The former high school football star used marijuana to manage pain from a catastrophic accident. Did Alabama law enforcement charge him as a drug kingpin so the state could keep his car, cash, and other valuables?

By Leah Nelson

Leah.Nelson@alabamaappleseed.org

PHENIX CITY, ALA. – Quandarius Holt must have thought that the worst things that could happen as a result of being struck by an 18-wheeler in 2018 were already behind him. The 23-year-old former high school football star had already lost his left leg above the knee and endured multiple surgeries, resulting from a tractor trailer crashing into him as he helped a motorist move her disabled car off the road.

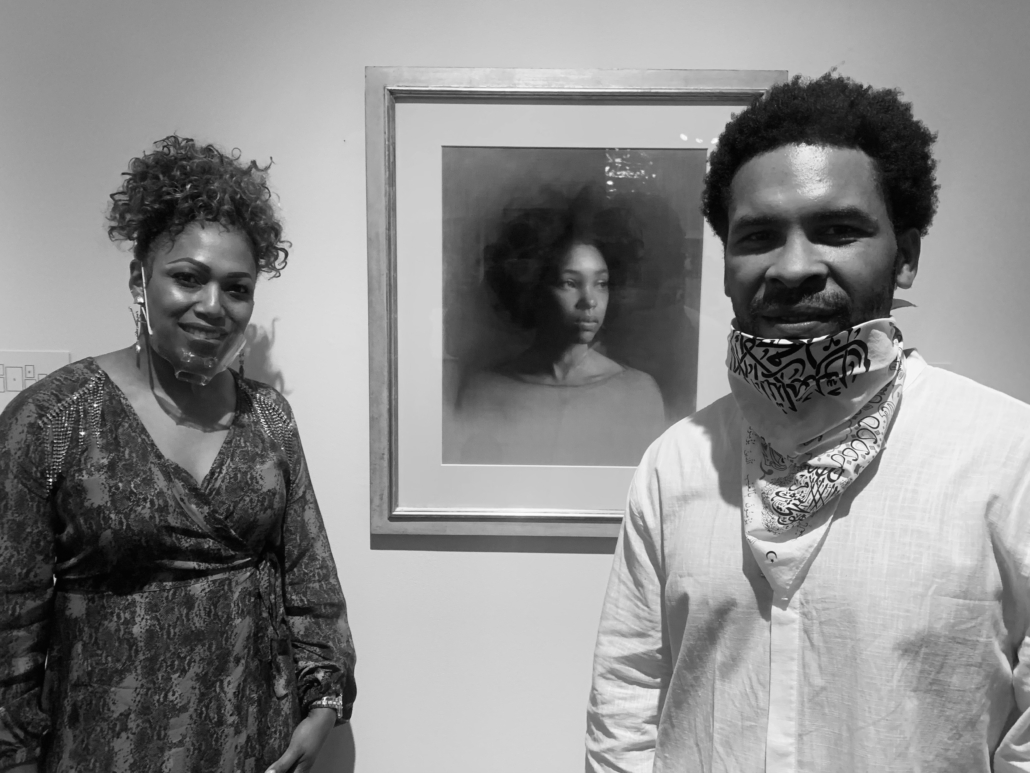

Quan Holt picked up wheelchair basketball after losing his left leg.

Remarkably, after less than a year, Holt was moving forward. With money from the significant settlement he received as a result of the accident, he and his wife purchased a house in a nice neighborhood and a new car. He joined a wheelchair basketball league and was being recruited for several college teams. After discovering the opioids and other medications he was sent home from the hospital with did little to lessen the excruciating pain from his injuries, he turned instead to the aid of marijuana.

