and corruption across the entire Alabama prison system for men, Alabama Appleseed has been dedicated to guiding communities across Alabama to a better understanding of the human rights crisis in our prisons. We do this by lifting up stories of individuals and families most harmed by this broken system, by researching and documenting evidence-based solutions and alternatives to needless incarceration, and by providing legal services that free older, rehabilitated Alabamians who then share their personal stories of hope and redemption.

A crowded dorm in an Alabama prison

Appleseed shares our work widely across the state, connecting with faith groups, civic organizations, students, elected officials and everyday Alabamians who learn about this crisis and want to get involved. We have developed resources for advocates geared toward educating everyday Alabamians and empowering them to create change.

In the six years since we embarked on these efforts there has been some progress. And for that we are grateful. But given the depth of the dysfunction within state prisons, the need for major systemic reform remains. As laid out below, elected officials vowed to address these brutal conditions back in 2019. Money has poured into the prison system, yet institutional corruption and senseless violence remain rampant. The documentary, The Alabama Solution, painfully exposes these wrenching conditions to a broader audience, demanding a bold response from our state.

Below is a list of research and resources for advocates across Alabama who wish to learn more about this pressing issue, get up to speed on the responses of our elected officials, and use that knowledge to get involved in crucial reform efforts, including holding these leaders accountable.

The Problem: “The combination of ADOC’s overcrowding and understaffing results in prisons that are inadequately supervised, with inappropriate and unsafe housing designations, creating an environment rife with violence, extortion, drugs, and weapons.” United States Department of Justice

The U.S. Department of Justice’s report in 2019 detailed how Alabama’s prisons for men were violating constitutional rights of the incarcerated by failing to protect them from prisoner-on-prisoner violence and sexual abuse. The DOJ’s subsequent follow-up report in 2020 noted systemic problems of unreported or underreported excessive use of force incidents, a failure to properly investigate these abuses and attempts by correctional officers and their supervisors to cover up these violations.

Appleseed’s summary of the DOJ report highlights the inability of the Alabama Department of Corrections to protect incarcerated men from sexual and physical violence and the DOJ’s finding that Alabama prisons had a homicide rate eight times the national average at the time. Appleseed’s summary also makes clear that the DOJ’s report states new prisons alone won’t solve the crisis.

The beating death of Steven Davis in October 2019 at Donaldson prison underscored the ADOC’s inability to control excessive force by correctional officers, even after being on notice of the federal investigation.

Sandy Ray, whose story is featured in “The Alabama Solution,” shows members of the Criminal Justice Study Group photos of her son Steven Davis as a vibrant young man, then after being beaten by prison officers.

The DOJ filed the federal government’s lawsuit against the State of Alabama and the Alabama Department of Corrections in December 2020 and filed an amended complaint in May 2021.

Irrefutable documentation of pervasive violence, illegal drugs, and deaths in Alabama’s largest law enforcement agency

