By Akiesha Anderson, Appleseed Policy Director

On March 30th, Alabama Appleseed sent a letter to Dr. Scott Harris—Director of the Alabama Department of Public Health (ADPH), and Brian Hastings—Director of the Alabama Department of Emergency Management (ADEM), urging their agencies to share with Appleseed and the general public their plans to ensure that COVID-19 testing sites would be set up in every county throughout the Black Belt.

What factors motivated the decision to send this letter?

The answer for this is simple, I care about the plights and difficulties that affect us, as a community and society.

It is very well understood that we are all navigating the struggles associated with combating COVID-19 as a society. In the recent weeks, there have been national, state, and local conversations about the disproportionate impact that COVID-19 has had on Black communities with the understanding that this is tied into inequality in our health care system. Although these conversations about how racism and bias negatively impact how Black people in America receive access to healthcare are not new, they remain essential. It is also essential that as we have these conversations, we delve exploring the intersectionality of race, poverty, gender, and geography.

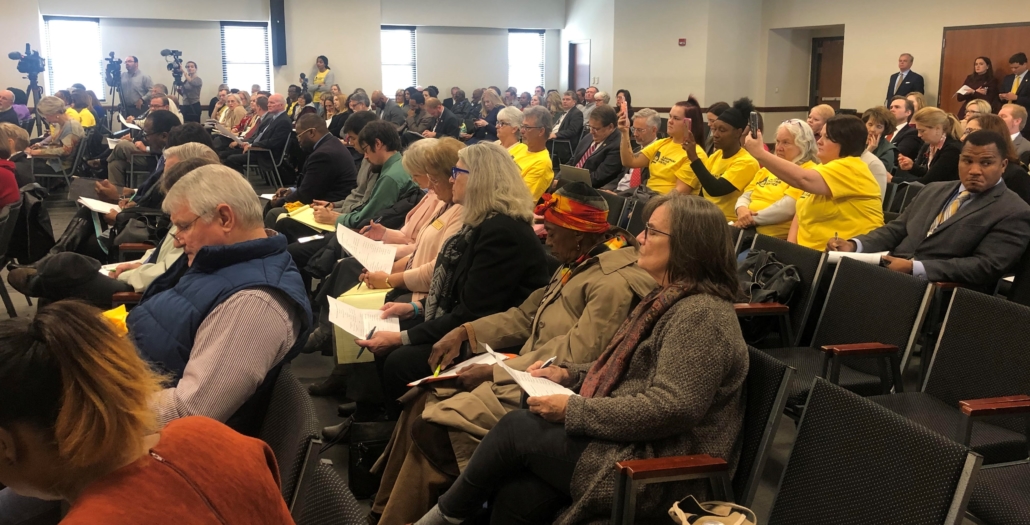

A farmer hauls hay in Lowndes County, one of the poorest counties in the nation. Photo Bernard Troncale

At the time the letter was sent, there were a total of 831 confirmed COVID-19 cases throughout the state, and the first case of COVID-19 had been confirmed in Alabama only 10 days prior. While it was admirable to see that within 10 days the state was able to test nearly 1000 Alabamians, it was concerning to know that although 13% of all tests had resulted in a positive case, less than 1% of those positive cases were found in the Black Belt.

According to 2019 Census data, residents of the Black Belt counties make up 11% of Alabama’s population. Census data also reveals that the Black Belt has a higher percentage of both Black and poor residents that the statewide average. Given reports of testing shortages generally, the limited information gleaned from ADPH data, historical context, and the demographics of the Black Belt, it seemed unlikely at the time, that the state was disseminating the same resources to the Black Belt as they were other communities.

What did we learn in the weeks immediately after sending the letter?

Within just a few hours of receiving our letter, Director Hastings shared that it was his belief that plans were in place to expand testing throughout the Black Belt. This sentiment was repeated by elected officials and leaders throughout the coming weeks, as I continued to inquire about when testing sites would expand throughout the region. In lieu of permanent testing sites, many Black Belt counties have relied on mobile testing sites in an effort to increase testing. Over the past weeks, several Black Belt counties set-up these mobile sites at the County Health Departments.

In early April, ADPH employees revealed that there was no clear plan with regard to how often any of the mobile sites would return to each county. In Wilcox County, for example, an employee at the County Health Department shared with me that they were unsure whether the mobile testing sites would be returning every week or on a case-by-case basis. However, the employee feared it would be the latter.