That was a mistake. In Alabama, it is illegal to possess any amount of marijuana for any reason. But Holt, desperate for relief, didn’t ask the right questions or think through the potential risks when he obtained medical marijuana cards from Georgia and California. He learned the hard way when the Alabama Law Enforcement Agency (ALEA) arrested him at his Phenix City, Ala. house on July 16, 2020. By the time he got out of jail, ALEA had taken his car, his cash, his cell phone, and other belongings, using a process known as civil asset forfeiture which allows law enforcement to seize and even keep property they believe is connected to criminal activity. Despite Holt’s own admission that he used marijuana to manage pain, law enforcement charged him like a drug kingpin – a decision his attorney believes was made to strengthen the state’s case for keeping his property, not because of any evidence that Holt is a drug dealer.

In the space of two years, Holt lost his leg, his mobility, and his ability to support his family. Confused by ill-considered guidance from doctors who suggested he try marijuana and so desperate to manage his pain he failed to seriously consider the consequences, he also lost $60,000 worth of property he’d purchased with proceeds from the civil settlement from his catastrophic accident.

Now awaiting trial in the case that could result in a prison sentence, Holt is broke, depressed, frightened, and in pain.

The Cannabis Conundrum

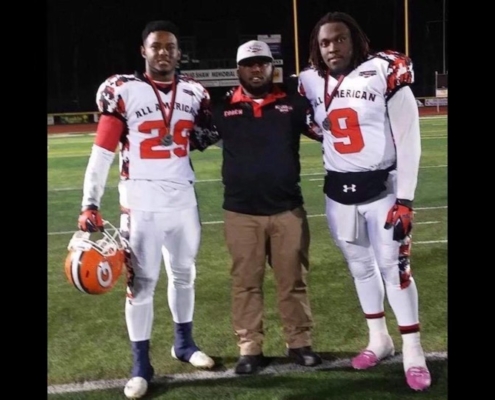

This was not the life Holt envisioned. In high school, he was a nationally ranked football player who left parties if there was any substance abuse, even drinking. “I grew up in the ghetto, in the projects. I knew football was my ticket out,” he told Alabama Appleseed.

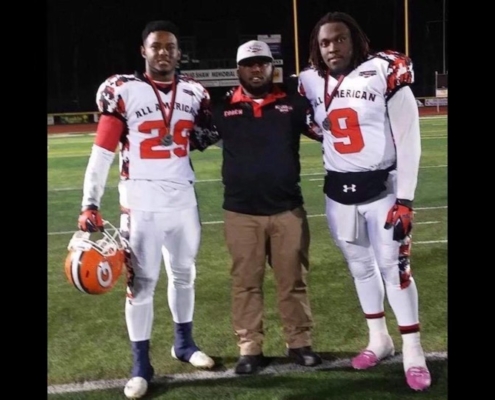

He earned a scholarship and played at a private high school in Phenix City, then went to Lindenwood University in Illinois. He took a break after his freshman year and considered joining the Marines. It was during this break, the fall of what would have been his sophomore year in college, that the accident happened.

Quan’s football talents earned him a scholarship to a private high school and to college. Here, he is Number 29.

Just before dawn on Nov. 19, 2018, Holt and his girlfriend happened upon a 61-year-old woman who had gotten a flat tire on a busy road in Columbus, Georgia. He was helping her move the vehicle to safety when he was struck by an 18-wheeler. Army medics who happened upon the scene on their way to Fort Benning saved his life – but they could not save his left leg, which was amputated above the knee. His right femur was broken, his pelvis fractured, his bladder ruptured, his liver lacerated, and his spine injured.

Holt told Appleseed he was placed in a medically induced coma for about a month and prescribed morphine to manage the pain. By the time he went home, his 5’11” frame had plummeted from 225 to 125 pounds.

Records show the hospital sent him home with 11 medications, including Fentanyl, a highly addictive synthetic opioid that the CDC cites as a major driver of overdose deaths. Holt says none of them controlled his pain. Neither did multiple follow-up surgeries. His worst pains were so-called “phantom pains,” his brain confused by signals from the nerves that were damaged when surgeons amputated his leg. He told Appleseed that one of his doctors recommended medical cannabis and referred him to the Georgia Department of Public Health and BePainFreeGlobal, a marijuana retailer based in California.

