By: Akiesha Anderson, Policy Director

This legislative session, Alabama Appleseed had four main legislative priorities: (1) Repeal or reform the Habitual Felony Offender Act; (2) Stop Civil Asset Forfeiture; (3) End Needless Driver’s License Suspensions; and (4) Create a Diversion Program Study Commission. Below is a summary of these priority issues that were deliberated by the 2021 Legislature.

The Habitual Felony Offender Act

Report: Condemned

Bills we supported: HB 107, HB 24

Legislation to repeal Alabama’s draconian Habitual Felony Offender Act (“HFOA”) is desperately needed. The HFOA currently ensnares hundreds of older people with life or life without parole sentences for offenses that would result in much shorter sentences under today’s laws. That is why we supported HB 107, sponsored by Rep. Chris England, designed to repeal the HFOA. This bill successfully made it out of the House Judiciary Committee with strong bi-partisan support, though it never reached the full chamber of the House of Origin for a vote. Appleseed thanks the 150+ Alabama judges, law professors, former prosecutors, and lawyers who signed on in support of a Dear Lawmaker letter and the countless constituents that sent emails or made phone calls urging legislators to support this important piece of legislation.

Legislation to repeal Alabama’s draconian Habitual Felony Offender Act (“HFOA”) is desperately needed. The HFOA currently ensnares hundreds of older people with life or life without parole sentences for offenses that would result in much shorter sentences under today’s laws. That is why we supported HB 107, sponsored by Rep. Chris England, designed to repeal the HFOA. This bill successfully made it out of the House Judiciary Committee with strong bi-partisan support, though it never reached the full chamber of the House of Origin for a vote. Appleseed thanks the 150+ Alabama judges, law professors, former prosecutors, and lawyers who signed on in support of a Dear Lawmaker letter and the countless constituents that sent emails or made phone calls urging legislators to support this important piece of legislation.

In addition to supporting a full repeal of the HFOA, Appleseed supported HB 24, a bill sponsored by Rep. Jim Hill, that was designed to reform the HFOA. If passed, this legislation would have allowed people who were sentenced under the HFOA for committing nonviolent offenses to petition the court for a review of their case and potentially be resentenced under current sentencing guidelines. We also supported an amendment to HB 24 that was offered by Sen. Arthur Orr that was designed to expand the class of people eligible for relief to include people who had “strikes” that led to an enhanced sentence arising from offenses that are now considered Class D felonies yet were Class C felonies at the time of initial sentencing. Although HB 24 came very close to passing out of both chambers, on the last day of session it failed to make it to the Senate floor for a full chamber vote.

Civil Asset Forfeiture

Report: Forfeiting Your Rights: How Alabama’s Profit-Driven Civil Asset Forfeiture Scheme Undercuts Due Process and Property Rights

Bills we supported: SB 210 (passed), HB 394

For too long, civil asset forfeiture has been improperly used as a revenue generator for law enforcement entities throughout the state. As currently structured, civil asset forfeiture empowers police to seize cash or other assets based on probable cause that they are connected in some way to certain criminal activity, even if no one is ever charged with a crime. We believe that this violates a host of due process rights and that civil asset forfeiture ought to be replaced with a system that ensures due process protections.

That is why, this session Alabama Appleseed supported SB 210 and HB 394, companion bills by Sen. Arthur Orr and Rep. Andrew Sorrell, that were designed to replace civil asset forfeiture with criminal asset forfeiture. We believe that as originally written, these bills would have been good for the State of Alabama due to them: (1) requiring transparency in the criminal asset forfeiture process; and (2) prohibiting Alabama law enforcement from receiving proceeds from individuals who have not been convicted of a crime.

Although SB 210 did ultimately pass, the substitute version that made it out of the State House was significantly diluted in comparison to the original version of the bill. While the bill that passed adds some minimal due process protections to existing civil asset forfeiture laws, Appleseed hopes that in the future, civil asset forfeiture is replaced altogether with criminal asset forfeiture.