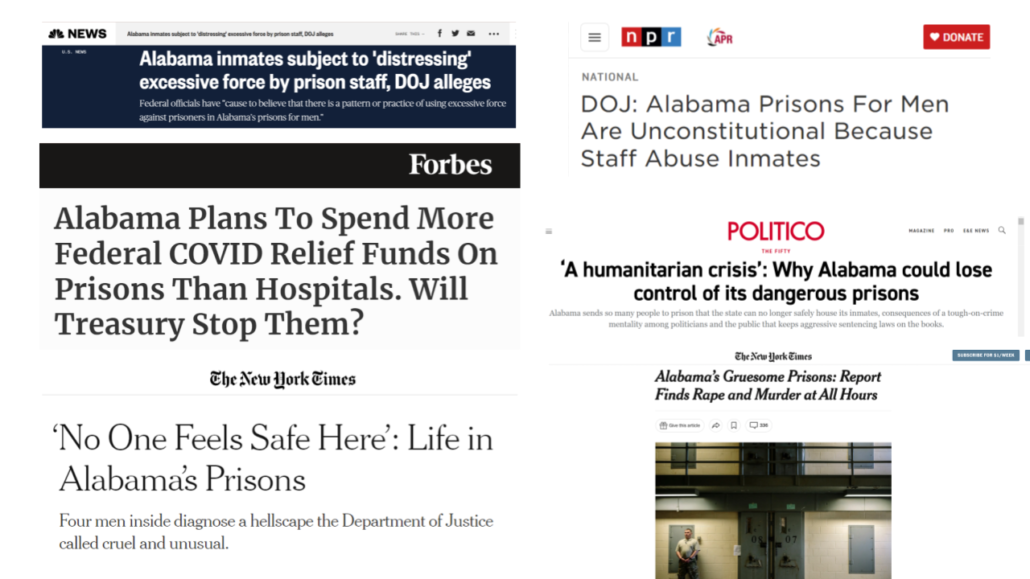

This crisis has resulted in a shameful and embarrassing national spotlight on the state. The New York Times called Alabama’s prisons “gruesome.” In a Fox News report, then-Sen Cam Ward called the findings, “deeply humiliating,” and “disgusting.” Politico called the situation a “humanitarian crisis,” in an article quoting Adam Gelb, president and CEO of the Council on Criminal Justice: “It’s a state that has chased itself around in circles for the past two decades, and there have been some modest improvements, but the system remains terribly overcrowded and filled with people who in many cases should never have come through the front doors.”

St. Clair Correctional Facility

Locally, the Montgomery Advertiser’s reporting includes the story of the beating death of Steven Davis at the hands of correctional officers at Donaldson Correctional Facility. Seven months after the DOJ’s 2019 report the newspaper’s reporting found that “prison officials have withheld food from men, micromanaging minor disciplinary infractions while violence and unexpected deaths continue unabated, including nine which occurred during the reporting of this story in September and October.” The 2019 Advertiser article “American horror story’: The prison voices you don’t hear from have the most to tell us” detailed conversations with incarcerated people who tell of chaos, violence and corruption.

Unfortunately, the situation got worse. Prison Legal News reported more than one death a week in 2022, and bizarre situations such as the videotaped beating of prisoner Jimmy Norman on the rooftop of the Elmore Chapel by a guard.

In-depth reporting by WBHM’s Deliberate Indifference podcast details how Alabama’s prisons became the deadliest in the country, looks closely at understaffing and overcrowding and through the voices of the incarcerated, correctional officers and others, sheds more light on a crisis that was decades in the making.

Appleseed in 2023 began publishing the “Cruel and Unusual” series of reports that focused on the people harmed by Alabama’s overreliance on excessive sentences, which trap people in deadly, dysfunctional prisons long after they have paid their debt, including Ronnie Peoples, a cancer patient who at the time had served more than two decades of a life without the possibility of parole sentence for crimes in which no one was physically harmed. Appleseed’s subsequent research followed Mr. Peoples as he fought to get adequate cancer treatment while still incarcerated.

The prison crisis has captured headlines across the country, portraying Alabama in a problematic light.

Appleseed also spoke to the family of Christopher Mount, who was killed on Mother’s Day 2023 inside a segregation cell with another man in Easterling Correctional Facility. Mr. Mount’s daughter, then-17-year-old MaKayla Mount, in December 2023 told the story of her father’s death and impact on her life to members of the Legislative Joint Prison Oversight Committee. She carried the urn with his ashes into the Statehouse.

MaKayla Mount holds an urn containing her father Christopher Mount’s ashes at the Prison Oversight Committee’s hearing.

Also in the “Cruel and Unusual” series is the plight of Leon Hotchkiss, who is serving a 40-year sentence for growing marijuana. Mr. Hotchkiss, 70, with myriad health problems, has been assigned to the minimum-security Loxley Work Release Center for years and has held multiple jobs in the community. Even so, he was denied parole in February 2023.

Appleseed in April 2023 noted the fourth anniversary of the DOJ’s 2019 report on Alabama’s prisons, which found that between the report’s release and the anniversary date, 698 people died in state prisons. Appleseed’s research also noted that the month that DOJ’s report was published in 2019, Alabama prisons were at 168 percent capacity, and at the time of Appleseed’s publication, prisons remained at 168 percent capacity.

Daniel Terry Williams, 22, was likely smothered to death on November 7, 2022 inside Staton Correctional Facility.

Alabama Daily News reporting on the December 2023 public hearing of the Legislative Joint Prison Oversight Committee includes comments from impacted family members who told of deaths, assaults, torture, extortion of those family members and of the indifference of prison staff. In AL.com’s subsequent reporting on the Committee’s July 2024 meeting the mother of Derrick Martin, killed by another incarcerated man in Elmore Correctional Facility, told members that her son discussed with her the stabbing and beatings he suffered during six years behind bars.