In addition to barriers to testing created by such infrequencies, testing within these counties was seemingly somewhat inaccessible to Black Belt residents for several other reasons. For example, due to the limited amount of tests distributed throughout the state, health departments within the Black Belt indicated that they were using specific and narrow criteria to pre-screen patients beforehand to determine who could receive testing. Specifically, the county health departments reportedly were only testing people that BOTH (a) had a doctor’s referral and (b) met the following criteria: (1) were symptomatic with a fever, cough, shortness of breath AND were either (1) 65 or older, (2) a health care worker, or (3) someone with an underlying health condition that makes them immunocompromised/at higher risk.

These criteria were troubling for numerous reasons. While this criteria might have seemed normal and like an appropriate way to determine how to prioritize the allocation of limited resources/tests, such criteria essentially meant that many Black Belt residents would be considered ineligible for testing at the State Department of Health sites. Worth noting first, this criteria was stricter than the criteria outlined on the ADPH website. That suggests that as a matter of unofficial policy implementation, Black Belt residents might have had a harder time accessing tests than members of other communities throughout the state. Secondly, as previously discussed, there are a number of characteristics unique to rural, Black Belt, and poor communities that likely made these criteria more harmful than helpful. For example, considering the historic disinvestment in rural and Black Belt counties it is possible that Black Belt residents are less likely to have access to a doctor that is able to give them a referral. Also, for those who do have access to a doctor, research has long shown how racism and bias plays out in the healthcare system, so minority and poor people are also at the mercy of whether or not a doctor even believes them or finds them credible or worthy enough of receiving an exam. Similarly, due to healthcare shortages and vulnerabilities that have existed long before COVID, it is also likely that members of Black Belt communities may have undiagnosed health conditions that they are unaware of simply because they don’t have the same access to healthcare professionals as members of other communities do.

Has testing in the Black Belt improved in the past month?

Although the Black Belt still lacks permanent testing sites within eight of its ten counties, in the month since Appleseed wrote to Dr. Harris, testing capacity and rates have risen. Within the last two weeks for example, testing of Black Belt residents has nearly doubled—as tests administered to Black Belt residents rose from a total of 4645 on April 21st to a total of 8362 on May 1st. Despite the fact that testing throughout the state of Alabama remains low—less than 2% of the state’s population has been tested— testing amongst Black Belt residents is beginning to reach parity with State-wide rates, have gotten closer to reaching parity with statewide rates. As of May 1st, approximately 1.5% of the Black Belt has been tested for COVID-19. However, as Black Belt testing increases, we are beginning to witness the opposite problem of what was seen weeks ago, when Black Belt residents seemed to be underrepresented when assessing positive test results. In contrast, as testing increases, we are beginning to witness Black Belt residents are becoming overrepresented with regard to positive test results. Although Black Belt residents make up 11% of Alabama’s population, they now make up 16% of the COVID-19 positive test results.

What does this increase in positive COVID-19 cases within the Black Belt reveal?

It is no secret that there have been numerous challenges that the state Department of Health and other state leaders have had to navigate since the first coronavirus case was confirmed in Alabama. However, the recent rate at which new cases have been confirmed within the Black Belt suggests that the previously low number of confirmed cases likely resulted from simply a lack of testing rather than a lack of occurrences. Given this possibility along with the State’s decision to slowly reopen the state by rolling back both social distancing and business restrictions; it is possible that the state may not be able to increase testing in enough time to detect and prevent spread of existing COVID-19 cases in the area.

A 71-year-old farmer in Perry County, Alabama waiting on parts to fix a broke tractor. Photo Bernard Troncale

Something to Ponder

Every policy, action or inaction by a public official or governmental institutions is ultimately a decision that tells us something about what people, communities, and beneficiaries said actors both prioritize and deprioritize. Which communities get allocated resources, how quickly, and how many resources has long been deeply inequitable and oft-times exclusionary process. As leaders continue to make decisions about the allocation of resources during this epidemic, we should be vigilant to fight against the inequities that race, class, and nepotism can create. Because policy makers and public officials routinely sacrifice some people for the perceived “greater good” of others, we must continue to challenge who we allow decisionmakers to deem as “disposable”.

Alabama Appleseed’s mission of justice and equity for all Alabamians compels us to do so. Given what’s at stake with this pandemic, this mission is more urgent that ever.