Driver’s License Suspensions

Report: Stalled: How Alabama’s Destructive Practice of Suspending Drivers Licenses for Unpaid Traffic Debt Hurts People and Slows Economic Progress

Bills we supported: HJR 31 (passed), HB 129

At the beginning of this year, nearly 100,000 Alabamians had a suspended license for things unrelated to unsafe driving – namely failure to appear in court, failure to pay a traffic ticket, or an alcohol or drug offense (excluding DUIs). Suspending driver’s licenses for things unrelated to road safety hurts families by making breadwinners forego necessities; slows the economy by keeping people out of work; and leads people to commit crimes to pay off their tickets. That is why Alabama Appleseed worked closely on HJR 31 and HB 129, legislation sponsored by Rep. Chris Pringle and designed to end the practice of suspending driver’s licenses for frivolous reasons. Although HB 129 ultimately did not come up for a vote to pass out of the House Judiciary committee this session, HJR 31 which provides the mechanism for the State to opt out of requiring license suspensions for petty drug offenses successfully made it out of the Legislature and to the Governor’s desk.

Diversion Programs

Report: In Trouble: How the Promise of Diversion Clashes with the Reality of Poverty, Addiction, and Structural Racism in Alabama’s Justice System

Bills we supported: HB 71, HB 73

A goal of Alabama Appleseed is to increase access to alternatives to incarceration, and beyond-the-prison-walls public safety solutions. It is no secret that Alabama’s men’s prison system is currently in crisis. Our history of tough on crime laws have led to us having one of the highest incarceration rates in the world, the highest prison homicide rate in the nation, and a men’s prison system that is dangerously overcrowded. We are also in the process of being sued by the U.S. Department of Justice, as a lawsuit that was filed under the Trump Administration has argued that our prisons violate the constitutional rights of all men housed in them. Appleseed believes that it is time for State leaders to seriously invest in alternatives to incarceration such as pre-trial diversion and Community Corrections programs, as one of many solutions to the human rights crisis in state prisons.

Although diversion programs currently exist throughout most of the state, not all Alabamians have access to them. That is why we supported HB 73, sponsored by Rep. Jim Hill, that would have required every judicial circuit to establish a Community Corrections program. Although this bill made it out of the House of Origin and Senate Judiciary committee, it never made it to the Senate floor for a full chamber vote.

Despite the existence of diversion programs and drug courts throughout most of the State, they are all participant-funded. This means that the budget to run and operate these programs is derived from the pockets of the people who utilize the programs. So this year we also supported HB 71, sponsored by Rep. Jim Hill, because we believe in establishing universal eligibility and completion requirements to safeguard against the existing practice of the completion of diversion programs being determined by whether all fees have been paid. If passed, HB 71 would have created an Accountability Court Commission tasked with overseeing, studying, and creating uniformity amongst all existing diversion programs. Although this bill made it out of both the House Judiciary Committee and House Ways and Means Committee, it never made it to the floor of the House of Origin for a full chamber vote.

Other Legislation

In addition to the aforementioned central areas of focus, we also monitored, worked on, or supported several other key pieces of criminal justice reform legislation this session. Below is a summary of some of those other key pieces of legislation.

Criminal Justice – Prison Reform

Report: Death Traps

Bills we supported: HB 92, HB 106 (passed), HB 361

This session we also supported several pieces of legislation that we believed could have provided meaningful relief to Alabama’s current prison crisis. We were strongly in favor of bills such as HB 92, by Rep. Jim Hill, designed to create a second parole board; HB 106, by Rep. Chris England, designed to require the Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) submit to more legislative oversight; and HB 361, by Rep. David Faulkner, designed to require ADOC to assist people with getting a non-driver’s license identification card prior to release from prison.

While HB 92 made it out of the House Judiciary committee, it stalled when re-assigned to the House Ways and Means committee. Similarly, although HB 361 made it out of the House of Origin, it never made it on the agenda in the Senate Finance and Taxation General Fund committee. In contrast, HB 106 successfully made it out of both chambers and was sent to the Governor’s office for her signature.