In 2024, Alabama prisons remained unconstitutionally dangerous places, Appleseed found, where more than 1,000 people had died inside Alabama prisons since the DOJ’s 2019 report release. The national spotlight again glared on the state with the kidnapping and torture death of 21-year-old Daniel Williams at Staton prison, days before his scheduled release. An Appleseed investigation found that the suspect in Mr. Williams’ death was involved in nine instances of sex assault, rape, and stabbing since 2017 while incarcerated in ADOC, yet he was never placed in segregation to prevent additional victimization. No criminal charges were ever filed. Numerous deaths are also the result of dangerous drugs brought in by prison staff.

Violence by ADOC officers has remained pervasive. The Alabama Reflector in May 2025 published the first of the four-part series “Blood Money” that details 124 lawsuits that ADOC settled between 2020 and 2024, 94 of which involved complaints of excessive force by officers. The cost of defending those lawsuits pushed ADOC’s legal spending over $57 million since 2020.

The State of Alabama’s Responses

Gov. Kay Ivey in 2019 announced the formation of the Governor’s Study Group on Criminal Justice Policy that was to “receive and analyze accurate data, as well as evidence of best practices, ultimately helping to further address the challenges facing Alabama’s prison system.” While the study group’s recommendations, released in January 2020, did include suggestions on spending and ways to reduce recidivism, the group declined to take up more substantive sentencing reform measures. Former Alabama Supreme Court Justice Champ Lyons, who chaired the Study Group, issued this warning five years ago: “The time for action is now. We dare not abide by a status quo that risks the potential for costly and disruptive intervention by federal authorities.”

The Governor’s Study Group on Criminal Justice Policy. Photo courtesy of the Associated Press.

Ivey in May 2021 signed several criminal justice reform bills into law, but only one bill would have a minimal impact on prison populations by reducing prison sentences by up to one year for incarcerated people who complete academic and vocational programs. Instead of making a serious effort to reduce the prison population, the Governor’s Office forged ahead with a massive, costly prison construction plan, insisting “this Alabama problem has an Alabama solution.”

Alabama’s new 4,000-bed prison is under construction in Elmore County. While the project was initially projected to cost $623 million, the cost ballooned to $1.28 billion. Lawmakers told Alabama Daily News that the state has secured 60% of the cost of a second 4,000-bed prison, to be built in Escambia County. Neither of the new prisons is expected to ease overcrowding, however, as the legislation authorizing prison construction requires the closing of several existing prisons, and acknowledges the intent of the law is to “replace existing prison facility capacity.”

The state is spending billions on incarceration, yet the money hasn’t made a dent in the violence and death inside prisons. An Appleseed analysis found that state prison expenses over a five fiscal-year period, from 2022-2026, will reach $5 billion. That monumental figure includes the annual General Fund allocations to the Alabama Department of Corrections, plus the costs of new prison construction including debt service, but does not include the at least $57 million paid out of the state’s General Liability Trust Fund in recent years on ADOC legal expenses, primarily private contract attorneys to defend officers accused of misconduct and to defend the ADOC in federal class action litigation over unconstitutional prison conditions.

The Alabama Joint Prison Oversight Committee was formed by legislation in 2021 and in meetings held since, those members have heard from directly impacted families members and from ADOC officials. One product of those discussions was the formation of ADOC’s Constituent Services unit, tasked with answering family members’ questions and concerns about the health and safety of incarcerated loved ones. Oversight Committee Chair Sen. Clyde Chambliss, R-Prattville, sponsored legislation that allowed ADOC to hire an additional 15 people to staff that unit.

In an effort to increase hiring and bolster retention efforts, Alabama in 2023 increased correctional officer pay, so that officer trainees can earn between $52,000 and $58,000, with a 27% pay hike after 18 months. One year later, ADOC officials told lawmakers that the department wouldn’t meet a judge’s order to hire an additional 2,000 officers by mid-2025. In 2024, ADOC announced a partnership with the Alabama Community College System that would see the system offer a free career prep program for people interested in working for ADOC. Enrollees in the program can earn up to nine tuition-free college credit hours.