These were dangerous, ill-informed recommendations. Under Georgia law, a physician may recommend their patient be permitted to register for a Low THC Card. If the recommendation is approved – and it appears Holt’s was – the Georgia Department of Public Health provides a registry card allowing the patient to legally possess up to 20 fluid ounces of “low THC oil.”

Georgia’s law does not allow people to purchase most marijuana products. More importantly for Holt, Georgia’s law only applies in Georgia. A Georgia Low THC Card is meaningless in Alabama, where he lives. Phenix City, Ala., where Holt lives, is tied so closely to the larger Columbus, Ga. just across the state line that it is Alabama’s only municipality to operate in the Eastern Time Zone. Residents move constantly across state lines for work and commerce. Holt’s doctors were in Georgia and covered by Georgia law – but he was not.

The medical marijuana card issued by California physicians via BePainFreeGlobal’s affiliated network is even more troubling. On Oct. 19, 2020, Alabama Appleseed called BePainFreeGlobal and asked about having marijuana shipped to Alabama. The customer service representative confirmed they ship to all 50 states as long as the customer has a California doctor’s recommendation. He referred Appleseed to several California-based telehealth providers, noting that one in particular was cheap, quick, and “they approve everyone.”

Appleseed told him that marijuana, medical or otherwise, is not legal in Alabama. “I definitely understand what you’re saying,” the customer service representative said. But his employers, he said, “feel that they’re under some kind of legal umbrella due to like constitutional law and the Bill of Rights.” The representative then transferred Appleseed to “somebody more on the up end” of the management chain. A voicemail and attempts to follow up via email received no response.

BePainFreeGlobal may or may not be protected by “some kind of legal umbrella” – it seems doubtful – but Holt is out in the storm. Until and unless marijuana laws are made more uniform nationwide, there will always be people ensnared by the jurisdictional traps that mean what is perfectly legal in one state is a felony in another.

After losing his leg, Quan remained committed to supporting his children.

Helping his toddler walk, while learning to walk all over again himself.

Holt does seem to have been a heavy user. He was arrested with about three ounces of marijuana and various products. But there is no evidence that he sold marijuana or intended to; no evidence that he used his vehicle to distribute marijuana; and significant reason to believe that he, like his wife, possessed it solely for personal use. There is no weight threshold distinguishing marijuana possession “for personal use” from “for other than personal use” in Alabama law; that determination is made solely by charging authorities. Yet the difference in terms of outcome is enormous. Possession for personal use is a misdemeanor on the first arrest and a Class D felony all subsequence arrests. Possession for other than personal use is a Class C felony, carrying serious consequences. This was Holt’s first arrest for possession.

Out in the storm

The complaint filed in the civil asset forfeiture case says that a neighbor who was in law enforcement alerted ALEA of marijuana in Holt’s house, going so far as to trespass on Holt’s property to photograph his two marijuana plants. Holt was not living there at the time because he and his wife had separated. She remained in the house with their son, while Holt moved to a nearby apartment. Their relationship was strained, and at one point he insisted she move out of the house.

Based on the neighbor’s report, an ALEA agent came to the house, where Holt’s wife was packing up her clothes. Holt’s wife told him that the marijuana plants did not belong to her and that she knew they were illegal. According to the complaint, she asked if she could call and ask Holt to come over. Law enforcement vacated the driveway and concealed themselves, waiting for Holt to arrive.

Holt told Appleseed he came quickly, thinking he and his wife would be continuing their ongoing conversation about custody arrangements for their one-year-old son. Instead, he was greeted by weapons and handcuffs. “My car isn’t completely in my driveway [when] three undercover agents come out of my house with their guns drawn at me, and a state trooper pulled in behind me to block me from leaving,” he said.

The two marijuana plants and paraphernalia were already wrapped and bagged as evidence when he got inside. According to the complaint, police also found 90 grams of marijuana in his car, along with THC gummies, five packs of THC vape cartridges, and a bottle of THC oil in his car. They found four grams of marijuana and a THC vape in his wife’s car.