Fines & Fees

Report: Under Pressure

Bills we supported: HB 499, SB 177

Stopping the State’s overreliance on court costs, fines, and fees was another area of legislative interest this session. That is why we supported companion bills HB 499, sponsored by Rep. Chris England and SB 177, sponsored by Sen. Roger Smitherman. If passed, these bills would have created an Alabama Court Cost Commission designed to review existing court costs to determine if they are reasonably related to the cost of running a court system. Unfortunately, although both bills made it out of the Judiciary committee in their respective House of Origin, neither of these bills received a vote by their full chamber. Thus, neither bill passed this session.

Criminal Justice – Drug Policy

Report: Alabama’s War on Marijuana

Bills we supported: SB 59 (passed), SB 149

It is time for Alabama to pass smart alternatives to criminalizing marijuana possession and use. That is why this session we supported SB 59, by Sen. Tim Melson that was designed to legalize medical marijuana. We also supported SB 149, by Sen. Bobby Singleton that was designed to decriminalize marijuana use and possession. Ultimately, SB 59 passed out of both chambers and was sent the Governor; and SB 149 passed out of the Senate Judiciary committee yet never made it to the floor of the House of Origin for a full chamber vote.

State Transparency

Bills we supported: HB 392 (passed), SB 165, SB 290

Alabama Appleseed strongly supports bills designed to strengthen government transparency in all regards. That is why this session we closely watched HB 392, sponsored by Rep. Mike Jones; SB 165, sponsored by Sen. Arthur Orr; and SB 290, sponsored by Sen. Greg Albritton. SB 165 was designed to strengthen Alabama’s existing open records law and both HB 392 and SB 290 were designed to increase checks-and-balance between the legislative and executive branch by requiring the executive branch to run multi-million dollar contracts and agreements past the legislature for legislative approval before such contracts could be finalized.

This session, SB 165 and SB 290 made it out of the Senate committees they were assigned to yet not to the floor of the House of Origin for a full chamber vote. In contrast, HB 392 made it out of both the House and Senate to the Governor’s desk. Unfortunately, however, the final version of HB 392 was significantly watered down before leaving the State House. The version of this bill sent to the Governor does not require legislative approval for the state to enter into large multi-million dollar contracts (as was the initial intent); rather, it simply requires legislative review of large contracts.

Juvenile Justice

Report: Hall Monitors with Handcuffs

Bills we supported: SB 203

Alabama’s public K-12 school children deserve due-process rights and protections against suspensions and expulsions. That is why we strongly supported SB 203, sponsored by Sen. Roger Smitherman and designed to create such due process protections. Although this bill made it out of the Senate Education committee and House or Origin, it failed to pass out of the House Education committee.

My name is Brenita Softley, and I am deeply honored to join Alabama Appleseed as a part-time extern. I am in awe of this organization’s mission to achieve justice and equity for all Alabamians— which are reasons that I decided to attend law school.

My name is Brenita Softley, and I am deeply honored to join Alabama Appleseed as a part-time extern. I am in awe of this organization’s mission to achieve justice and equity for all Alabamians— which are reasons that I decided to attend law school.

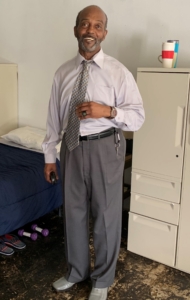

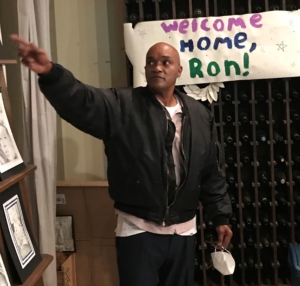

One year ago today, I walked out of Donaldson prison after being locked away for 37 years for a conviction received when I was a teenager. I was given a mandatory life without parole sentence in 1984. The criminal justice system in Alabama decided I was not worthy of ever living outside the prison walls. The system got it wrong, and every day I am living proof of that fact.

One year ago today, I walked out of Donaldson prison after being locked away for 37 years for a conviction received when I was a teenager. I was given a mandatory life without parole sentence in 1984. The criminal justice system in Alabama decided I was not worthy of ever living outside the prison walls. The system got it wrong, and every day I am living proof of that fact.