Overall, even with the knowledge that the prisons are deadly and unconstitutional, Alabama lawmakers have passed bills that lengthen sentences, reduce parole and good time, and increase the prison population. The Alabama Sentencing Commission released research in September, 2025 showing that prisons “could see inmate populations rise by nearly a third by 2030 due to new punitive laws passed by the Legislature. The Commission, working with Applied Research Services, a research firm that studies criminal justice, estimated the population in custody of the Alabama Department of Corrections could grow from 21,753 to between 24,000 and 28,000 inmates, depending on the number of people that the ADOC admits each month on average.”

Appleseed’s efforts: Justice for people, justice for Alabama

Since 2019, Appleseed has been working with stakeholders across Alabama to raise awareness about this crisis, develop evidence-based solutions, and garner bi-partisan support for meaningful reform. We’ve given dozens of presentations, testified before the Legislature, produced reports and policy briefs, and our team member Ronald McKeithen holds a seat on the Statewide Reentry Commission tasked with reducing recidivism. We will never stop beating the drum that to move beyond this crisis the state must develop alternatives to incarceration so that fewer people will ever enter the prison system, while also identifying (and freeing) older people who have paid their debt, aged out of criminality and whose permanent incarceration wastes resources.

That’s why Appleseed is also committed to direct legal representation and reentry services, focusing on older prisoners serving extreme sentences, who will likely die in prison without legal assistance. Our post-conviction and parole work has freed more than 30 people who have served more than 800 years combined in these prisons, people such as James Jones, 78, who served 43 years before we won his freedom.

James Jones and Appleseed’s reentry team

Among our policy victories:

Grace Period Bill

In 2022, Appleseed advocated for the Grace Period Bill, which passed in its first session. The Grace Period Bill made it so individuals leaving incarceration have about 6 months before they have to begin paying back any of their legal financial obligations. This allows them time to obtain employment and begin getting back on their feet before they’re required to pay money they don’t often have on hand.

Constituent Services Unit Bill

In 2024, Appleseed helped move SB322, a bill that, among other things, created the Constituent Services Unit at the Alabama Department of Corrections. This unit is tasked with responding to the concerns of family members, loved ones, and anyone else who has concern for an incarcerated person. The bill mandated an online form be publicly available on ADOC’s website, which is now up and running, and that there be a phone number associated with the unit. This bill was passed in large part due to the advocacy of families of incarcerated Alabamians.

Second Chance efforts and successful legal work

In 2019, a judge reached out to Appleseed about a case where a man had been sentenced to life without the possibility of parole for crimes with no physical injury to a person. He had served over three decades for a $50 robbery at a Bessemer bakery. Appleseed represented this man, Alvin Kennard, and he was resentenced to time served and released. Since then Appleseed has discovered there are hundreds of older incarcerated people serving life without parole sentences under the state’s Habitual Felony Offender Act for crimes with no physical injury to a person.

In the years since 2019 Appleseed has won the release of 23 people originally sentenced to die in prison, and nearly a dozen more freed through parole. Most are over the age of 60 and all of them served multiple decades in prison. Many of their stories are documented on Appleseed’s Second Chance Alabama website. Men once condemned to die for crimes with no physical injury– often when they were young or dealing with substance use disorders– are now living lives free with their families and friends, working as buffers for Town and Country Ford or drivers for Western Express Trucking, volunteering with church ministries, playing in dominoes tournaments and walking their dogs. We’ve developed a comprehensive reentry program staffed by reentry professionals to ensure they succeed.

A group of Appleseed’s successful second chance clients, all freed from life without parole sentences

While providing the direct legal representation required to continue obtaining freedom for these individuals who remain incarcerated, Appleseed has also worked at the legislative level to create a state-level change that would allow these individuals and their cases to be reviewed systematically by judges across the state. While the Second Chance Bill has yet to pass, the bill made it to the final step in the legislative process two out of three years, and has garnered broad, bipartisan support from former state Supreme Court justices, prison ministries, a former U.S. Congressman, and Gov. Kay Ivey herself.

Real Solutions are within reach, but we must move past slogans and political posturing

Appleseed’s 2020 “In Trouble” report surveyed 1,011 justice- involved Alabamians about their experiences in pre-trial diversion programming and drug court. We found that Alabama’s tangle of overlapping, unaccountable, and expensive diversion programs are not equally available to people who most need them. And structural obstacles force participants to make unconscionable choices in order to succeed, including committing new crimes. Appleseed recommends fully funding diversion programs and alternatives to incarceration, rather than relying on program participants to foot the bills. We assisted the Jefferson County District Attorney’s Office in the development of Reset, a program that does just that.