The Lee County District Attorney Pro Tem told Appleseed that at this stage, charging decisions are based on recommendations from law enforcement. She said she is unable to comment on the case beyond what is in the record, and suggested we call ALEA. ALEA did not respond to Appleseed’s request for its valuation of the marijuana, and said pending litigation meant it could not comment on our request for assistance in understanding the assertion by the law enforcement agency that the marijuana was for other than personal use. Holt’s lawyer says there are documents showing Holt paid less than $400 for the THC products from BePainFreeGlobal, and that the two plants were too immature to have produced any cannabis that could be used or sold, and therefore essentially valueless at the time of his arrest.

Police arrested both Holt and his wife and booked them into jail. Holt was charged with First Degree Possession of Marijuana for Other than Personal Use, a Class C felony; Unlawful Manufacture of a Controlled Substance, which can be a Class A or B felony, and Possession/Receipt of a Controlled Substance, a Class D felony. Bond for the three cases came to $54,500.

Holt’s wife was charged with Second Degree Possession of Marijuana, a misdemeanor, and Possession/Receipt of a Controlled Substance, a Class D felony. Her bond totaled $2,500.

Holt and his wife both bonded out within a few hours. By then, police had taken more than $9,000 in cash that he and his wife had withdrawn from their shared account during an acrimonious low point in their dispute, as well as the 2019 Dodge Charger and everything inside of it – including his iPhone, clothes he had recently purchased for his baby boy (who has since outgrown them), a new lawnmower battery he needed to replace one that had died, and the licensed firearms he kept to protect himself after his injury limited his mobility.

He has not seen any of it since.

Policing for Profit

Holt purchased his car and other items seized not from drug activity, but from proceeds from the settlement he received after being crushed by an 18-wheeler. While he acknowledges being a heavy marijuana user to manage his pain, no one gets rich from buying drugs.

Holt retained a lawyer to challenge the state’s seizure of his belongings. The state argues in its complaint that the car, cash, and firearms were “used, or intended for use,” in unlawful activity. But the ostensible purpose of civil asset forfeiture laws is to separate individuals who might be beyond the reach of the law (for instance, drug kingpins residing outside the U.S.) from their ill-gotten riches.

Quan Holt cares for his young children, despite having his car, cash, and other valuables seized by law enforcement.

And that is where Holt’s case becomes both interesting and terribly dismaying. Holt is decidedly not a drug kingpin. In an interview with Alabama Appleseed, the former high school football star admitted to spending tens of thousands of dollars on the products he needed to manage his pain from the 2018 accident. Much of that money went to BePainFreeGlobal.com, the California-based outfit that ships nationwide, seemingly with impunity, despite state and federal laws explicitly barring it from doing so. In fact, Holt’s attorney, Mike Segrest, told Appleseed he offered to share with ALEA receipts and other evidence of BePainFreeGlobal’s activity, which could potentially help law enforcement investigate the business. Segrest said ALEA responded to his offer by threatening to file federal charges against Holt for using the U.S. Postal Service to receive contraband.

The steep charges against Holt gave Alabama authorities leverage over more than his liberty. They also enabled law enforcement to seize his property under Alabama’s expansive civil asset forfeiture law, which allows the state to take and keep currency, vehicles, houses, land, weapons, and virtually any other item that is they believe is the proceeds of, or was used to facilitate, criminal activity.

Holt has not yet been indicted, so the outcome of the criminal charges against him is still unknown. Regardless, he is already suffering the consequences: he’s broke, he lost his car, and his untreated pain makes every moment agony.

He earns a little money from his job at the front desk of a doctor’s office, but between child support for his two children (a daughter from a prior relationship and a young son from the marriage that just ended), payments to his bail bondsman, and other expenses, it’s not enough. His doctor prescribed pain medication and a muscle relaxant, Holt said. But “my prescription has been sitting at the pharmacy for about a week because I do not have the funds to go and get it.”

