By Appleseed Executive Director Carla Crowder

As I wrap up a whirlwind first year as executive director of Alabama Appleseed, I could not be more excited about the work we have done and the places we are heading. This has been a banner year for Appleseed. We have confronted laws and policies that harm vulnerable Alabamians, celebrated key victories, and cemented our reputation as a leading advocacy organizations in Alabama. It has been my honor to advance the work of this storied institution, and I wanted to share some highlights with you as 2019 comes to a close.

At the statehouse, we netted three big legislative wins:

- Our investigation, litigation, and advocacy around sheriffs personally pocketing tax dollars meant to fund food for inmates in their custody, including one sheriff who purchased a $740,000 beach house with jail food funds, led to the passage of legislation that ends this Depression-era practice once and for all.

- Our groundbreaking 2018 report on civil asset forfeiture abuses in Alabama, Forfeiting Your Rights, led to legislation that requires law enforcement to track and publicize how much money and property they seize from the people they police. We expect this new, comprehensive, public database to corroborate the widespread abuses we discovered during our investigations, and we will use its findings to lead the charge toward ending civil asset forfeiture altogether.

- We also changed laws related to filing fees for indigent people in civil courts. It used to be that a victim’s lawsuit could be thrown out if they could not pay hundreds of dollars in filing fees quickly enough. Not anymore. This year, we succeeded in changing the law so that all Alabamians have greater access to our civil courts regardless of whether they can afford to pay the filing fees.

Appleseed staff with Brewer Torbert honoree Bryan Stevenson

In 2019, we also continued our service as the preeminent, trusted source for trailblazing public policy research and game-changing reports that document the harms of bad laws in Alabama. We published two major reports in 2019: Broke: How Payday Lenders Crush Alabama Communities, and Hall Monitors with Handcuffs: How Alabama’s Unregulated, Unmonitored School Resource Officer Program Threatens the State’s Most Vulnerable Children. We simultaneously completed intensive, statewide research projects that will underpin forthcoming reports in 2020. These reports are the foundation of our approach to advocacy. Our investigative work quantifies, makes visible, and humanizes the issues; it sparks the data-informed, solution-oriented conversations that lead to new ways forward; it is the resource that we take to legislators and to communities across the state as we make the case for change.

And indeed, an essential part of our mission is ensuring that our research does not just live on a bookshelf. That’s why we have led public events, community forums, town halls, and stakeholder meetings all across Alabama in 2019, from Dothan to Florence, from Huntsville to Mobile, from Tuscaloosa to Phenix City, from Andalusia to Birmingham. You can be sure that in 2020, we will be inviting people into our work in a community near you, if not in your hometown. The issues we tackle are statewide in nature, and we are committed to a statewide strategy to win a better Alabama. We need all of us engaged in this work.

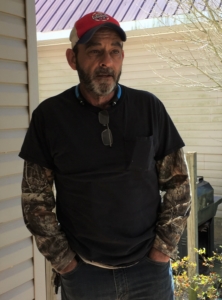

Perhaps our most poignant victory was our representation of Mr. Alvin Kennard, a remarkable gentleman who spent 36 years in an Alabama prison following a $50 robbery in 1983. Mr. Kennard is one of hundreds of people who were sentenced to life without parole under Alabama’s harsh “Three Strikes” law. Our success in charting a path out of prison for Mr. Kennard — someone who poses no threat to society — has raised hopes that others may soon return to their families.

We are exploring options to scale this work up to help other people sentenced to die in prison for offenses with no serious injury. It is just one part of our work to confront Alabama’s dire prison crisis, which was documented this April by a Department of Justice report that declared Alabama’s prison system unconstitutional. Today, only a few months since his release, Mr. Kennard is living with family and gainfully employed at a car dealership.

We are proud of these accomplishments — all the more so because we have achieved them with a small team on a small budget. Our team of four dedicated and inventive staff members at Alabama Appleseed stretches every dollar to tackle the toughest challenges in this state. We have cultivated a statewide network of supporters, allies, and advocates that we bring to bear at the legislature, and our work has garnered national attention and acclaim from voices as varied as The New York Times, NPR, FOX News, The Washington Post, Reason Magazine, the Brookings Institution, and the Aspen Institute.

Alabama needs Appleseed more than ever, and we are ready. As we reflect on this year of hard-earned victories, I thank you for your financial support — and I ask that you stay with us in the coming year. Justice and equity for all Alabamians cannot be won without you.

I hope that you have a happy holiday season, and that you feel proud of the work you have made possible this year. At Appleseed, we believe in a better Alabama, and we’re fighting for it. We will see you in the new year.

Appleseed Research Director Leah Nelson listens to expert panelists at our Fines and Fees event with the Aspen Institute.