Alabama’s reliance on life imprisonment for a wide range of offenses has resulted in soaring numbers of older, incarcerated people trapped in prison until death. Appleseed’s 2022 report “Unsustainable” details Alabama’s rapidly-aging prison population and rising cost to the state to care for the more than 7000 incarcerated people over age 50. Appleseed recommends passage of a “second look” bill that would provide a mechanism for judges to review the sentences of people serving life and life without parole under Alabama’s Habitual Felony Offender Act, who have already served decades and have demonstrated rehabilitation. Expanding medical furlough laws to work as intended can also immediately alleviate systemic strain while recognizing the humanity of the individuals in Alabama’s prisons.

In 2025 Appleseed published the “Positive Programs” report that gives examples of real-world prison programs, many led by incarcerated people, in other states that are reducing recidivism and instances of violence and fostering more humane conditions of confinement. Appleseed recommends that Alabama lawmakers, ADOC officials and other stakeholders should reach out to those out-of-state leaders to learn more about these programs, that ADOC should recognize the most successful programs are led by incarcerated people themselves and ADOC should increase its collaborations with universities and other programming partners.

You can learn more about these and other related issues by reading these and other Appleseed’s reports.

What YOU can do

Show up! The Joint Legislative Prison Oversight Committee has scheduled three meetings for 2026:

- January 28

- April 22

- July 22, which will be the annual public hearing during which individual members of the public may address the board.

The presence of everyday Alabamians, families and friends of incarcerated people, faith leaders, and advocates at these meetings has led to real, systemic change and has created a renewed focus on the crisis in Alabama’s prisons. We encourage you to attend! If you can’t, the meeting can be watched live or later on The Alabama Channel. Continued attendance by concerned Alabama’s is critical to ensuring legislators know their constituents are watching. Already, the committee has taken noticed of increased attention from the public. The October committee meeting was packed and a larger room was required to hold everyone. Great job advocates!

Find out who your state legislators are and get to know them! It’s important to not only know who they are, but to build a relationship with them so you can reach out to them proactively, rather than only in a reactionary way. They represent YOU– make sure they hear from you so they can do it well! Find contact information for your state senator here, and your representative here. You do not have to be an expert on criminal justice reform. You can simply share that you are a voter who cares about the rights and treatment of incarcerated people and you want to know what they are doing to make prisons safer beyond just building more of them. You can also contact Appleseed’s Policy Director, Elaine Burdeshaw, for tips on speaking with lawmakers. She can be reached at elaine.burdeshaw@alabamaappleseed.org.

Policy Director Elaine Burdeshaw at the Alabama Statehouse with Appleseed clients

Pay attention to criminal justice legislation during the 2026 Alabama Legislative session, which starts in January. Because 2026 is an election year, lawmakers feel pressure to avoid taking risks. Leaders who support even modest prison reform can be accused of being “soft on crime,” which is unpopular in Alabama and part of what has led to the crisis documented above. While 2026 will be a tough session for creating change through legislation, even tougher than the previous six sessions, where little was accomplished, lawmakers must hear from constituents!. Sign up for Appleseed emails to learn more about the issues, the bills, and how to engage with elected officials during this important session.

Host a presentation at your church, civic group, school, or business– reach out to us and we’d be happy to join you. Appleseed can provide reports and materials to educate you and your colleagues. Also, our formerly incarcerated clients can be part of a presentation to provide vital insight on prison conditions and the urgency of reform.

Spread the word. Tell your friends, neighbors, community members about what you know. Advocacy and change often move at the speed of relationships– the more we all know, the more we can do together! Appleseed’s website contains numerous ways to learn about these issues and get involved. You can also request a presentation by Appleseed. Our policy experts, legal staff, and formerly incarcerated clients speak across the state (and sometimes in other states!) about all aspects of Alabama’s criminal justice system. Email us at admin@alabamaappleseed.org to request a presentation.

Visit the #NoMore Campaign website. The Alabama Solution campaign website contains more data, policy suggestions, and a call to action for all Alabamians to get involved. Visit NoMoreAlabama.com.

Finally, if you have a loved one who is sick or being mistreated in an Alabama prison, you should be able to get information about them. ADOC in 2025 formed the department’s Constituent Services unit staffed with employees at each major prison tasked with providing information to concerned family members and acting upon pleas from those family members and advocates for help when incarcerated people are in danger. That online form can be found here.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!