But what of the other consequences? Should Holt lose his valuables because he was treating his pain with a type of medication that is legal in states where the overwhelming majority of Americans live?

Alabama says yes. In its complaint, the state says the items it seized: $9,306, the Dodge Challenger, and the firearms, were “used, or intended for use, in a transaction which would be in violation of the Alabama Controlled Substances Act or other laws of the State of Alabama concerning controlled substances and/or that said vehicle and weapon were used, or intended for use, to transport, or in any manner facilitate the transportation, manufacture, sale, receipt, possession, or concealment of a controlled substance or precursor to manufacture in violation of the Alabama Controlled Substances Act amended and/or is a traceable drug asset.”

Boiled down, that avalanche of law enforcement argot means the state is pretty sure all that stuff is somehow linked to a crime. According to Segrest, ALEA asserts that the mere fact that the Challenger had marijuana in it means the state is entitled to keep it.

Pursuant to that assertion, in its complaint, the state “respectfully request[s]” that, if the money is “condemned,” (that is, if a judge decides Holt should never get it back), 70 percent ($6,514.20) be given to the Alabama Law Enforcement Agency, 20 percent ($1,861.20) to the Lee County District Attorney’s Fund, and 10 percent ($930.60) to the Alabama Department of Forensic Science’s Auburn Lab.

It asks that the “monetary proceeds” of the Dodge Challenger – a sports car that cost Holt more than $40,000 off the lot – be divided the same way, and suggests the firearms be given to the Alabama Law Enforcement Agency for “general law enforcement purposes or destruction.”

Questionable Constitutionality

Quan Holt’s situation – police seizing property he acquired as a result of his kindness to a stranger nearly costing him his life – seems uniquely unjust. But it is just the latest in a long line of examples of law enforcement profiting wildly from civil asset forfeiture where the public safety benefits are tenuous at best.

In 2017, the Alabama Appleseed Center for Law & Justice and the Southern Poverty Law Center undertook an extensive review of Alabama civil forfeiture cases. We examined 1,110 cases in 14 counties, representing 1,591 civil asset forfeiture cases filed in Alabama in 2015.

In 55 percent of cases we examined where criminal charges were filed, the charges were related to marijuana. In 18 percent of cases where criminal charges were filed, the charge was simple possession of marijuana and/or paraphernalia – crimes that require the person to part with money or valuables in order to commit them.

Segrest, the lawyer who represents Holt in both the criminal and civil proceedings, is mounting a vigorous challenge to both. Among other things, he observes that Holt was not living at the residence when police served his wife with the search warrant – that in fact, he only came there because his wife messaged him and asked him to come and talk after law enforcement had already threatened her with arrest. The search and seizure of the car and its contents, he argues, was illegal.

Segrest makes another argument about the seizure’s constitutionality, one that goes to the heart of an evolving argument about limits of civil asset forfeiture and the use of financial penalties more broadly. Even if the search was legal, he says, the property seized cannot be forfeited because it is disproportionate to the crime committed.

Segrest’s argument is based on new constitutional law stemming from the 2013 case of Tyson Timbs, an Indiana resident who used life insurance money he received after his father died to buy a $42,000 Land Rover. Timbs, who was addicted to and occasionally sold opioids, also once used the Land Rover to travel to a location where he sold heroin to undercover officers. He was arrested on his way to another sale, and law enforcement seized the vehicle.

Timbs eventually pleaded guilty to one count of dealing a controlled substance and one count of conspiracy to commit theft. He fought the seizure of his vehicle, arguing that its value was more than four times the $10,000 maximum criminal fine available. The state of Indiana countered that the excessive fines clause of the U.S. Constitution does not apply to the states and also that civil asset forfeitures are not punitive, and that it was therefore entitled to keep the Land Rover.

Timbs v. Indiana made it all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In a unanimous ruling, the justices ordered Indiana to reconsider the case. Timbs eventually got his Land Rover back.

Segrest argues persuasively that Holt’s case is similar to Timbs. The financial penalties associated with the crimes Holt is accused of are steep: The manufacturing charge alone could carry a fine of up to $60,000. Segrest argues that “[t]he arresting officers inflated the charges against Mr. Holt to felonies … in order to justify the unlawful taking of property with a value of approximately $60,000.”

In other words, his hunch is that law enforcement deliberately over-charged Holt to build a case for the eventual forfeiture of his valuables. If true, that would mean they decided it was worth exposing a medically compromised father of two to a lengthy prison term because they wanted to keep his flashy car and his cash.

Given Alabama law enforcement’s track record of using civil asset forfeiture laws to seize things like acres of peach-growing land a Chilton County sheriff hoped to repurpose as a shooting range, it is not a stretch of the imagination to be skeptical of state state’s motives. Certainly, the Lee County District Attorney’s office that is pursuing the forfeiture deserves extra scrutiny: In Nov. 2020, a special grand jury indicted District Attorney Brandon Hughes for eight felonies, including violating the state ethics act, conspiring to commit first-degree theft, and first-degree perjury. The indictment alleges a myriad of ways Hughes used his office for personal gain. Among other things, he is alleged to have conspired to steal a pickup truck from a Chambers County business and to have added three of his children to the office payroll. Hughes was District Attorney at the time Holt was charged.

“The cycle continues every day” – For Holt, and for law enforcement agencies who profit from unproven crimes

Litigation is not the only way to protect Holt and other Alabamians, including the many individuals whose seized property is less than the cost of the lawyer they would need to get it back. In 2021, a bipartisan group of Alabama lawmakers introduced a bill that would end civil asset forfeiture in case like Holt’s.

SB 210 would end civil asset forfeiture in criminal drug offenses and replace it with a unified criminal process. It would also require most criminal forfeitures happen after proof of conviction, making it much harder to law enforcement to keep otherwise lawful property that wasn’t clearly shown to be the fruits or instrumentality of criminal activity.

The state could still take and keep contraband such as controlled substances or gambling machines, but it would have to prove to a judge’s satisfaction that any otherwise lawful property like vehicles, cash, or other valuables seized had something to do with criminal activity before it could keep them.

If passed, SB 210 would also extend access to counsel in criminal cases to any related forfeiture proceedings, meaning that people would no longer have to pay for a lawyer to recover their own property even if they were found not guilty or never even charged with a crime. It would expand opportunities for people like Holt to get their valuables back prior to their criminal conviction, including if the valuables are “not reasonably required to be held for evidentiary reasons.” And it would create a proportionality hearing enabling people like Holt to argue that even if their property were incidentally used in the commission of a crime, the harm caused by its forfeiture would be excessive.

Quan Holt is facing a possible prison sentence for possession of marijuana, a substance legal in states where more than half of Americans live.

Nor is forfeiture reform the only law that, if passed, could protect people like Holt. This session, the Alabama legislature will consider two bills with the potential to put Alabama’s marijuana policy more in line with the rest of America’s. The first, filed by Sen. Tim Melson (R-Florence), would legalize medical marijuana for treatment of about 20 conditions, including intractable pain. The second, filed by Sen. Bobby Singleton (D-Greensboro) would reclassify possession of small amounts of marijuana as a fine-only offense. In a state where Black people like Mr. Holt are four times as likely as their white peers to be arrested for possession of marijuana despite robust, longstanding evidence that the two groups use marijuana at roughly the same rate, marijuana policy reform of both types is a critical and long-overdue step.

For Holt – broke, depressed, in pain, still responsible for supporting himself and two children, and no longer in possession the vehicle he needs to get to and from work – all of these laws would have made a world of difference had they been passed prior to his neighbor’s decision to turn him in.

“It does feel like it’s overwhelming at times,” he said. “My mom comes and picks me up every morning to take me to work and she picks me up when I get off to bring me back to the house. And the cycle continues every day.”